-

The

masterbranch of this repo is write-protected. All changes need to be made through Pull Requests. -

Pull requests must follow this following guidelines:

-

Have a linear history.

-

Only feature signed commits.

-

Be approved by at least one Code Owner.

Whatever you do, don't commit binary files. The .gitignore is already set up such that you can't commit most common binary files such as .aar, .apk, .so etc. but you should be aware that if it's binary, it doesn't belong in git version tracking.

Git LFS is a system to allow tracking of binary files, but great powers come with great responsibilities and it does more harm than good in most cases. To see if the repo contains any Git LFS files that may harm your build process, simply run the following from within the repo and look for matches:

grep -rnw . -e 'git-lfs'

If anything comes up, remove the corresponding files, rollback to a previous version without those, burn the repo down, but don't push that or we'll all be forced to use git lfs for the rest of eternity.

If you've got issues with your dev env, try asking other devs that work in the same environment. Asking someone with a different environment will only slow everyone down as they'll have to learn the specifics of your setup when they don't need to know.

I personally use a combination of JetBrain's PyCharm and Vim on macOs.

When you have to make changes for your environment specifically, don't commit those changes. You can add those files to a file called .git/info/exclude which acts like a local version of a .gitignore.

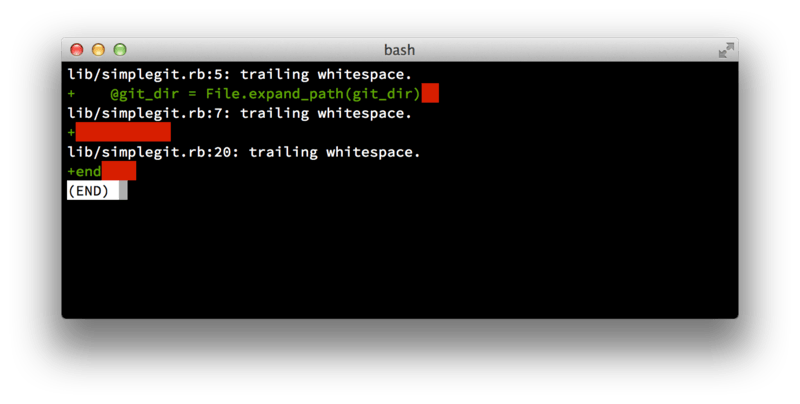

First, your submissions should not contain any whitespace errors. Git provides an easy way to check for this — before you commit, run git diff --check, which identifies possible whitespace errors and lists them for you.

If you run that command before committing, you can tell if you’re about to commit whitespace issues that may annoy other developers.

Try to make each commit a logically separate changeset. If you can, try to make your changes digestible — don’t code for a whole weekend on five different issues and then submit them all as one massive commit on Monday. Even if you don’t commit during the weekend, use the staging area on Monday to split your work into at least one commit per issue, with a useful message per commit.

If some of the changes modify the same file, try to use git add --patch to partially stage files (covered in detail in Interactive Staging).

If you want to remove a file from stating, run git reset HEAD {file}. This won't change the file content, don't worry.

The project snapshot at the tip of the branch is identical whether you do one commit or five, as long as all the changes are added at some point, so try to make things easier on your fellow developers when they have to review your changes.

Rewriting History describes a number of useful Git tricks for rewriting history and interactively staging files — use these tools to help craft a clean and understandable history before sending the work to someone else.

As a general rule, your messages should start with a single line that’s no more than about 50 characters and that describes the changeset concisely, followed by a blank line, followed by a more detailed explanation.

The Git project requires that the more detailed explanation include your motivation for the change and contrast its implementation with previous behavior — this is a good guideline to follow.

Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug" or "Fixes bug.". You messages should always start with an actionnable verb: Make, Fix, Add, Improve, Update, etc. Here is a template you can follow, which we’ve lightly adapted from one originally written by Tim Pope:

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary

More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72 characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit the body entirely); tools like rebase will confuse you if you run the two together.

Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug" or "Fixes bug." This convention matches up with commit messages generated by commands like git merge and git revert.

Further paragraphs come after blank lines.

Bullet points are okay, too

Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, followed by a single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here

Use a hanging indent

Try running git log --no-merges there to see what a nicely-formatted project-commit history looks like.

Change the pull request's name to something meaningful. By default it'll just be generated from the branch's name, but rename it yourself before posting it.

Use markdown titles to explain the changes you've made, and why you made them. This should include details about any contingency you've encountered while developing this feature, and links to resouces that helped you solve them, such as Stack Overflow links from any code snippet, page explaining the technology, documentation hinting at problematic limitations.

If that web page is huge (like one page documentation for the whole lib), then try to make those point to a specific point in the webpage you're linking. This can be done easily by clicking on little HTML anchors, typically next to the section titles. They should add a # at the end of the URL followed by the section title, like https://mydoc.com/doc/superlibrary.html#relevant-section-title.

If you PR is related to anything visual, add a screenshot of what the feature looks like. If it's dynamic, you can add a GIF instead, but it's not mandatory.

If you PR fixes a bug, describe precisely how the changes you've made affect the code behaviour.

Questions you should answers typically look like:

- Does this method now returns a

nullwhen the URL value is empty ? - Does that default parameter value changed somehow ?

If you've made any change affecting the public interface of a class or function (think Java's public methods), then document it.

Tests are tests, and tests can break. Before you push any commit to remote, make sure your branch is clean with git status, then checkout the base of your branch using git checkout {hash} and replace {hash} with you branch's base commit, then run all the unit tests there and see if they pass.

If they don't pass, then fix your dev environment (env vars and such), it's the only possible cause.

After you've made sure your environment is correctly configured, checkout your branch's latest commit and rerun all the unit tests you've just ran. If they don't pass, it means you've broke something in between and you should fix that before pushing.

Then, run a code coverage tool to make sure all the new code you've written is at the very least checked out by one test.

100% coverage is not enough !

You can have 100% coverage with poorly designed tests, unit tests should test many different scenario, not just one. But even with just one, you'll get that coverage, so it can be a misleading metric. A metric cease to be good when it becomes a target.

When trying to understand the codebase, you might be inclined to put print commands here and there. It's fine to do so, just use any tool you're confortable with, but please for god's sake don't let them in when commiting.

Before commiting, run a git status and see what file have changed. Only relevant files should have changed, if any odd file changed, run git diff {file} to see what you changed and if it's relevant. If it's not, then run git checkout -- {file} to reset it to the latest commited state.

This does not only apply to prints, but also newlines left after removing prints manually, automatic formatting tools in IDE that change the whole file to your own style settings etc. You should only perform the minimal changes to implement your feature.

The reason for that is that when reviewing your PR, reviewers might have a thousand files to "view" even though you just added a newline to them. Also, you'll appear as though you've made changes to a thousand file whereas you only meant to change two of them.

Document how to reproduce the issue, starting from git clone the affected pushed commit. Make sure to dump you $PATH variable as this tends to be affecting environment specific behaviour. When using Python, add your interpreter's pip3 freeze to list packets and their version. If the list is too long, put it inside a spoiler in markdown.

Tag your issue.

If you have any gut intuition as to what's causing it, write that down in the issue, along with any reference that might have helped you arrive at this conclusion.

- Contibuting to a Project on GIT

- Please follow our code of conduct.