-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1.2k

Conflict Resolution with Guns

The conflict resolution algorithm (also called HAM) is at the center of everything gun does. It's how peers eventually arrive at the same state, and how offline edits are merged. Every change in the system goes through HAM.

Before reading this, we recommend you read through this tech talk, which explains the high level concepts in easy to understand terms. Also, check out the primer on our CAP Theorem tradeoffs.

Finally, for those of you who know of Kyle Kingsbury (Aphyr), here are some good tweets about us from him. We are building out Jepsen tests with PANIC, our distributed testing framework.

These are the constraints HAM operates under.

Favor high-availability over strong consistency, allowing users to make edits even when the machine is entirely offline (like a cellphone user without a network connection). This immediately rules out group consensus algorithms like Paxos or Raft.

The same state should be reached regardless of what order updates arrive in (update commutativity).

When merge conflicts happen, every machine should independently choose the same value (Strong Eventual Consistency).

Ultimately, we want to accept an update and merge it into our own data. Since gun's data structure is graph-oriented, updates will be in graph-format.

Because graphs only contain nodes, and nodes only contain key-value pairs, if we know how to merge key-value pairs, we can merge nodes, and in turn we can merge graphs. This means we'll focus on merging key-value pairs.

A key-value pair is atomic to HAM, meaning it won't try to merge primitives together, it'll just choose which to keep. Choosing is the tricky part, and requires an extra bit of metadata, called state. State is used to determine ordering of updates, and is always relative to the machine which receives it (including the machine creating the update).

Let's consider an example:

We have a node with one property, "name", a value of "Alice", and a state of 10.

{

"name": {

"value": "Alice",

"state": 10

}

}We get an update that lists "alice" as "Allison" and state as 8. Since the update state is less than our current state, we list it as only historically important, and don't include it in our data.

Unless you're using a journaling plugin, historical updates are ignored.

There's a bit more nuance to updates with greater state, so we'll discuss that in a bit. The next obvious question is what happens when we get an update with the same state as us, but with a conflicting value?

Well, according to the goals we listed, it doesn't matter what value we choose, so long as everyone chooses it. We just need to be consistent. Another advantage is that gun supports a subset of JSON, so we only need to handle conflicts in that subset.

This allows us to define some simple rules that guarantee convergence, mostly through type and lexical comparisons. Here is a layman explanation, followed by more details:

NOTE: Lexical sort is only used if there is a conflict on the exact same value at the exact same time.

Then there's no conflict, it doesn't matter which you choose.

Compare their string values with JSON.stringify, choosing the greater of the two.

This is dangerous territory, and if handled wrong can expose crippling application vulnerabilities. For example, a devious user submits an update with a state of 10 zillion. Now, no one gets to write until their state reaches 10 zillion plus 1.

That's generally frowned on. Check out this layman explainer:

HAM handles this with machine relative vector. When the "10 zillion" update comes in, HAM simply waits until your machine reaches the state of 10 zillion before acknowledging it's existence. If an update isn't acknowledged, it never escapes volatile memory onto disk. We call this a deferred update.

This is good, because if no other machines have reached that state, the attacker will have no advantage over any other machine in the system. Their update intentionally remains volatile, giving the attacker only two options - retry with a non-malicious state that is closer to other machines, or bare the responsibility of keeping the update safe themselves until other machines catch up.

It turns out this vector can be calculated for any linear value. Numbers, decimals, alphabets, or even with timestamps - which should sound scary. Timestamps are dangerous, since:

- System time doesn't always move forward (NTP corrections).

- Clock synchronization isn't always reliable.

- Some clocks move faster than others.

- Your system time might be off by any amount (especially when considering user meddling).

One of the constraints with HAM is that synchronization algorithms should not be required, including NTP and it's variants, so accurate clocks can never be assumed.

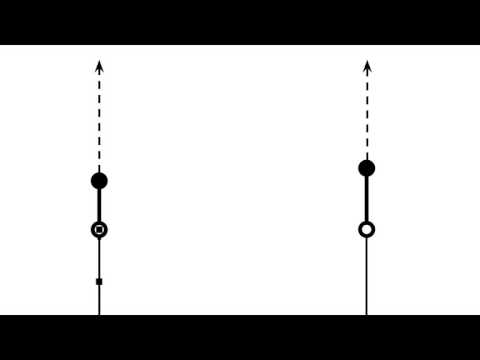

Luckily, HAM doesn't care if your clock is accurate. It only cares about machine relative ordering, and whether an update should be part of history, current state, or ignored until some point in the future. For a layman explanation of this, check this video out:

Each value is compared to the state of the last update and the state of your device's current loose clock.

Back to our username example:

{

"name": {

"value": "Alice",

"state": 10

}

}Say your system clock is at state 15.

We're using smaller numbers than

Date.now()because they're easier to mentally compare and reason about, but they have the same mathematical properties.

Any update with a state less than the last update (10) is considered stale and no longer relevant - if wanted, it can be journaled.

// This update is too old.

var update = {

name: {

value: "Allison",

state: 8,

},

}Any update with state greater than the last update (10), yet less than your process state (15) is immediately merged. The state of the last update now becomes what we just merged to (12).

// Sweet spot!

// This will be merged.

var update = {

name: {

value: "Alicia",

state: 12,

},

}Any update with a state greater than your system clock (15) is considered deferred, and won't be processed until your clock reaches that point. The further it is into the future, the larger vector it has in terms of distance before being processed.

// Nope, ignore this until the

// clock reaches state `22`.

var update = {

name: {

value: "Ally",

state: 22,

},

}Merging two nodes can be done by iterating over each field of an update, and deciding which field to choose: the one you already have, or the one proposed by the update.

If an update node has a field that the source object doesn't, the source node's field state is assumed to be -Infinity, meaning you always add that new field.

The same process can be repeated for graphs, iterating over each node in an update graph and merging it with the source.

You can find the HAM implementation in gun.js under the name function HAM.

HAM doesn't guarantee multi-process linearizability because in highly-available systems, you don't know when all updates have finished network propagation. Instead, it guarantees Strong Eventual Consistency (SEC). If linearizability is necessary, either use a consensus system like Paxos (sacrificing availability), or explicitly build it into your data using linked lists, directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), or others.

- No Strong Consistency, linearizability, or serializability.

- Vulnerable to the Double Spending problem.

If you want more information about how the conflict engine works, you can message us on Gitter or post a question on Stack Overflow with the #gun tag.

- Where gun stands on the CAP theorem.

- Some challenges to distributed operations.

- Why banks are not ACID.

- Concerns about timestamps (Aphyr).

- Eventual Consistency vs Strong Eventual Consistency vs Strong Consistency.

Again, we strongly recommend you check out the tech talk.