-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

Getting Started

In the beginning, there existed two deities known as Uranus and Gaia. They gave birth to the Titans (a race of powerful beings). Saturn, Titan of time, set reality in motion. Ultimately, time yielded the existence of the sky, the sea, and the end of life—death. To rule these notions, Saturn had three sons: Jupiter (sky), Neptune (sea), and Pluto (underworld). The son’s of Saturn were not Titans, but a race of seemingly less powerful deities known the world over as the Gods. Fearful that his sons would overthrow him, Saturn devoured them and imprisoned them in his stomach. This caused a great war between the Titans and Gods. Ultimately, the Gods won and Jupiter took the throne as leader of the Gods.

Jupiter |

Neptune |

Pluto |

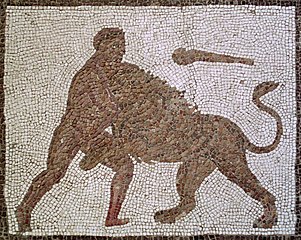

The examples in this section make extensive use of a toy graph distributed with Titan called The Graph of the Gods. This graph is diagrammed below. The abstract data model is known as a property graph and this particular instance describes the relationships between the beings and places of the Roman pantheon.

-

*key*: a graph indexed key. -

*key**: a graph indexed key that must have a unique value. -

+key+: a vertex-centric indexed key. - hollow head edge: a functional/unique edge (no duplicates).

- tail crossed edge: a unidirectional edge (can only traverse in one direction).

Unbeknownst to the Gods, there still lived one Titan. This Titan can not be seen, has no name, and is only apparent in the fact that reality exists. Upon the shoulders of this lost Titan, all of reality hangs together in an undulating web of relations.

Titan can be downloaded from the Downloads section of the project repository. Once retrieved and unpacked, a Gremlin terminal can be started. The Gremlin REPL (i.e. interactive shell) is distributed with Titan and differs slightly from the main Gremlin distribution in that is comes preloaded with Titan-specific imports and helper methods. In the example below, titan.zip is used, however, be sure to unzip the zip-file that was downloaded.

$ unzip titan.zip

Archive: titan.zip

creating: titan/

inflating: titan/pom.xml

creating: titan/src/

creating: titan/src/assembly/

...

$ cd titan

$ bin/gremlin.sh

\,,,/

(o o)

-----oOOo-(_)-oOOo-----

gremlin>The Gremlin terminal is a Groovy shell. Groovy is a superset of Java that has various shorthand notations that make interactive programming easier. The basic examples below demonstrate handling numbers, strings, and maps.

gremlin> 100-10

==>90

gremlin> "Titan:" + " The Rise of Big Graph Data"

==>Titan: The Rise of Big Graph Data

gremlin> [name:'aurelius',vocation:['philosopher','emperor']]

==>name=aurelius

==>vocation=[philosopher, emperor]

Gremlin is a graph traversal language that can be used with any Blueprints enabled graph database. The example below will load The Graph of the Gods into Titan. TitanFactory provides methods to create various Titan instances (e.g. local, distributed, etc.). A local, single machine instance of Titan is created using the TitanFactory.open(String directory) method. For the sake of understanding graphs, local mode is sufficient. Other pages in the documentation demonstrate distributing Titan across multiple machines, for instance using Cassandra or using HBase. Refer to the storage backend overview on how to choose the optimal persistence mode.

gremlin> g = GraphOfTheGodsFactory.create('/tmp/titan')

==>titangraph[local:/tmp/titan]GraphOfTheGodsFactory.create() is provided with titan-core and loads The Graph of the Gods dataset into a local TitanGraph. The method does the following to the graph newly constructed graph prior to returning it:

- Generate a collection of global and vertex-centric indices on the graph.

- Adds all the vertices to the graph along with their properties.

- Adds all the edges to the graph along with their properties.

A typical pattern for accessing data in a graph database is to first locate the entry point into the graph using a graph index and then, traverse from those elements to other elements in the graph via the explicit graph structure.

A unique, graph indexed key is denoted by a bold (graph index) and a star (unique) in The Graph of the Gods diagram above. Given that there is a unique index on name property, the Saturn vertex can be retrieved. The property map (i.e. the key/value pairs of Saturn) can then be examined. As demonstrated, the Saturn vertex has a name of “saturn” and a type of “titan.” Finally, the grandchild of Saturn can be retrieved with a traversal that expresses: “Who is Saturns’ childs’ child?” (the inverse of “father” is “child”). The result is Hercules.

gremlin> saturn = g.V('name','saturn').next()

==>v[20]

gremlin> saturn.map()

==>name=saturn

==>type=titan

gremlin> saturn.in('father').in('father').name

==>herculesThe property place is also in a graph index. This means it is possible to query the graph for all events that have happened within 50 kilometers of Athens (lat:37.97, long:23.72). Then, given that information, which vertices were involved in the event.

gremlin> g.query().has('place',Geo.WITHIN,Geoshape.circle(37.97,23.72,50)).edges()

==>e[2T-o-2F0LaTPQBM][24-battled->40]

==>e[2R-o-2F0LaTPQBM][24-battled->36]

gremlin> g.query().has('place',Geo.WITHIN,Geoshape.circle(37.97,23.72,50)).edges().collect { it.bothV.name.next(2) }

==>[hercules, hydra]

==>[hercules, nemean]Hercules, son of Jupiter and Alcmene, bore super human strength. Hercules was a demigod because his father was a god and his mother was a human. Juno, wife of Jupiter, was furious with Jupiter’s infidelity. In revenge, she blinded Hercules with temporary insanity and caused him to kill his wife and children. To atone for the slaying, Hercules was ordered by the Oracle of Delphi to serve Eurystheus. Eurystheus appointed Hercules to 12 labors.

Nemean |

Hydra Hydra

|

Cerberus |

In the previous section, it was demonstrated that Saturns’ grandchild was Hercules. This can be expressed using a loop. In essence, Hercules is the vertex that is 2-steps away from Saturn along the in('father') path.

gremlin> hercules = saturn.in('father').loop(1){it.loops < 3}.next()

==>v[24]Hercules is a demigod. To prove that Hercules is half human and half god, his parent’s origins must be examined. It is possible to traverse from the Hercules vertex to his mother and father. Finally, it is possible to determine the type of each of them — yielding “god” and “human.”

gremlin> hercules.out('father','mother')

==>v[16]

==>v[44]

gremlin> hercules.out('father','mother').name

==>jupiter

==>alcmene

gremlin> hercules.out('father','mother').type

==>god

==>human

gremlin> hercules.type

==>demigodThe examples thus far have been with respect to the genetic lines of the various actors in the Roman pantheon. However, the property graph data model is expressive enough to represent multiple types of things and relationships. In this way, The Graph of the Gods can also identify Hercules’ various heroic exploits - his famous 12 labors.

gremlin> hercules.out('battled')

==>v[40]

==>v[12]

==>v[48]

gremlin> hercules.out('battled').map

==>{name=nemean, type=monster}

==>{name=hydra, type=monster}

==>{name=cerberus, type=monster}

gremlin> hercules.outE('battled').has('time',T.gt,1).inV.name

==>cerberus

==>hydraBecause time is a vertex-centric index, retrieving edges incident to Hercules according to a filter on time is faster (typically O(log n), where n is the number incident edges) than doing a linear scan of all edges and filtering.

In the depths of Tartarus lives Pluto. His relationship with Hercules was strained by the fact that Hercules battled his pet, Cerberus. However, Hercules is his nephew — how should he make Hercules pay for his insolence?

The Gremlin traversals below provide more examples over The Graph of the Gods. The explanation of each traversal is provided in the prior line as a // comment.

gremlin> pluto = g.V('name','pluto').next()

==>v[4]

gremlin> // who are pluto's cohabitants?

gremlin> pluto.out('lives').in('lives').name

==>cerberus

==>pluto

gremlin> // pluto can't be his own cohabitant

gremlin> pluto.out('lives').in('lives').except([pluto]).name

==>cerberusgremlin> // where do pluto's brothers live?

gremlin> pluto.out('brother').out('lives').name

==>sky

==>sea

gremlin> // which brother lives in which place?

gremlin> pluto.out('brother').as('god').out('lives').as('place').select

==>[god:v[16], place:v[36]]

==>[god:v[8], place:v[32]]

gremlin> // what is the name of the brother and the name of the place?

gremlin> pluto.out('brother').as('god').out('lives').as('place').select{it.name}

==>[god:jupiter, place:sky]

==>[god:neptune, place:sea]This section presented some basic examples of how to create a local Titan instance, load it with data represented in GraphML, and traverse that data using Gremlin. In essence, a graph database is all about representing some world model (structure) and traversing it to solve problems (process).

The remainder of this documentation discusses more in-depth examples and configurations for using Titan. Specifically,

- Learn more about Titan's core interface

- Read about choosing a Titan storage backend