Hey, welcome to the course, and thanks for learning Go. I hope this course provides a great learning experience.

This course is also available on my website as well as on Educative.io

- Welcome to the course

- What is Go?

- Why learn Go?

- Installation and Setup

- Hello World

- Variables and Data Types

- String Formatting

- Flow Control

- Functions

- Modules

- Workspaces

- Packages

- Useful Commands

- Build

- Pointers

- Structs

- Methods

- Arrays and Slices

- Maps

- Interfaces

- Errors

- Panic and Recover

- Testing

- Generics

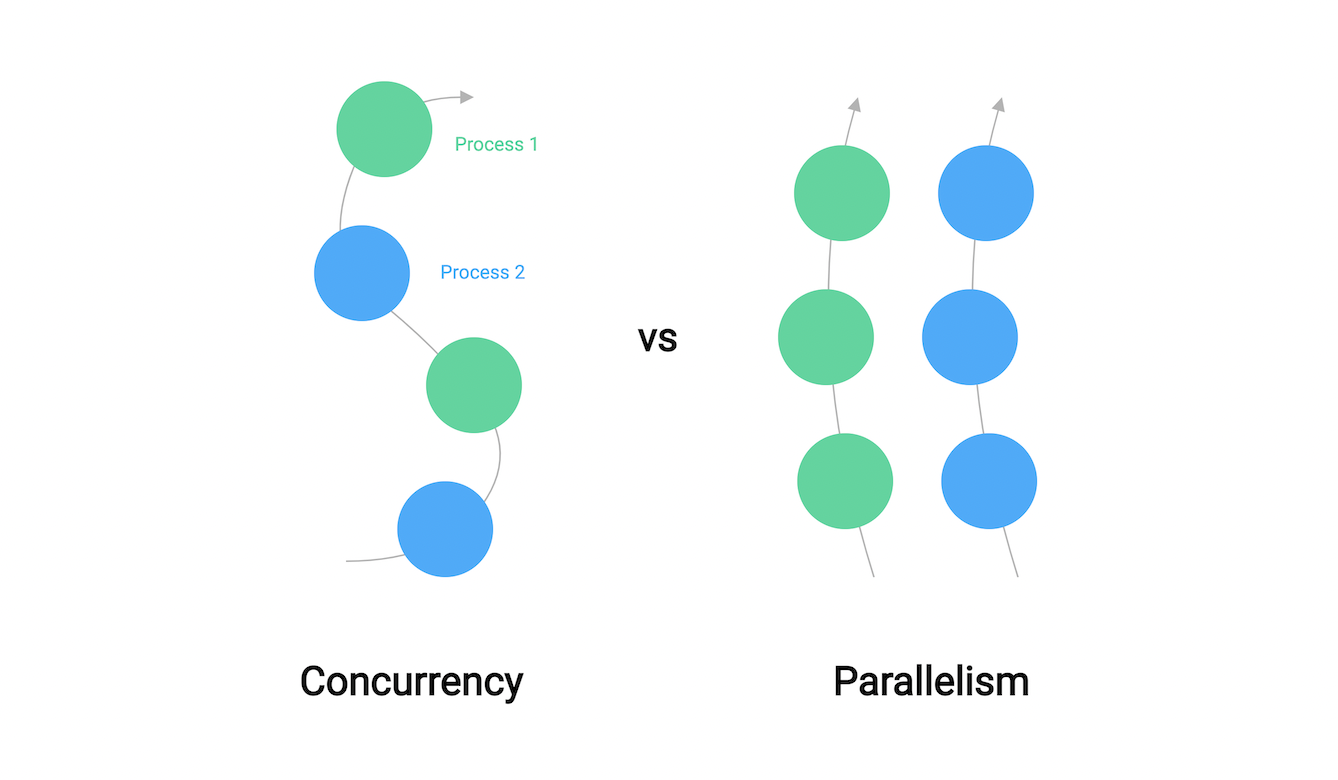

- Concurrency

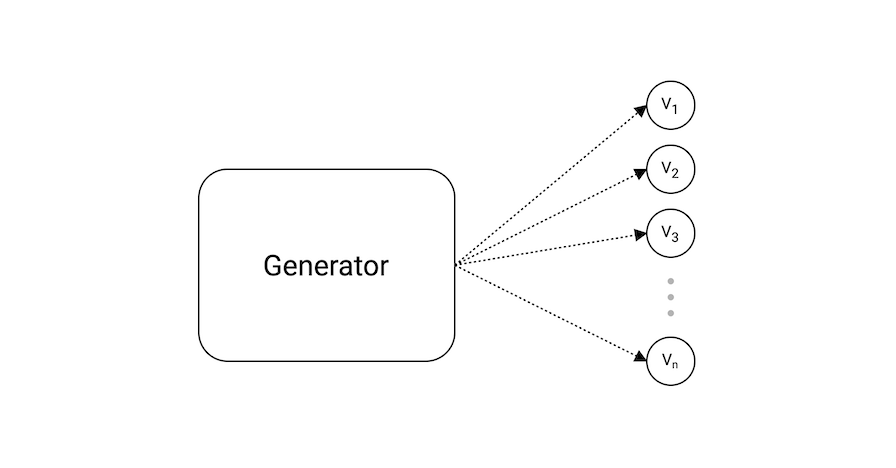

- Goroutines

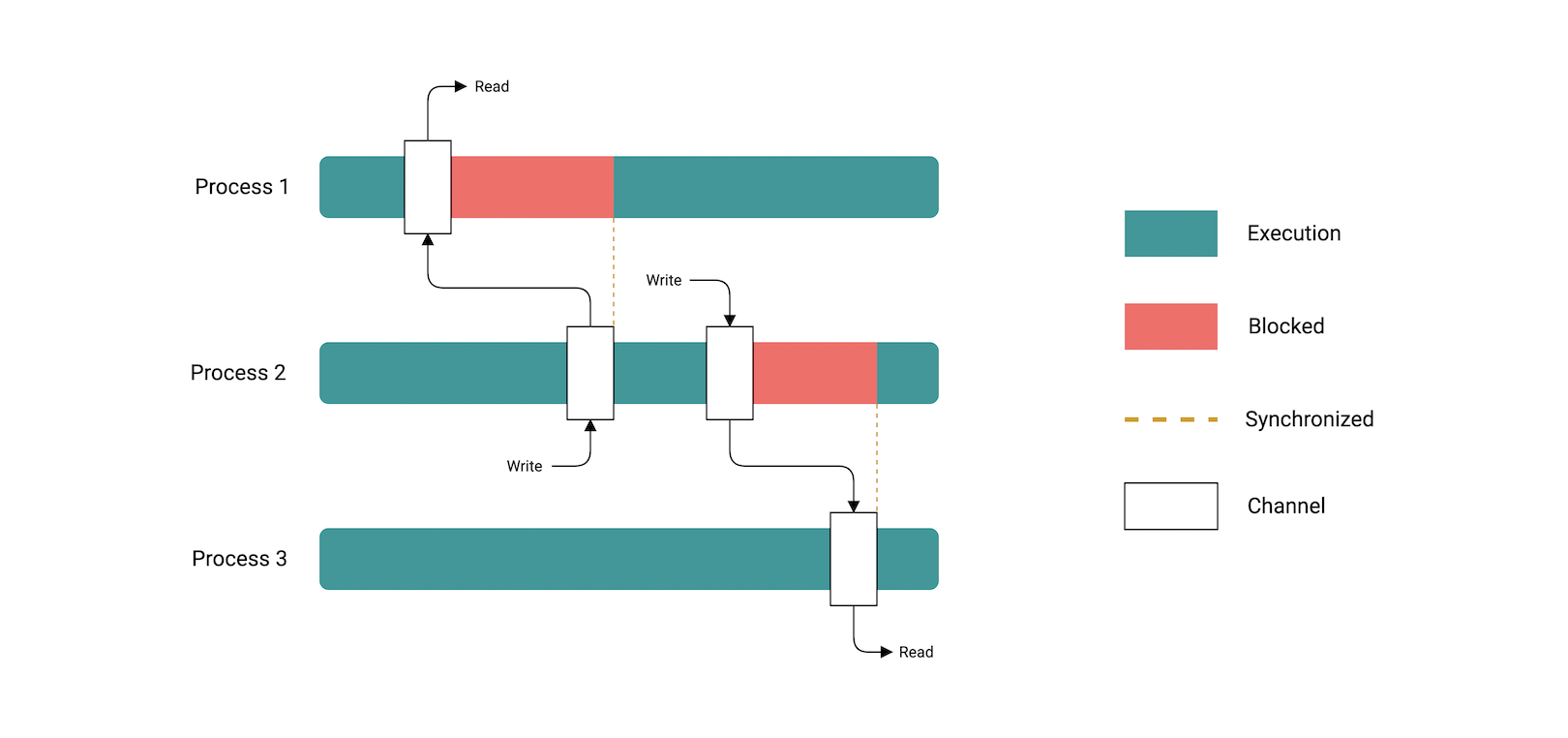

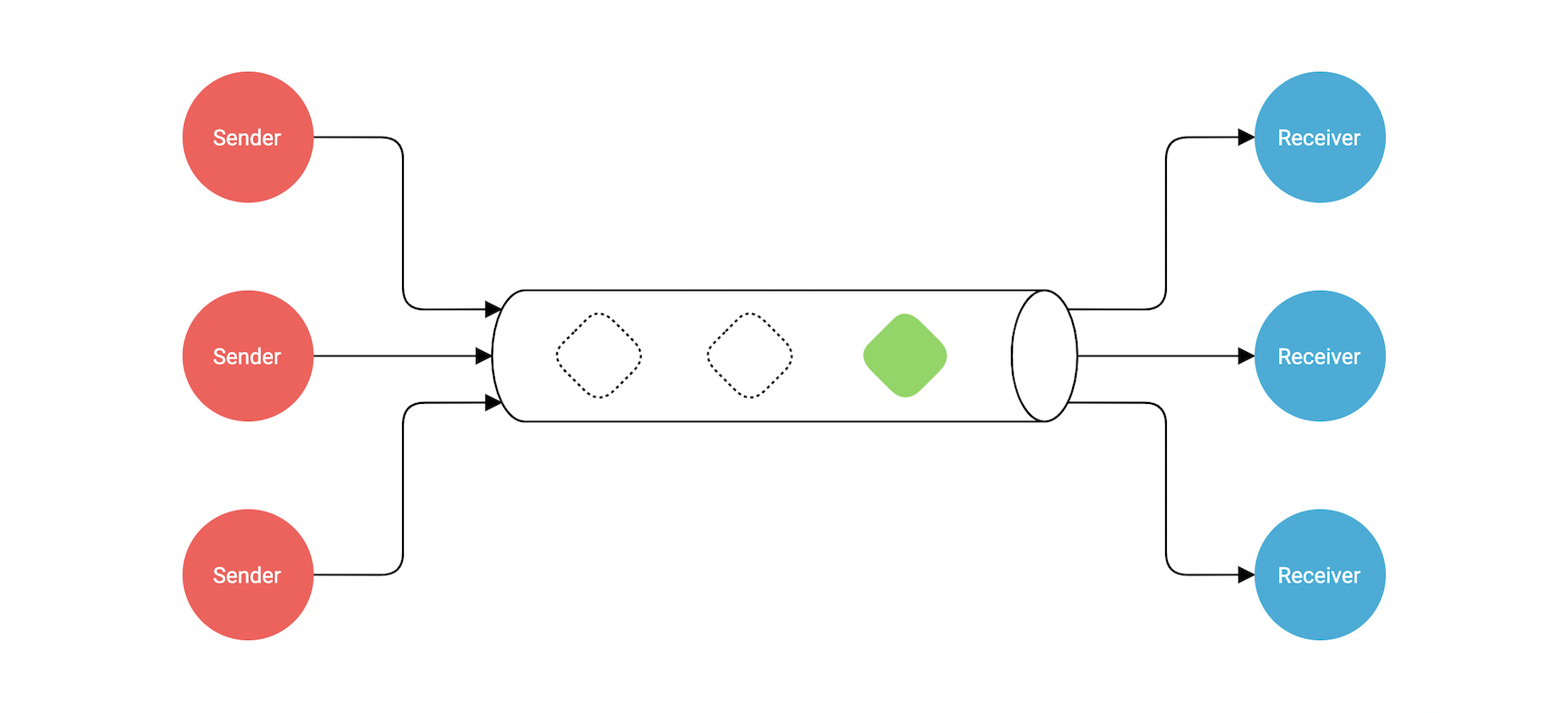

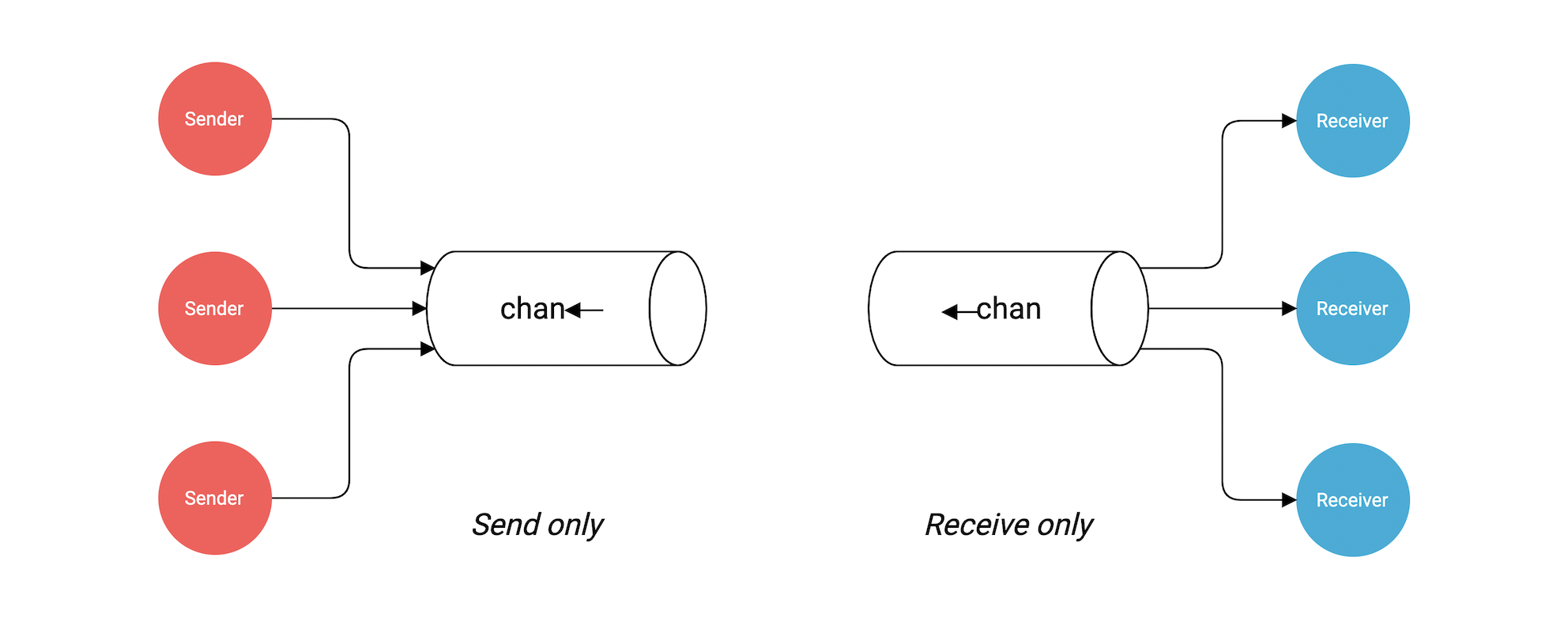

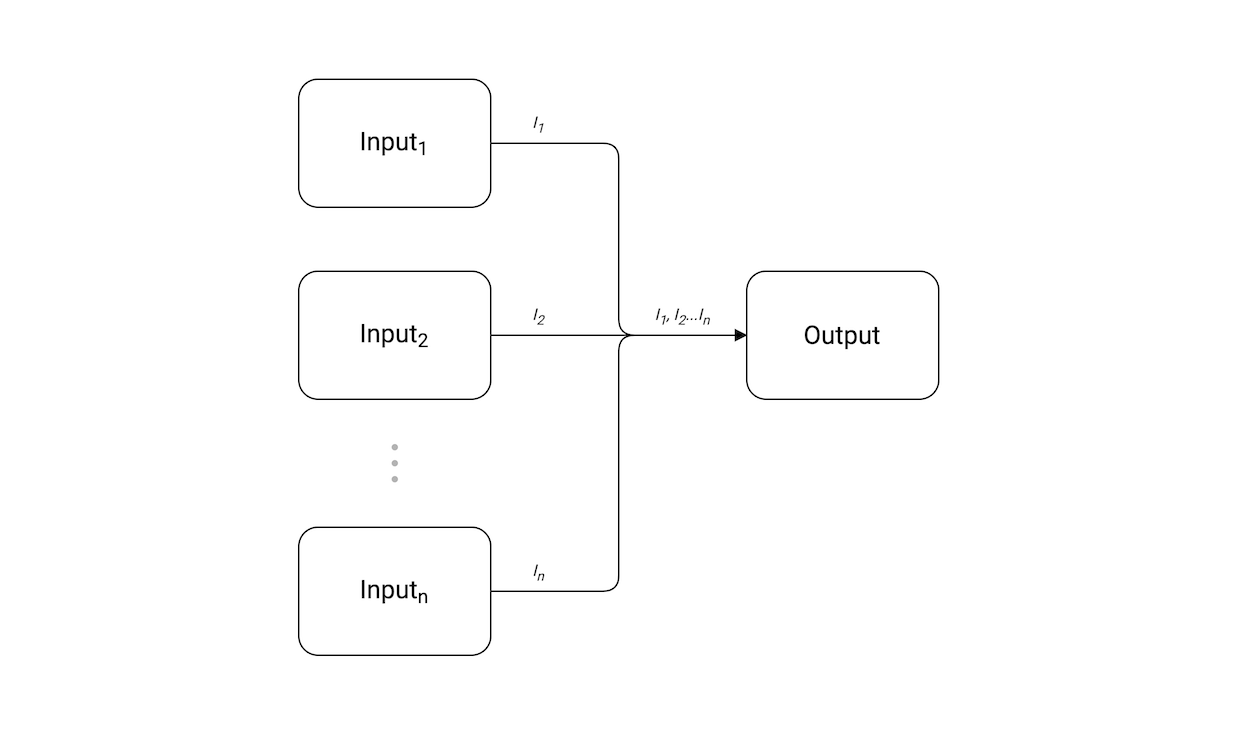

- Channels

- Select

- Sync Package

- Advanced Concurrency Patterns

- Context

- Next Steps

- References

Go (also known as Golang) is a programming language developed at Google in 2007 and open-sourced in 2009.

It focuses on simplicity, reliability, and efficiency. It was designed to combine the efficacy, speed, and safety of a statically typed and compiled language with the ease of programming of a dynamic language to make programming more fun again.

In a way, they wanted to combine the best parts of Python and C++ so that they can build reliable systems that can take advantage of multi-core processors.

Before we start this course, let us talk about why we should learn Go.

Go is quite easy to learn and has a supportive and active community.

And being a multipurpose language you can use it for things like backend development, cloud computing, and more recently, data science.

Which makes it highly suitable for distributed systems. Projects such as Kubernetes and Docker are written in Go.

Go has just 25 keywords which makes it easy to read, write and maintain. The language itself is concise.

But don't be fooled by the simplicity, Go has several powerful features that we will later learn in the course.

Go is growing fast and is being adopted by companies of any size. and with that, comes new high-paying job opportunities.

I hope this made you excited about Go. Let's start this course.

In this tutorial, we will install Go and setup our code editor.

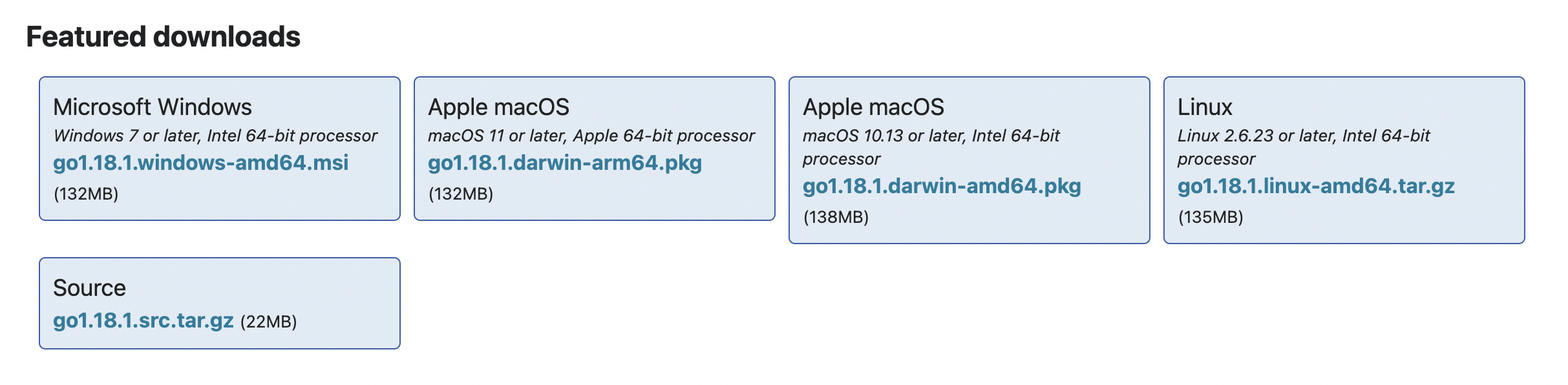

We can install Go from the downloads section.

These instructions are from the official website

-

Open the package file you downloaded and follow the prompts to install Go. The package installs the Go distribution to

/usr/local/go. The package should put the/usr/local/go/bindirectory in yourPATHenvironment variable. You may need to restart any open Terminal sessions for the change to take effect. -

Verify that you've installed Go by opening a command prompt and typing the following command:

$ go version

- Confirm that the command prints the installed version of Go.

- Remove any previous Go installation by deleting the

/usr/local/gofolder (if it exists), then extract the archive you just downloaded into/usr/local, creating a fresh Go tree in/usr/local/go:

$ rm -rf /usr/local/go && tar -C /usr/local -xzf go1.18.1.linux-amd64.tar.gz

(You may need to run the command as root or through sudo)

Do not untar the archive into an existing /usr/local/go tree. This is known to produce broken Go installations.

- Add

/usr/local/go/binto the PATH environment variable. You can do this by adding the following line to your$HOME/.profileor/etc/profile(for a system-wide installation):

export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/go/bin

Note: Changes made to a profile file may not apply until the next time you log into your computer. To apply the changes immediately, just run the shell commands directly or execute them from the profile using a command such as source $HOME/.profile.

- Verify that you've installed Go by opening a command prompt and typing the following command:

$ go version

- Confirm that the command prints the installed version of Go.

- Open the MSI file you downloaded and follow the prompts to install Go.

By default, the installer will install Go to Program Files or Program Files (x86). You can change the location as needed. After installing, you will need to close and reopen any open command prompts so that changes to the environment made by the installer are reflected at the command prompt.

- Verify that you've installed Go.

- In Windows, click the Start menu.

- In the menu's search box, type cmd, then press the Enter key.

- In the Command Prompt window that appears, type the following command:

$ go version

- Confirm that the command prints the installed version of Go.

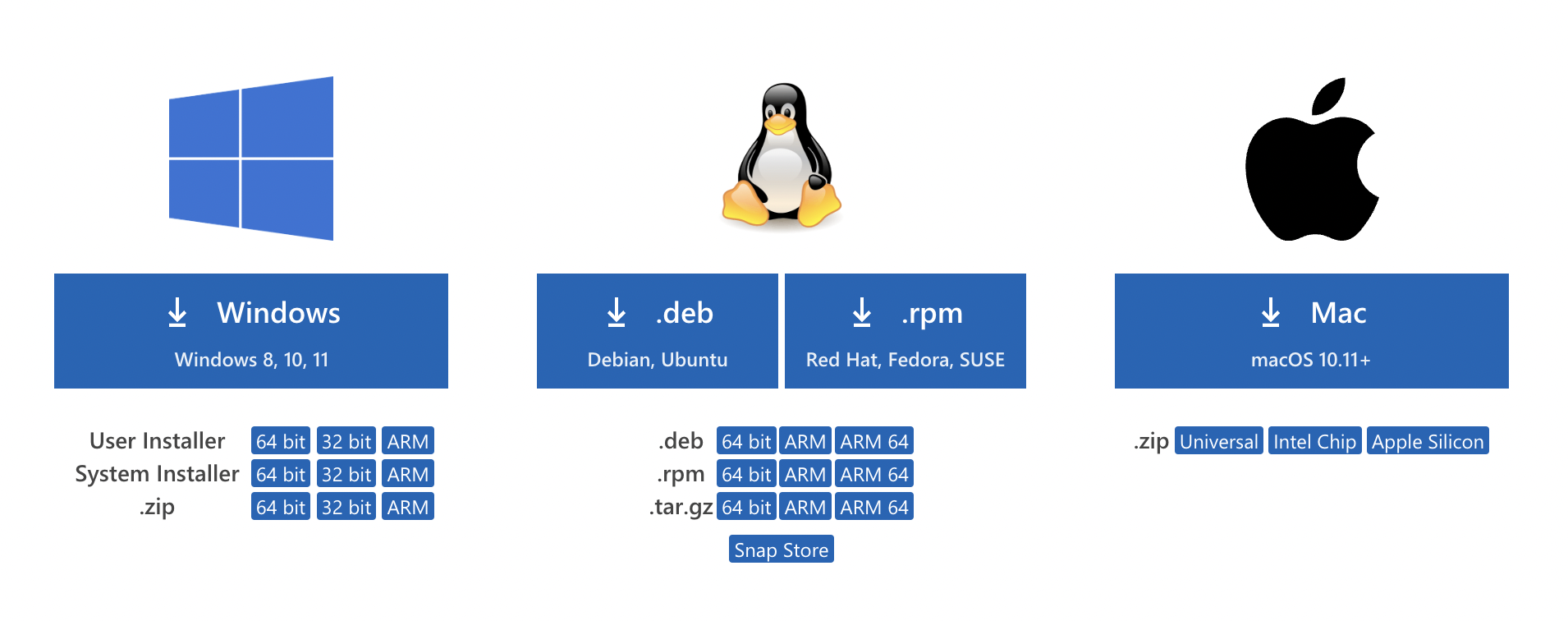

In this course, I will be using VS Code and you can download it from here.

Feel free to use any other code editor you prefer.

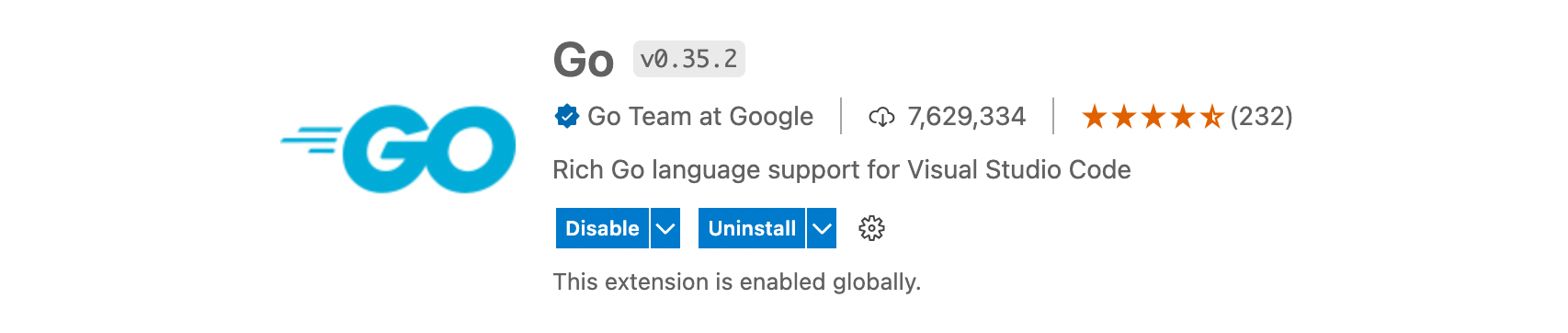

Make sure to also install the Go extension which makes is easier to work with Go in VS Code.

This is it for the installation and setup of Go, let's start the course and write our first hello world!

Let's write our first hello world program, we can start by initializing a module. For that, we can use the go mod command.

$ go mod init exampleBut wait...what's a module? Don't worry we will discuss that soon! But for now, assume that the module is basically a collection of Go packages.

Moving ahead, let's now create a main.go file and write a program that simply prints hello world.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}If you're wondering, fmt is part of the Go standard library which is a set of core packages provided by the language.

Now, let's quickly breakdown what we did here, or rather the structure of a Go program.

First, we defined a package such as main.

package mainThen, we have some imports.

import "fmt"Last but not least, is our main function which acts as an entry point for our application, just like in other languages like C, Java, or C#.

func main() {

...

}Remember, the goal here is to keep a mental note, and later in the course, we'll learn about functions, imports, and other things in detail!

Finally, to run our code, we can simply use go run command.

$ go run main.go

Hello World!Congratulations, you just wrote your first Go program!

In this tutorial, we will learn about variables. We will also learn about the different data types that Go provides us.

Let's start with declaring a variable.

This is also known as declaration without initialization:

var foo stringDeclaration with initialization:

var foo string = "Go is awesome"Multiple declarations:

var foo, bar string = "Hello", "World"

// OR

var (

foo string = "Hello"

bar string = "World"

)Type is omitted but will be inferred:

var foo = "What's my type?"Shorthand declaration, here we omit var keyword and type is always implicit. This is how we will see variables being declared most of the time. We also use the := for declaration plus assignment.

foo := "Shorthand!"Note: Shorthand only works inside function bodies

We can also declare constants with the const keyword. Which as the name suggests, are fixed values that cannot be reassigned.

const constant = "This is a constant"It is also important to note that, only constants can be assigned to other constants.

const a = 10

const b = a // ✅ Works

var a = 10

const b = a // ❌ a (variable of type int) is not constant (InvalidConstInit)Perfect! Now let's look at some basic data types available in Go. Starting with string.

In Go, a string is a sequence of bytes.

They are declared either using double quotes or backticks which can span multiple lines

var name string = "My name is Go"

var bio string = `I am statically typed.

I was designed at Google.`Next is bool which is used to store boolean values. It can have two possible values - true or false.

var value bool = false

var isItTrue bool = trueOperators

We can use the following operators on boolean types

| Logical | && | ! |

| Equality | == | != |

Now, let's talk about numeric types, starting with

Signed and Unsigned integers

Go has several built-in integer types of varying sizes for storing signed and unsigned integers

The size of generic int and uint type is platform dependent. This means it is 32-bits wide on a 32-bit system and 64-bits wide on a 64-bit system.

var i int = 404 // Platform dependent

var i8 int8 = 127 // -128 to 127

var i16 int16 = 32767 // -2^15 to 2^15 - 1

var i32 int32 = -2147483647 // -2^31 to 2^31 - 1

var i64 int64 = 9223372036854775807 // -2^63 to 2^63 - 1Similar to signed integers, we have unsigned integers.

var ui uint = 404 // Platform dependent

var ui8 uint8 = 255 // 0 to 255

var ui16 uint16 = 65535 // 0 to 2^16

var ui32 uint32 = 2147483647 // 0 to 2^32

var ui64 uint64 = 9223372036854775807 // 0 to 2^64

var uiptr uintptr // Integer representation of a memory addressIf you noticed, there's also an unsigned integer pointer uintptr type, which is an integer representation of a memory address. It is not recommended to use this, so we don't have to worry about it.

So which one should we use?

It is recommended that whenever we need an integer value, we should just use int unless we have a specific reason to use a sized or unsigned integer type.

Integer alias types

Next, let's discuss integer alias types.

Byte and Rune

Golang has two additional integer types called byte and rune that are aliases for uint8 and int32 data types respectively.

type byte = uint8

type rune = int32A rune represents a unicode code point.

var b byte = 'a'

var r rune = '🍕'Floating point

Next, we have floating point types which are used to store numbers with a decimal component.

Go has two floating point types float32 and float64. Both types follow IEEE-754 standard.

The default type for floating point values is float64

var f32 float32 = 1.7812 // IEEE-754 32-bit

var f64 float64 = 3.1415 // IEEE-754 64-bitOperators

Go provides several operators for performing operations on numeric types.

Complex

There are 2 complex types in Go, complex128 where both real and imaginary parts are float64 and complex64 where real and imaginary are float32.

We can define complex numbers either using the built-in complex function or as literals.

var c1 complex128 = complex(10, 1)

var c2 complex64 = 12 + 4iNow let's discuss zero values. So in Go any variable declared without an explicit initial value are given their zero value. For example, let's declare some variables and see:

var i int

var f float64

var b bool

var s string

fmt.Printf("%v %v %v %q\n", i, f, b, s)$ go run main.go

0 0 false ""So, as we can see int and float are assigned as 0, bool as false, and string as an empty string. This is quite different from how other languages do it. For example, most languages initialize unassigned variables as null or undefined.

This is great, but what are those percent symbols in our Printf function? As you've already guessed, they are used for formatting and we will learn about them later.

Moving on, now that we have seen how data types work, let's see how to do type conversion.

i := 42

f := float64(i)

u := uint(f)

fmt.Printf("%T %T", f, u)$ go run main.go

float64 uintAnd as we can see, it prints the type as float64 and uint.

Note that this is different from parsing

Alias types were introduced in Go 1.9. They allow developers to provide an alternate name for an existing type and use it interchangeably with the underlying type.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyAlias = string

func main() {

var str MyAlias = "I am an alias"

fmt.Printf("%T - %s", str, str) // Output: string - I am an alias

}Lastly, we have defined types that unlike alias types do not use an equals sign.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyDefined string

func main() {

var str MyDefined = "I am defined"

fmt.Printf("%T - %s", str, str) // Output: main.MyDefined - I am defined

}But wait...what's the difference?

So, defined types do more than just give a name to a type.

It first defines a new named type with an underlying type. However, this defined type is different from any other type, including its underline type.

Hence, it cannot be used interchangeably with the underlying type like alias types.

It's a bit confusing at first, hopefully, this example will make things clear.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyAlias = string

type MyDefined string

func main() {

var alias MyAlias

var def MyDefined

// ✅ Works

var copy1 string = alias

// ❌ Cannot use str (variable of type MyDefined) as string value in variable

var copy2 string = def

fmt.Println(copy1, copy2)

}As we can see, we cannot use the defined type interchangeably with the underlying type, unlike alias types.

In this tutorial, we will learn about string formatting or sometimes also known as templating.

fmt package contains lots of functions. So to save time, we will discuss the most frequently used functions. Let's start with fmt.Print inside our main function.

...

fmt.Print("What", "is", "your", "name?")

fmt.Print("My", "name", "is", "golang")

...$ go run main.go

Whatisyourname?MynameisgolangAs we can see, Print does not format anything, it simply takes a string and prints it.

Next, we have Println which is the same as Print but it adds a new line at the end and also inserts space between the arguments.

...

fmt.Println("What", "is", "your", "name?")

fmt.Println("My", "name", "is", "golang")

...$ go run main.go

What is your name?

My name is golangThat's much better!

Next, we have Printf also known as "Print Formatter", which allows us to format numbers, strings, booleans, and much more.

Let's look at an example.

...

name := "golang"

fmt.Println("What is your name?")

fmt.Printf("My name is %s", name)

...$ go run main.go

What is your name?

My name is golangAs we can see that %s was substituted with our name variable.

But the question is what is %s and what does it mean?

So, these are called annotation verbs and they tell the function how to format the arguments. We can control things like width, types, and precision with these and there are lots of them. Here's a cheatsheet.

Now, let's quickly look at some more examples. Here we will try to calculate a percentage and print it to the console.

...

percent := (3/5) * 100

fmt.Printf("%f", percent)

...$ go run main.go

58.181818Let's say we want just 58.18 which is 2 points precision, we can do that as well by using .2f

Also, to add an actual percent sign, we will need to escape it.

...

percent := (3/5) * 100

fmt.Printf("%.2f %%", percent)

...$ go run main.go

58.18 %This brings us to Sprint, Sprintln, and Sprintf. These are basically the same as the print functions, the only difference being they return the string instead of printing it.

Let's take a look at an example.

...

s := fmt.Sprintf("hex:%x bin:%b", 10 ,10)

fmt.Println(s)

...$ go run main.go

hex:a bin:1010So, as we can see Sprintf formats our integer as hex or binary and returns it as a string.

Lastly, we have multiline string literals, which can be used like this.

...

msg := `

Hello from

multiline

`

fmt.Println(msg)

...Great! But this is just the tip of the iceberg...so make sure to checkout the go doc for fmt package.

For those who are coming from C/C++ background, this should feel natural, but if you're coming from, let's say Python or JavaScript, this might be a little strange at first. But it is very powerful and you'll see this functionality used quite extensively.

et's talk about flow control, starting with if/else.

This works pretty much the same as you expect but the expression doesn't need to be surrounded by parentheses ().

func main() {

x := 10

if x > 5 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 5")

} else if x > 10 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 10")

} else {

fmt.Println("else case")

}

}$ go run main.go

x is gt 5We can also compact our if statements.

func main() {

if x := 10; x > 5 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 5")

}

}Note: This pattern is quite common

Next, we have switch statement, which is often a shorter way to write conditional logic.

In Go, the switch case only runs the first case whose value is equal to the condition expression and not all the cases that follow. Hence, unlike other languages, break statement is automatically added at the end of each case.

This means that it evaluates cases from top to bottom, stopping when a case succeeds. Let's take a look at an example:

func main() {

day := "monday"

switch day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}

}$ go run main.go

time to work!Switch also supports shorthand declaration like this.

switch day := "monday"; day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}We can also use the fallthrough keyword to transfer control to the next case even though the current case might have matched.

switch day := "monday"; day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

fallthrough

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}And if we run this, we'll see that after the first case matches the switch statement continues to the next case because of the fallthrough keyword.

$ go run main.go

time to work!

let's partyWe can also use it without any condition, which is the same as switch true.

x := 10

switch {

case x > 5:

fmt.Println("x is greater")

default:

fmt.Println("x is not greater")

}Now, let's turn our attention toward loops.

So in Go, we only have one type of loop which is the for loop.

But it's incredibly versatile. Same as if statement, for loop, doesn't need any parenthesis () unlike other languages.

Let's start with the basic for loop.

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}The basic for loop has three components separated by semicolons:

- init statement: which is executed before the first iteration.

- condition expression: which is evaluated before every iteration.

- post statement: which is executed at the end of every iteration.

Break and continue

As expected, Go also supports both break and continue statements for loop control. Let's try a quick example:

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i < 2 {

continue

}

fmt.Println(i)

if i > 5 {

break

}

}

fmt.Println("We broke out!")

}So, the continue statement is used when we want to skip the remaining portion of the loop, and break statement is used when we want to break out of the loop.

Also, Init and post statements are optional, hence we can make our for loop behave like a while loop as well.

func main() {

i := 0

for ;i < 10; {

i += 1

}

}Note: we can also remove the additional semi-colons to make it a little cleaner

Lastly, If we omit the loop condition, it loops forever, so an infinite loop can be compactly expressed. This is also known as the forever loop.

func main() {

for {

// do stuff here

}

}In this tutorial, we will discuss how we work with functions in Go. So, let's start with a simple function declaration.

func myFunction() {}And we can call or execute it as follows.

...

myFunction()

...Let's pass some parameters to it.

func main() {

myFunction("Hello")

}

func myFunction(p1 string) {

fmt.Printtln(p1)

}$ go run main.goAs we can see it prints our message. We can also do a short hand declaration if the consecutive parameters have the same type. For example:

func myNextFunction(p1, p2 string) {}Now let's also return a value.

func main() {

s := myFunction("Hello")

fmt.Println(s)

}

func myFunction(p1 string) string {

msg := fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

return msg

}Why return one value at a time, when we can do more? Go also supports multiple returns!

func main() {

s, i := myFunction("Hello")

fmt.Println(s, i)

}

func myFunction(p1 string) (string, int) {

msg := fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

return msg, 10

}Another cool feature is named returns, where return values can be named and treated as their own variables.

func myFunction(p1 string) (s string, i int) {

s = fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

i = 10

return

}Notice how we added a return statement without any arguments, this is also known as naked return.

I will say that, although this feature is interesting, please use it with care as this might reduce readability for larger functions.

Next, let's talk about functions as values, in Go functions are first class and we can use them as values. So, let's clean up our function and try it out!

func myFunction() {

fn := func() {

fmt.Println("inside fn")

}

fn()

}We can also simplify this by making fn an anonymous function.

func myFunction() {

func() {

fmt.Println("inside fn")

}()

}Notice how we execute it using the parenthesis at the end

Why stop there? let's also return a function and hence create something called a closure. A simple definition can be that a closure is a function value that references variables from outside its body.

Closures are lexically scoped, which means functions can access the values in scope when defining the function.

func myFunction() func(int) int {

sum := 0

return func(v int) int {

sum += v

return sum

}

}...

add := myFunction()

add(5)

fmt.Println(add(10))

...As we can see, we get a result of 15 as sum variable is bound to the function. This is a very powerful concept and definitely a must know.

Now let's look at variadic functions, which are functions that can take zero or multiple arguments using the ... ellipses operator.

An example here would be a function that can add a bunch of values.

func main() {

sum := add(1, 2, 3, 5)

fmt.Println(sum)

}

func add(values ...int) int {

sum := 0

for _, v := range values {

sum += v

}

return sum

}Pretty cool huh? Also, don't worry about the range keyword, we will discuss it later in the course.

Fun fact: fmt.Println is a variadic function, that's how we were able to pass multiple values to it.

In Go, init is a special lifecycle function which is executed prior to the main function.

Similar to main, the init function does not take any arguments nor returns any value. Let's see how it works with an example.

package main

import "fmt"

func init() {

fmt.Println("Before main!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("Running main")

}As expected, the init function was executed before the main function.

$ go run main.go

Before main!

Running mainUnlike main, there can be more than one init function in a single or multiple files.

For multiple init in a single file, their processing is done in the order of their declaration, while init declared in multiple files are processed according to the lexicographic filename order.

package main

import "fmt"

func init() {

fmt.Println("Before main!")

}

func init() {

fmt.Println("Hello again?")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("Running main")

}And if we run this, we'll see the init functions were executed in order they were declared.

$ go run main.go

Before main!

Hello again?

Running mainThe init function is optional and is particularly used for any global setup which might be essential for our program, such as establishing a database connection, fetching configuration files, setting up environment variables, etc.

Lastly, let's discuss the defer keyword, which lets us postpones the execution of a function until the surrounding function returns.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("I am finished")

fmt.Println("Doing some work...")

}Can we use multiple defer functions? Absolutely, this brings us to what is known as defer stack. Let's take a look at an example

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("I am finished")

defer fmt.Prinlnt("Are you?")

fmt.Println("Doing some work...")

}$ go run main.go

Doing some work...

Are you?

I am finishedAs we can see, defer statements are stacked and executed in a last in first out manner.

So, Defer is incredibly useful and is commonly used for doing cleanup or error handling.

Functions can also be used with generics but we will discuss them later in the course.

In this tutorial, we will learn about modules.

Simply defined, A module is a collection of Go packages stored in a file tree with a go.mod file at its root, provided the directory is outside $GOPATH/src.

Go modules were introduced in Go 1.11, which brings native support for versions and modules. Earlier, we needed the GO111MODULE=on flag to turn on the modules functionality when it was experimental. But now after Go 1.13 modules mode is the default for all development.

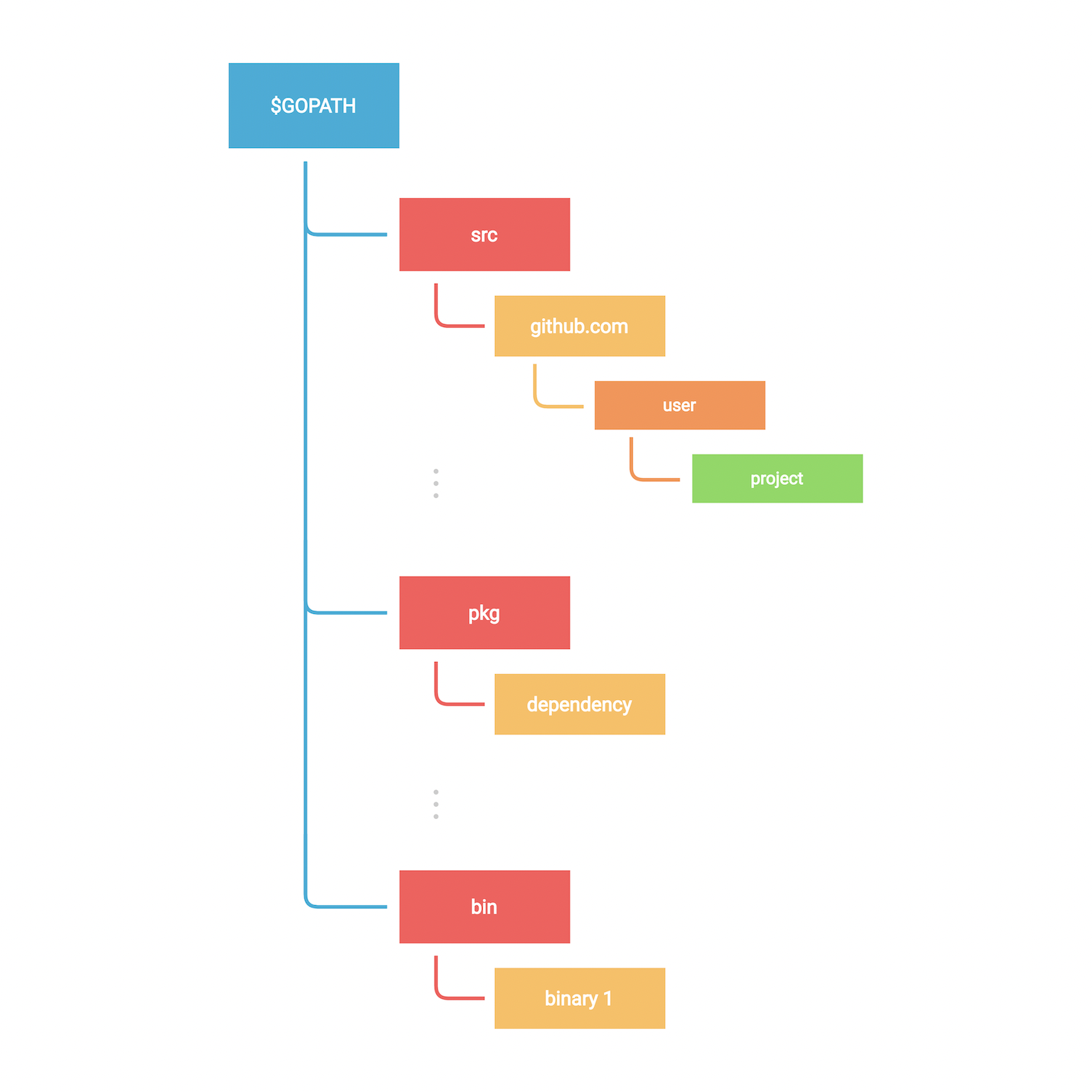

But wait what is GOPATH?

Well, GOPATH is a variable that defines the root of your workspace and it contains the following folders:

- src: contains Go source code organized in a hierarchy.

- pkg: contains compiled package code.

- bin: contains compiled binaries and executables.

Like earlier, let's create a new module using go mod init command which creates a new module and initializes the go.mod file that describes it.

$ go mod init exampleThe important thing to note here is that a Go module can correspond to a Github repository as well if you plan to publish this module. For example:

$ go mod init exampleNow, let's explore go.mod which is the file that defines the module's module path and also the import path used for the root directory, and its dependency requirements.

module <name>

go <version>

require (

...

)And if we want to add a new dependency, we will use go install command:

$ go install github.com/rs/zerologAs we can see a go.sum file was also created. This file contains the expected hashes of the content of the new modules.

We can list all the dependencies using go list command as follows:

$ go list -m allIf the dependency is not used, we can simply remove it using go mod tidy command:

$ go mod tidyFinishing up our discussion on modules, let's also discuss vendoring.

Vendoring is the act of making your own copy of the 3rd party packages your project is using. Those copies are traditionally placed inside each project and then saved in the project repository.

This can be done through go mod vendor command.

So let's reinstall the removed module using go mod tidy.

package main

import "github.com/rs/zerolog/log"

func main() {

log.Info().Msg("Hello")

}$ go mod tidy

go: finding module for package github.com/rs/zerolog/log

go: found github.com/rs/zerolog/log in github.com/rs/zerolog v1.26.1$ go mod vendor├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── go.work

├── main.go

└── vendor

├── github.com

│ └── rs

│ └── zerolog

│ └── ...

└── modules.txt

In this tutorial, we will learn about multi-module workspaces that were introduced in Go 1.18.

Workspaces allow us to work with multiple modules simultaneously without having to edit go.mod files for each module. Each module within a workspace is treated as a root module when resolving dependencies.

To understand this better, let's start by creating a hello module.

$ mkdir workspaces && cd workspaces

$ mkdir hello && cd hello

$ go mod init helloFor demonstration purposes, I will add a simple main.go and install an example package.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"golang.org/x/example/stringutil"

)

func main() {

result := stringutil.Reverse("Hello Workspace")

fmt.Println(result)

}$ go get golang.org/x/example

go: downloading golang.org/x/example v0.0.0-20220412213650-2e68773dfca0

go: added golang.org/x/example v0.0.0-20220412213650-2e68773dfca0And if we run this, we should see our output in reverse.

$ go run main.go

ecapskroW olleHThis is great, but what if we want to modify the stringutil module that our code depends on?

Until now, we had to do it using the replace directive in the go.mod file, but now let's see how we can use workspaces here.

So let's create our workspace in the workspace directory.

$ go work initThis will create a go.work file.

$ cat go.work

go 1.18We will also add our hello module to the workspace.

$ go work use ./helloThis should update the [go.work](http://go.work) file with a reference to our hello module.

go 1.18

use ./helloNow, let's download and modify the stringutil package and update the Reverse function implementation.

$ git clone https://go.googlesource.com/example

Cloning into 'example'...

remote: Total 204 (delta 39), reused 204 (delta 39)

Receiving objects: 100% (204/204), 467.53 KiB | 363.00 KiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (39/39), done.example/stringutil/reverse.go

func Reverse(s string) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("I can do whatever!! %s", s)

}Finally, let's add example package to our workspace.

$ go work use ./example

$ cat go.work

go 1.18

use (

./example

./hello

)Perfect, now if we run our hello module we will notice that the Reverse function has been modified.

$ go run hello

I can do whatever!! Hello WorkspaceThis is a very underrated feature from Go 1.18 but it is quite useful in certain circumstances.

In this tutorial, we will talk about packages.

A package is nothing but a directory containing one or more Go source files, or other Go packages.

This means every Go source file must belong to a package and package declaration is done at top of every source file as follows.

package <package_name>So far, we've done everything inside of package main. By convention, executable programs (by that I mean the ones with the main package) are called Commands, others are simply called Packages.

The main package should also contain a main() function which is a special function that acts as the entry point of an executable program.

Let's take a look at an example by creating our own package custom and adding some source files to it such as code.go.

package customBefore we proceed any further, we should talk about imports and exports. Just like other languages, go also has a concept of imports and exports but it's very elegant.

Basically, any value (like a variable or function) can be exported and visible from other packages if they have been defined with an upper case identifier.

Let's try an example in our custom package.

package custom

var value int = 10 // Will not be exported

var Value int = 20 // Will be exportedAs we can see lower case identifiers will not be exported and will be private to the package it's defined in. In our case the custom package.

That's great but how do we import or access it? Well, same as we've been doing so far unknowingly. Let's go to our main.go file and import our custom package.

Here we can refer to it using the module we had initialized in our go.mod file earlier.

---go.mod---

module example

go 1.18

---main.go--

package main

import "example/custom"

func main() {

custom.Value

}Notice how the package name is the last name of the import path

We can import multiple packages as well like this.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"example/custom"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(custom.Value)

}We can also alias our imports to avoid collisions like this.

package main

import (

"fmt"

abcd "example/custom"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(abcd.Value)

}External Dependencies

In Go, we are not only limited to working with local packages, we can also install external packages using go install command as we saw earlier.

So let's download a simple logging package github.com/rs/zerolog/log.

$ go install github.com/rs/zerologpackage main

import (

"github.com/rs/zerolog/log"

abcd "example/custom"

)

func main() {

log.Print(abcd.Value)

}Also, make sure to checkout the go doc of packages you install, which is usually located in the project's readme file. go doc parses the source code and generates documentation in HTML format. Reference to It is usually located in readme files.

Lastly, I will add that, Go doesn't have a particular "folder structure" convention, always try to organize your packages in a simple and intuitive way.

During our module discussion, we discussed some go commands related to go modules, let's now discuss some other important commands.

Starting with go fmt, which formats the source code and it's enforced by that language so that we can focus on how our code should work rather than how our code should look.

$ go fmtThis might seem a little weird at first especially if you're coming from a javascript or python background like me but frankly, it's quite nice not to worry about linting rules.

Next, we have go vet which reports likely mistakes in our packages.

So, if I go ahead and make a mistake in the syntax, and then run go vet.

It should notify me of the errors.

$ go vetNext, we have go env which simply prints all the go environment information, we'll learn about some of these build-time variable later.

Lastly, we have, go doc which shows documentation for package or symbol, here's an example of the format package.

$ go doc -src fmt PrintfLet's use go help command to see what other commands are available.

$ go helpAs we can see, we have:

go fix finds Go programs that use old APIs and rewrites them to use newer ones.

go generate is usually used for code generation.

go install compiles and install packages and dependencies.

go clean is used for cleaning files that are generated by compilers.

Some other very important commands are go build and go test but we will learn about them in detail later in the course.

Building static binaries is one of the best features of Go which enables us to ship our code efficiently.

We can do this very easily using the go build command.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("I am a binary!")

}$ go buildThis should produce a binary with the name of our module. For example, here we have example.

We can also specify the output.

$ go build -o appNow to run this, we simply need to execute it.

$ ./app

I am a binary!Yes, it's as simple as that!

Now, let's talk about some important build time variables, starting with:

GOOSandGOARCH

these environment variables help use build go programs for different operating systems and underlying processor architectures.

We can list all the supported architecture using go tool command.

$ go tool dist list

android/amd64

ios/amd64

js/wasm

linux/amd64

windows/arm64

.

.

.Here's an example for building a window's executable from macOS!

$ GOOS=windows GOARCH=amd64 go build -o app.exeCGO_ENABLED

This variable allows us to configure CGO, which is a way in Go to call C code.

This helps us to produce a statically linked binary that works without any external dependencies.

This is quite helpful for, let's say when we want to run our go binaries in a docker container with minimum external dependencies.

Here's an example of how to use it:

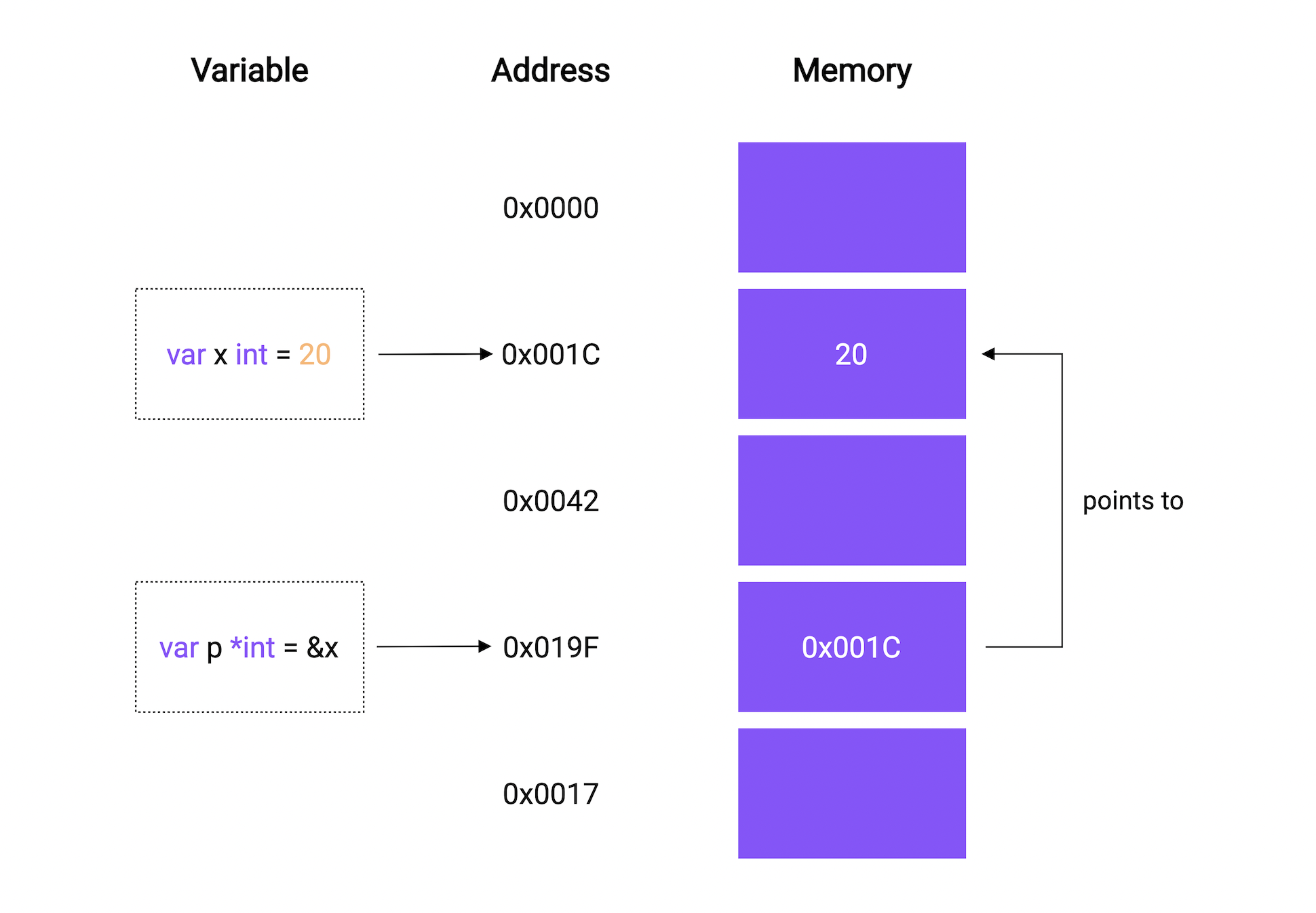

$ CGO_ENABLED=0 go build -o appIn this tutorial, we will discuss pointers. So what are Pointers?

Simply defined, a Pointer is a variable that is used to store the memory address of another variable.

It can be used like this:

var x *TWhere T is the type such as int, string, float, and so on.

Let's try a simple example and see it in action.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var p *int

fmt.Println(p)

}$ go run main.go

nilHmm, this prints nil, but what is nil?

So nil is a predeclared identifier in Go that represents zero value for pointers, interfaces, channels, maps, and slices.

This is just like what we learned in the variables and datatypes section, where we saw that uninitialized int has a zero value of 0, a bool has false, and so on.

Okay, now let's assign a value to the pointer.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := 10

var p *int = &a

fmt.Println("address:", p)

}We use the & ampersand operator to refer to a variable's memory address.

$ go run main.go

0xc0000b8000This must be the value of the memory address of the variable a.

We can also use the * asterisk operator to value stored in the variable that the pointer points to. This is called dereferencing.

For example, we can access the value of the variable a through the pointer p using that * asterisk operator.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := 10

var p *int = &a

fmt.Println("address:", p)

fmt.Println("value:", *p)

}$ go run main.go

address: 0xc000018030

value: 10We can not only access it but change it as well through the pointer.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := 10

var p *int = &a

fmt.Println("before", a)

fmt.Println("address:", p)

*p = 20

fmt.Println("after:", a)

}$ go run main.go

before 10

address: 0xc000192000

after: 20I think this is pretty neat!

Pointers can also be used as arguments for a function when we need to pass some data by reference.

Here's an example:

myFunction(&a)

...

func myFunction(ptr *int) {}There's also another way to initialize a pointer. We can use the new function which takes a type as an argument, allocates enough memory to accommodate a value of that type, and returns a pointer to it.

Here's an example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

p := new(int)

*p = 100

fmt.Println("value", *p)

fmt.Println("address", p)

}$ go run main.go

value 100

address 0xc000018030Here's an interesting idea...can we create a pointer to a pointer. And the answer is yes! Yes, we can.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

p := new(int)

*p = 100

p1 := &p

fmt.Println("P value", *p, " address", p)

fmt.Println("P1 value", *p1, " address", p)

fmt.Println("Dereferenced value", **p1)

}$ go run main.go

P value 100 address 0xc0000be000

P1 value 0xc0000be000 address 0xc0000be000

Dereferenced value 100Notice how the value of p1 matches the address of p.

Also, it is important to know that pointers in Go do not support pointer arithmetic like in C or C++.

p1 := p * 2 // Compiler Error: invalid operationHowever, we can compare two pointers of the same type for equality using a == operator.

p := &a

p1 := &a

fmt.Println(p == p1)This brings us to the million-dollar question, why do we need pointers?

Well, there's no definite answer for that, and pointers are just another useful feature that helps us mutate our data efficiently without copying a large amount of data.

And can be applied to tons of use cases.

Lastly, I will add that if you are coming from a language with no notion of pointers, don't panic and try to form a mental model of how pointers work.

In this tutorial, we will learn about structs.

So, a struct is a user-defined type that contains a collection of named fields. Basically, it is used to group related data together to form a single unit.

If you're coming from an objected-oriented background, think of structs as lightweight classes which that support composition but not inheritance.

We can define a struct like this:

type Person struct {}We use the type keyword to introduce a new type, followed by the name and then the struct keyword to indicate that we're defining a struct.

Now, let's give it some fields:

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

}And, if the fields have the same type, we can collapse them as well.

type Person struct {

FirstName, LastName string

Age int

}Now that we have our struct, we can declare it the same as other datatypes.

func main() {

var p1 Person

fmt.Println("Person 1:", p1)

}$ go run main.go

Person 1: { 0}As we can see, all the struct fields are initialized with their zero values. So the FirstName and LastName are set to "" empty string and Age is set to 0.

We can also initialize it as "struct literal".

func main() {

var p1 Person

fmt.Println("Person 1:", p1)

var p2 = Person{FirstName: "Karan", LastName: "Pratap Singh", Age: 22}

fmt.Println("Person 2:", p2)

}For readability, we can separate by new line but this will also require a trialing comma.

var p2 = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}$ go run main.go

Person 1: { 0}

Person 2: {Karan Pratap Singh 22}We can also initialize only a subset of fields.

func main() {

var p1 Person

fmt.Println("Person 1:", p1)

var p2 = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}

fmt.Println("Person 2:", p2)

var p3 = Person{

FirstName: "Tony",

LastName: "Stark",

}

fmt.Println("Person 3:", p3)

}$ go run main.go

Person 1: { 0}

Person 2: {Karan Pratap Singh 22}

Person 3: {Tony Stark 0}As we can see, the age field of person 3 has defaulted to the zero value.

Go structs also supports initialization without field names.

func main() {

var p1 Person

fmt.Println("Person 1:", p1)

var p2 = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}

fmt.Println("Person 2:", p2)

var p3 = Person{

FirstName: "Tony",

LastName: "Stark",

}

fmt.Println("Person 3:", p3)

var p4 = Person{"Bruce", "Wayne"}

fmt.Println("Person 4:", p4)

}But here's the catch, we will need to provide all the values during the initialization or it will fail.

$ go run main.go

# command-line-arguments

./main.go:30:27: too few values in Person{...} var p4 = Person{"Bruce", "Wayne", 40}

fmt.Println("Person 4:", p4)We can also declare an anonymous struct.

func main() {

var p1 Person

fmt.Println("Person 1:", p1)

var p2 = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}

fmt.Println("Person 2:", p2)

var p3 = Person{

FirstName: "Tony",

LastName: "Stark",

}

fmt.Println("Person 3:", p3)

var p4 = Person{"Bruce", "Wayne", 40}

fmt.Println("Person 4:", p4)

var a = struct {

Name string

}{"Golang"}

fmt.Println("Anonymous:", a)

}Let's clean up our example a bit and see how we can access individual fields.

func main() {

var p = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}

fmt.Println("FirstName", p.FirstName)

}We can also create a pointer to structs as well.

func main() {

var p = Person{

FirstName: "Karan",

LastName: "Pratap Singh",

Age: 22,

}

ptr := &p

fmt.Println((*ptr).FirstName)

fmt.Println(ptr.FirstName)

}Both statements are equal as in Go we don't need to explicitly dereference the pointer. We can also use the built-in new function.

func main() {

p := new(Person)

p.FirstName = "Karan"

p.LastName = "Pratap Singh"

p.Age = 22

fmt.Println("Person", p)

}$ go run main.go

Person &{Karan Pratap Singh 22}As a side note, two structs are equal if all their corresponding fields are equal as well.

func main() {

var p1 = Person{"a", "b", 20}

var p2 = Person{"a", "b", 20}

fmt.Println(p1 == p2)

}$ go run main.go

trueNow let's learn what is exported and unexported fields in a struct. Same as the rules for variables and functions, if a struct field is declared with a lower case identifier, it will not be exported and only be visible to the package it is defined in.

type Person struct {

FirstName, LastName string

Age int

zipCode string

}So, the zipCode field won't be exported. Also, the same goes for the Person struct, if we rename it as person, it won't be exported as well.

type person struct {

FirstName, LastName string

Age int

zipCode string

}As we discussed earlier, Go doesn't necessarily support inheritance, but we can do something similar with embedding

type Person struct {

FirstName, LastName string

Age int

}

type SuperHero struct {

Person

Alias string

}So, our new struct will have all the properties of the original struct. And it should behave the same as our normal struct.

func main() {

s := SuperHero{}

s.FirstName = "Bruce"

s.LastName = "Wayne"

s.Age = 40

s.Alias = "batman"

fmt.Println(s)

}$ go run main.go

{{Bruce Wayne 40} batman}However, this is usually not recommended and in most cases, composition is preferred. So rather than embedding, we will just define it as a normal field.

type Person struct {

FirstName, LastName string

Age int

}

type SuperHero struct {

Person Person

Alias string

}Hence, we can re-write our example with composition as well.

func main() {

p := Person{"Bruce", "Wayne", 40}

s := SuperHero{p, "batman"}

fmt.Println(s)

}$ go run main.go

{{Bruce Wayne 40} batman}Again, there is no right or wrong here, but nonetheless, embedding comes in handy sometimes.

A struct tag is just a tag that allows us to attach metadata information to the field which can be used for custom behavior using the reflect package.

Let's learn how we can define struct tags.

type Animal struct {

Name string `key:"value1"`

Age int `key:"value2"`

}You will often find tags in encoding packages, such as XML, JSON, YAML, ORMs, and Configuration management.

Here's a tags example for the JSON encoder.

type Animal struct {

Name string `json:"name"`

Age int `json:"age"`

}Finally, let's discuss the properties of structs.

Structs are value types. When we assign one struct variable to another, a new copy of the struct is created and assigned.

Similarly, when we pass a struct to another function, the function gets its own copy of the struct.

package main

import "fmt"

type Point struct {

X, Y float64

}

func main() {

p1 := Point{1, 2}

p2 := p1 // Copy of p1 is assigned to p2

p2.X = 2

fmt.Println(p1) // Output: {1 2}

fmt.Println(p2) // Output: {2 2}

}Empty struct occupies zero bytes of storage.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"unsafe"

)

func main() {

var s struct{}

fmt.Println(unsafe.Sizeof(s)) // Output: 0

}Let's talk about methods, or sometimes also known as function receivers.

Technically, Go is not an object-oriented programming language. It doesn't have classes, objects, and inheritance.

However, Go has types. And, you can define methods on types.

A method is nothing but a function with a special receiver argument. Let's see how we can declare methods.

func (variable T) Name(params) (returnTypes) {}The receiver argument has a name and a type. It appears between the func keyword and the method name.

For example, let's define a Car struct.

type Car struct {

Name string

Year int

}Now, let us define a method like IsLatest which will tell us if a car was manufactured within the last 5 years.

func (c Car) IsLatest() bool {

return c.Year >= 2017

}As you can see, we can access the instance of Car using the receiver variable c. I like to think of it as this keyword from the object-oriented world.

Now we should be able to call this method after we initialize our struct, just like we do with classes in other languages.

func main() {

c := Car{"Tesla", 2021}

fmt.Println("IsLatest", c.IsLatest())

}All the examples that we saw previously had a value receiver.

With a value receiver, the method operates on a copy of the value passed to it. Therefore, any modifications done to the receiver inside the methods are not visible to the caller.

For example, let's make another method called UpdateName which will update the name of the Car.

func (c Car) UpdateName(name string) {

c.Name = name

}Now, let's run this.

func main() {

c := Car{"Tesla", 2021}

c.UpdateName("Toyota")

fmt.Println("Car:", c)

}$ go run main.go

Car: {Tesla 2021}Seems like the name wasn't updated, so now let's switch our receiver to pointer type and try again.

func (c *Car) UpdateName(name string) {

c.Name = name

}$ go run main.go

Car: {Toyota 2021}As expected, methods with pointer receivers can modify the value to which the receiver points. Such modifications are visible to the caller of the method as well.

Let's also see some properties of the methods!

- Go is smart enough to interpret our function call correctly, and hence, pointer receiver method calls are just syntactic sugar provided by Go for convenience.

(&c).UpdateName(...)- We can omit the variable part of the receiver as well if we're not using it.

func (Car) UpdateName(...) {}- Methods are not limited to structs but can also be used with non-struct types as well.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyInt int

func (i MyInt) isGreater(value int) bool {

return i > MyInt(value)

}

func main() {

i := MyInt(10)

fmt.Println(i.isGreater(5))

}So the question is, why methods instead of functions?

As always, there's no particular answer for this, and in no way one is better than the other. Instead, they should be used appropriately when the situation arrives.

One thing I can think of right now is that methods can help us avoid naming conflicts.

Since a method is tied to a particular type, we can have the same method names for multiple receivers.

But generally, it might just come down to preference? Such as "method calls are much easier to read and understand than function calls" or the other way around.

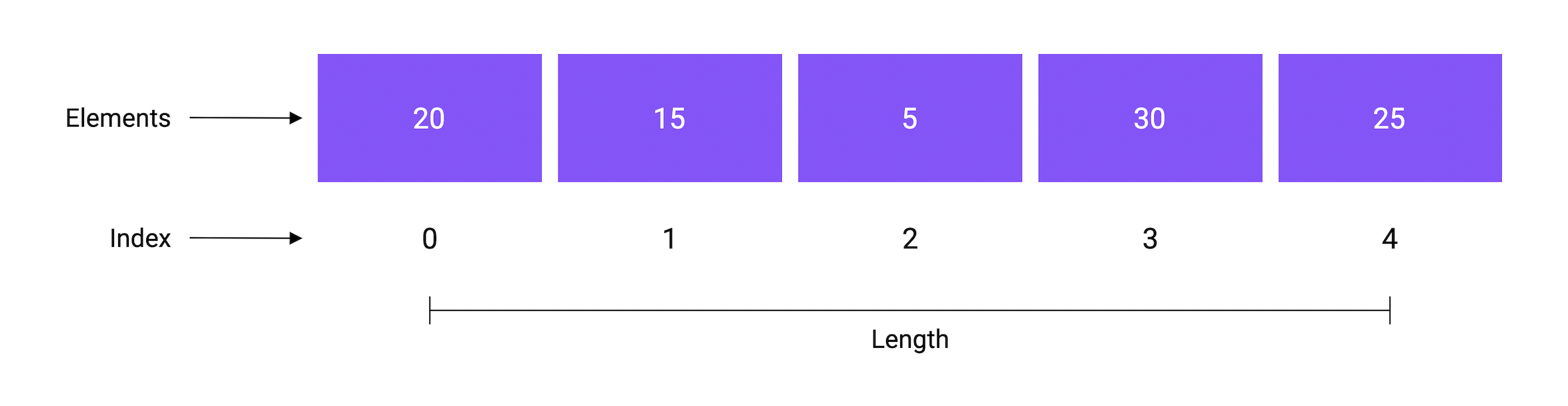

In this tutorial, we will learn about arrays and slices in Go.

An array is a fixed-size collection of elements of the same type. The elements of the array are stored sequentially and can be accessed using their index.

We can declare an array as follows:

var a [n]THere, n is the length and T can be any type like integer, string, or user-defined structs.

Now, let's declare an array of integers with length 4 and print it.

func main() {

var arr [4]int

fmt.Println(arr)

}$ go run main.go

[0 0 0 0]By default, all the array elements are initialized with the zero value of the corresponding array type.

We can also initialize an array using an array literal.

var a [n]T = [n]T{V1, V2, ... Vn}func main() {

var arr = [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

fmt.Println(arr)

}$ go run main.go

[1 2 3 4]We can even do a shorthand declaration.

...

arr := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}And similar to other languages, we can access the elements using the index as they're stored sequentially.

func main() {

arr := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

fmt.Println(arr[0])

}$ go run main.go

1Now, let's talk about iteration.

So, there are multiple ways to iterate over arrays.

The first one is using the for loop with the len function which gives us the length of the array.

func main() {

arr := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

for i := 0; i < len(arr); i++ {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Element: %d\n", i, arr[i])

}

}$ go run main.go

Index: 0, Element: 1

Index: 1, Element: 2

Index: 2, Element: 3

Index: 3, Element: 4Another way is to use the range keyword with the for loop.

func main() {

arr := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

for i, e := range arr {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Element: %d\n", i, e)

}

}$ go run main.go

Index: 0, Element: 1

Index: 1, Element: 2

Index: 2, Element: 3

Index: 3, Element: 4As we can see, our example works the same as before.

But the range keyword is quite versatile and can be used in multiple ways.

for i, e := range arr {} // Normal usage of range

for _, e := range arr {} // Omit index with _ and use element

for i := range arr {} // Use index only

for range arr {} // Simply loop over the arrayAll the arrays that we created so far are one dimensional. We can also create multi-dimensional arrays in Go.

Let's take a look at an example:

func main() {

arr := [2][4]int{

{1, 2, 3, 4},

{5, 6, 7, 8},

}

for i, e := range arr {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Element: %d\n", i, e)

}

}$ go run main.go

Index: 0, Element: [1 2 3 4]

Index: 1, Element: [5 6 7 8]We can also let the compiler infer the length of the array by using ... ellipses instead of the length.

func main() {

arr := [...][4]int{

{1, 2, 3, 4},

{5, 6, 7, 8},

}

for i, e := range arr {

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Element: %d\n", i, e)

}

}$ go run main.go

Index: 0, Element: [1 2 3 4]

Index: 1, Element: [5 6 7 8]Now let's talk about some properties of arrays.

The array's length is part of its type. So, the array a and b are completely distinct types, and we cannot assign one to the other.

This also means that we cannot resize an array, because resizing an array would mean changing its type.

package main

func main() {

var a = [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

var b [2]int = a // Error, cannot use a (type [4]int) as type [2]int in assignment

}Arrays in Go are value types unlike other languages like C, C++, and Java where arrays are reference types.

This means that when we assign an array to a new variable or pass an array to a function, the entire array is copied.

So, if we make any changes to this copied array, the original array won't be affected and will remain unchanged.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a = [7]string{"Mon", "Tue", "Wed", "Thu", "Fri", "Sat", "Sun"}

var b = a // Copy of a is assigned to b

b[0] = "Monday"

fmt.Println(a) // Output: [Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun]

fmt.Println(b) // Output: [Monday Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun]

}I know what you're thinking, arrays are useful but a bit inflexible due to the limitation caused by their fixed size.

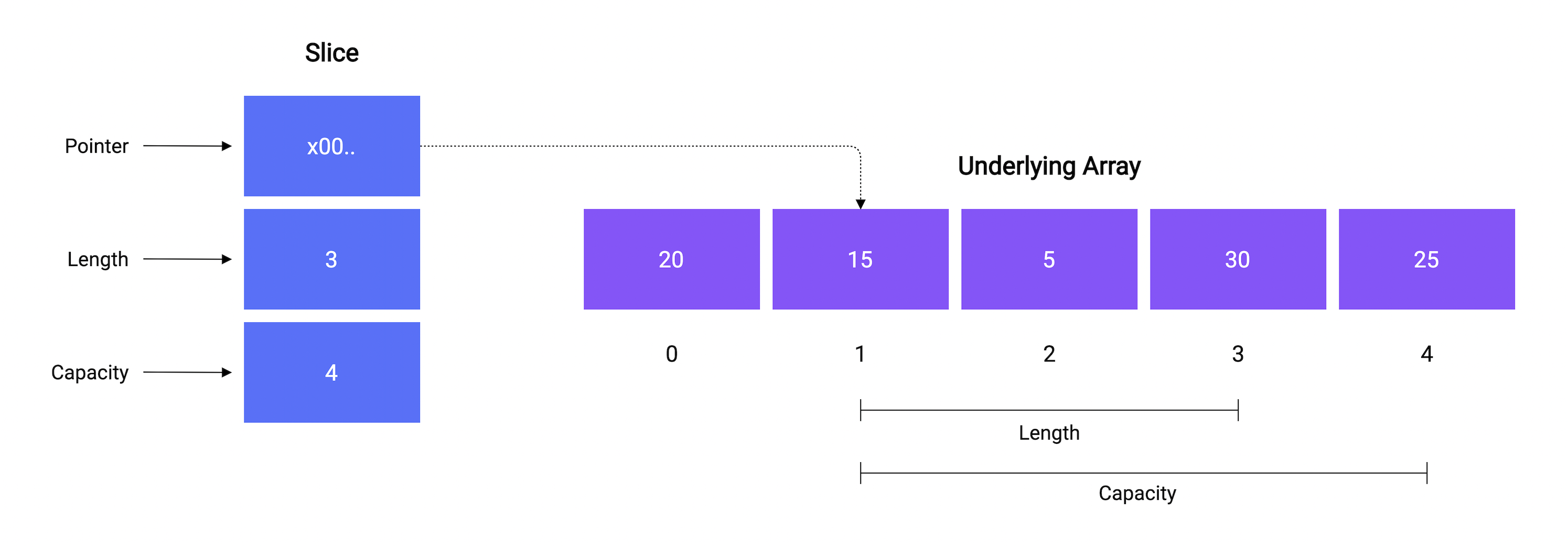

This brings us to Slice, so what is a slice?

A Slice is a segment of an array. Slices build on arrays and provide more power, flexibility, and convenience.

A slice consists of three things:

- A pointer reference to an underlying array.

- The length of the segment of the array that the slice contains.

- And, the capacity, which is the maximum size up to which the segment can grow.

Just like len function, we can determine the capacity of a slice using the built-in cap function. Here's an example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := [5]int{20, 15, 5, 30, 25}

s := a[1:4]

// Output: Array: [20 15 5 30 25], Length: 5, Capacity: 5

fmt.Printf("Array: %v, Length: %d, Capacity: %d\n", a, len(a), cap(a))

// Output: Slice [15 5], Length: 3, Capacity: 4

fmt.Printf("Slice: %v, Length: %d, Capacity: %d", s, len(s), cap(s))

}Don't worry, we are going to discuss everything shown here in detail.

Let's see how we can declare a slice.

var s []TAs we can see, we don't need to specify any length. Let's declare a slice of integers and see how it works.

func main() {

var s []string

fmt.Println(s)

fmt.Println(s == nil)

}$ go run main.go

[]

trueSo, unlike arrays, the zero value of a slice is nil.

There are multiple ways to initialize our slice. One way is to use the built-in make function.

make([]T, len, cap) []Tfunc main() {

var s = make([]string, 0, 0)

fmt.Println(s)

}$ go run main.go

[]Similar to arrays, we can use the slice literal to initialize our slice.

func main() {

var s = []string{"Go", "TypeScript"}

fmt.Println(s)

}$ go run main.go

[Go TypeScript]Another way is to create a slice from an array. Since a slice is a segment of an array, we can create a slice from index low to high as follows.

a[low:high]func main() {

var a = [4]string{

"C++",

"Go",

"Java",

"TypeScript",

}

s1 := a[0:2] // Select from 0 to 2

s2 := a[:3] // Select first 3

s3 := a[2:] // Select last 2

fmt.Println("Array:", a)

fmt.Println("Slice 1:", s1)

fmt.Println("Slice 2:", s2)

fmt.Println("Slice 3:", s3)

}$ go run main.go

Array: [C++ Go Java TypeScript]

Slice 1: [C++ Go]

Slice 2: [C++ Go Java]

Slice 3: [Java TypeScript]Missing low index implies 0 and missing high index implies len(a).

The thing to note here is we can create a slice from other slices too and not just arrays.

var a = []string{

"C++",

"Go",

"Java",

"TypeScript",

}We can iterate over a slice in the same way you iterate over an array, by using the for loop with either len function or range keyword.

So now, let's talk about built-in slice functions provided in Go.

- copy

The copy() function copies elements from one slice to another. It takes 2 slices, a destination, and a source. It also returns the number of elements copied.

func copy(dst, src []T) intLet's see how we can use it.

func main() {

s1 := []string{"a", "b", "c", "d"}

s2 := make([]string, len(s1))

e := copy(s2, s1)

fmt.Println("Src:", s1)

fmt.Println("Dst:", s2)

fmt.Println("Elements:", e)

}$ go run main.go

Src: [a b c d]

Dst: [a b c d]

Elements: 4As expected, our 4 elements from the source slice were copied to the destination slice.

- append

Now, let's look at how we can append data to our slice using the built-in append function which appends new elements at the end of a given slice.

It takes a slice and a variable number of arguments. It then returns a new slice containing all the elements.

append(slice []T, elems ...T) []TLet's try it in an example by appending elements to our slice.

func main() {

s1 := []string{"a", "b", "c", "d"}

s2 := append(s1, "e", "f")

fmt.Println("s1:", s1)

fmt.Println("s2:", s2)

}$ go run main.go

s1: [a b c d]

s2: [a b c d e f]As we can see, the new elements were appended and a new slice was returned.

But if the given slice doesn't have sufficient capacity for the new elements then a new underlying array is allocated with a bigger capacity.

All the elements from the underlying array of the existing slice are copied to this new array, and then the new elements are appended.

Finally, let's discuss some properties of slices.

Slices are reference types, unlike arrays.

This means modifying the elements of a slice will modify the corresponding elements in the referenced array.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := [7]string{"Mon", "Tue", "Wed", "Thu", "Fri", "Sat", "Sun"}

s := a[0:2]

s[0] = "Sun"

fmt.Println(a) // Output: [Sun Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun]

fmt.Println(s) // Output: [Sun Tue]

}Slices can be used with variadic types as well.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

values := []int{1, 2, 3}

sum := add(values...)

fmt.Println(sum)

}

func add(values ...int) int {

sum := 0

for _, v := range values {

sum += v

}

return sum

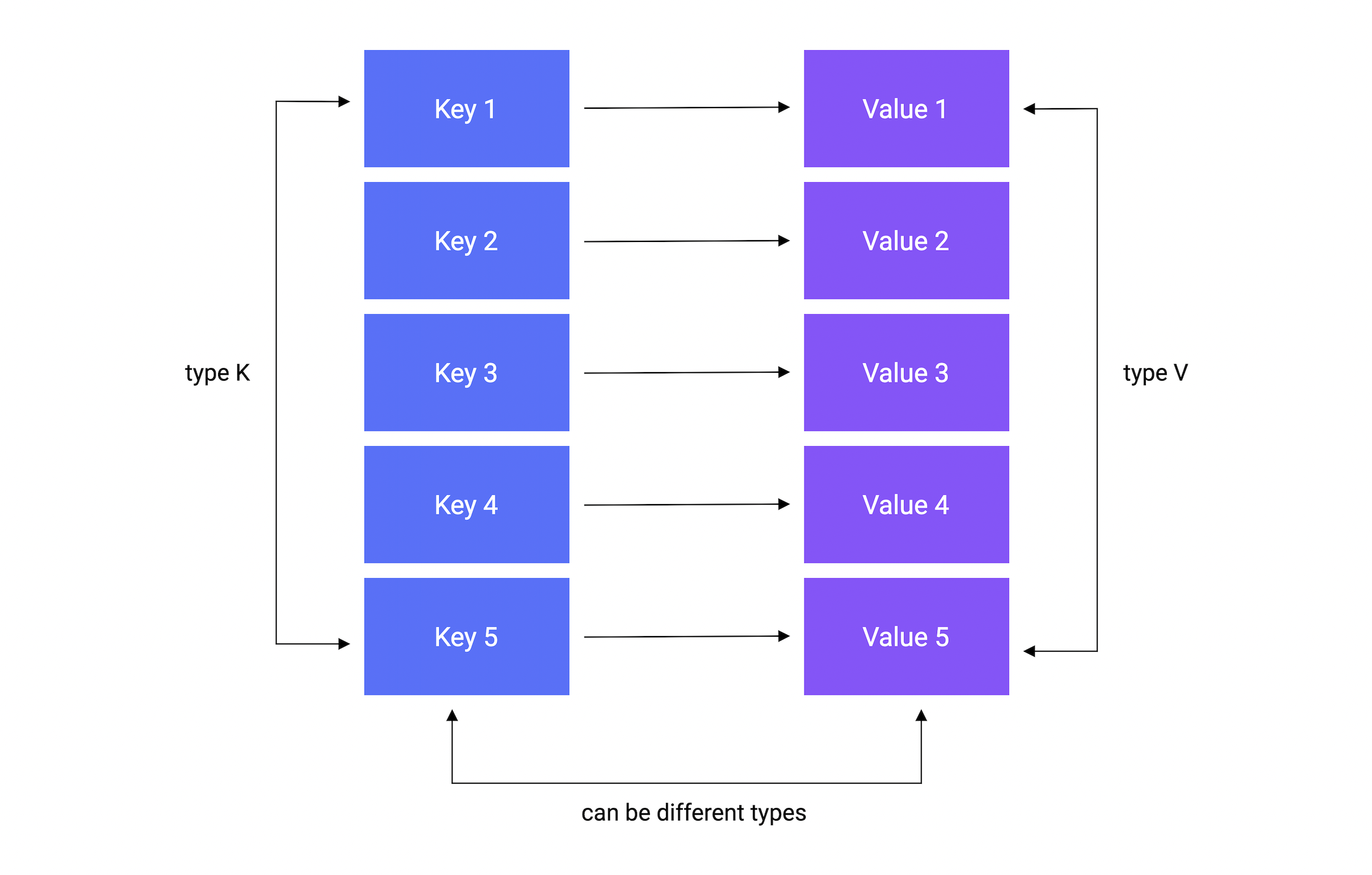

}So, Go provides a built-in map type, and we'll learn how to use it.

But, the question is what are maps? And why do we need them?

Well, A map is an unordered collection of key-value pairs. It maps keys to values. The keys are unique within a map while the values may not be.

It is used for fast lookups, retrieval, and deletion of data based on keys. It is one of the most used data structures.

Let's start with the declaration.

A map is declared using the following syntax:

var m map[K]VWhere K is the key type and V is the value type.

For example, here's how we can declare a map of string keys to int values.

func main() {

var m map[string]int

fmt.Println(m)

}$ go run main.go

nilAs we can see, the zero value of a map is nil.

A nilmap has no keys. Moreover, any attempt to add keys to a nilmap will result in a runtime error.

There are multiple ways to initialize a map.

make function

We can use the built-in make function, which allocates memory for referenced data types and initializes their underlying data structures.

func main() {

var m = make(map[string]int)

fmt.Println(m)

}$ go run main.go

map[]map literal

Another way is using map literal.

func main() {

var m = map[string]int{

"a": 0,

"b": 1,

}

fmt.Println(m)

}Note that the last trailing comma is necessary

$ go run main.go

map[a:0 b:1]As always, we can use our custom types as well.

type User struct {

Name string

}

func main() {

var m = map[string]User{

"a": User{"Peter"},

"b": User{"Seth"},

}

fmt.Println(m)

}We can even remove the value type and Go will figure it out!

var m = map[string]User{

"a": {"Peter"},

"b": {"Seth"},

}$ go run main.go

map[a:{Peter} b:{Seth}]Now, let's see how we can add a value to our map.

func main() {

var m = map[string]User{

"a": {"Peter"},

"b": {"Seth"},

}

m["c"] = User{"Steve"}

fmt.Println(m)

}$ go run main.go

map[a:{Peter} b:{Seth} c:{Steve}]We can also retrieve our values from the map using the key.

...

c := m["c"]

fmt.Println("Key c:", c)$ go run main.go

key c: {Steve}What if we use a key that is not present in the map?

...

d := m["d"]

fmt.Println("Key d:", d)Yes, you guessed it! we will get the zero value of the map's value type.

$ go run main.go

Key c: {Steve}

Key d: {}When you retrieve the value assigned to a given key, it returns an additional boolean value as well. The boolean variable will be true if the key exists, and false otherwise.

Let's try this in an example:

...

c, ok := m["c"]

fmt.Println("Key c:", c, ok)

d, ok := m["d"]

fmt.Println("Key d:", d, ok)$ go run main.go

Key c: {Steve} Present: true

Key d: {} Present: falseWe can also update the value for a key by simply re-assigning a key.

...

m["a"] = "Roger"$ go run main.go

map[a:{Roger} b:{Seth} c:{Steve}]Or, we can delete the key using the built-in delete function.

Here's how the syntax looks:

...

delete(m,The first argument is the map, and the second is the key we want to delete.

The delete() function doesn't return any value. Also, it doesn't do anything if the key doesn't exist in the map.

$ go run main.go

map[a:{Roger} c:{Steve}]Similar to arrays or slices, we can iterate over maps with the range keyword.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var m = map[string]User{

"a": {"Peter"},

"b": {"Seth"},

}

m["c"] = User{"Steve"}

for key, value := range m {

fmt.Println("Key: %s, Value: %v", key, value)

}

}$ go run main.go

Key: c, Value: {Steve}

Key: a, Value: {Peter}

Key: b, Value: {Seth}Note that a map is an unordered collection, and therefore the iteration order of a map is not guaranteed to be the same every time we iterate over it.

Lastly, let's talk about map properties.

Maps are reference types, which means when we assign a map to a new variable, they both refer to the same underlying data structure.

Therefore, changes done by one variable will be visible to the other.

package main

import "fmt"

type User struct {

Name string

}

func main() {

var m1 = map[string]User{

"a": {"Peter"},

"b": {"Seth"},

}

m2 := m1

m2["c"] = User{"Steve"}

fmt.Println(m1) // Output: map[a:{Peter} b:{Seth} c:{Steve}]

fmt.Println(m2) // Output: map[a:{Peter} b:{Seth} c:{Steve}]

}In this section, let's talk about the interfaces.

So, an interface in Go is an abstract type that is defined using a set of method signatures. The interface defines the behavior for similar types of objects.

Here, behavior is a key term that we will discuss shortly.

Let's take a look at an example to understand this better.

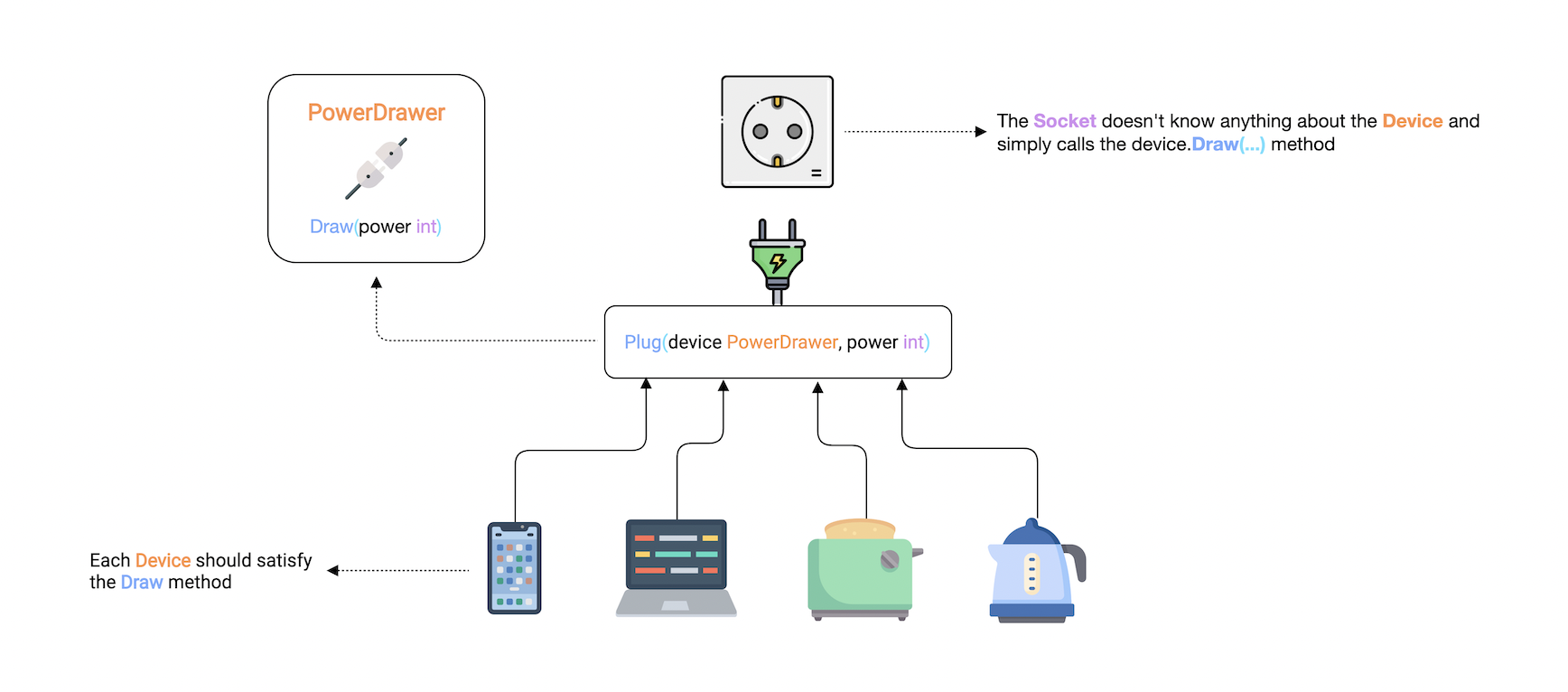

One of the best real-world examples of interfaces is the power socket. Imagine that we need to connect different devices to the power socket.

Let's try to implement this. Here are the device types we will be using.

type mobile struct {

brand string

}

type laptop struct {

cpu string

}

type toaster struct {

amount int

}

type kettle struct {

quantity string

}

type socket struct{}Now, let's define a Draw method on a type, let's say mobile. Here we will simply print the properties of the type.

func (m mobile) Draw(power int) {

fmt.Printf("%T -> brand: %s, power: %d", m, m.brand, power)

}Great, now we will define the Plug method on the socket type which accepts our mobile type as an argument.

func (socket) Plug(device mobile, power int) {

device.Draw(power)

}Let's try to "connect" or "plug in" the mobile type to our socket type in the main function.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

m := mobile{"Apple"}

s := socket{}

s.Plug(m, 10)

}And if we run this we'll see the following.

$ go run main.go

main.mobile -> brand: Apple, power: 10This is interesting, but let's say now we want to connect our laptop type.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

m := mobile{"Apple"}

l := laptop{"Intel i9"}

s := socket{}

s.Plug(m, 10)

s.Plug(l, 50) // Error: cannot use l as mobile value in argument

}As we can see, this will throw an error.

What should we do now? Define another method? Such as PlugLaptop?

Sure, but then every time we add a new device type we will need to add a new method to the socket type as well and that's not ideal.

This is where the interface comes in. Essentially, we want to define a contract that, in the future, must be implemented.

We can simply define an interface such as PowerDrawer and use it in our Plug function to allow any device that satisfies the criteria, which is that the type must have a Draw method matching the signature that the interface requires.

And anyways, the socket doesn't need to know anything about our device and can simply call the Draw method.

Now let's try to implement our PowerDrawer interface. Here's how it will look.

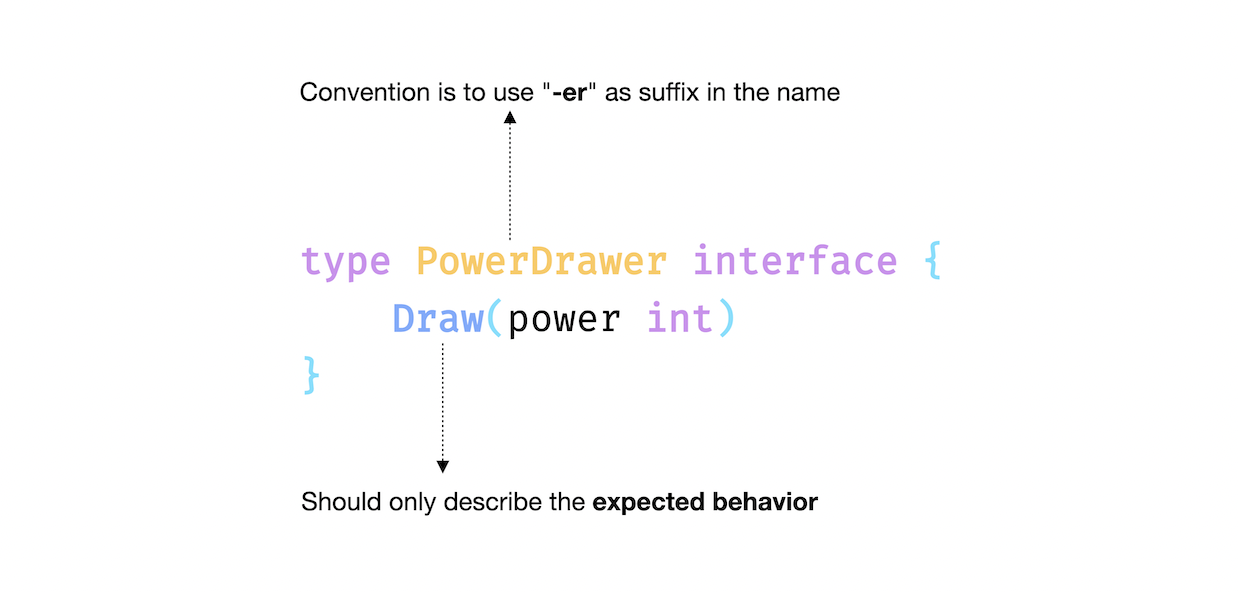

The convention is to use "-er" as a suffix in the name. And as we discussed earlier, an interface should only describe the expected behavior. Which in our case is the Draw method.

type PowerDrawer interface {

Draw(power int)

}Now, we need to update our Plug method to accept a device that implements the PowerDrawer interface as an argument.

func (socket) Plug(device PowerDrawer, power int) {

device.Draw(power)

}And to satisfy the interface, we can simply add Draw methods to all the device types.

type mobile struct {

brand string

}

func (m mobile) Draw(power int) {

fmt.Printf("%T -> brand: %s, power: %d\n", m, m.brand, power)

}

type laptop struct {

cpu string

}

func (l laptop) Draw(power int) {

fmt.Printf("%T -> cpu: %s, power: %d\n", l, l.cpu, power)

}

type toaster struct {

amount int

}

func (t toaster) Draw(power int) {

fmt.Printf("%T -> amount: %d, power: %d\n", t, t.amount, power)

}

type kettle struct {

quantity string

}

func (k kettle) Draw(power int) {

fmt.Printf("%T -> quantity: %s, power: %d\n", k, k.quantity, power)

}Now, we can connect all our devices to the socket with the help of our interface!

func main() {

m := mobile{"Apple"}

l := laptop{"Intel i9"}

t := toaster{4}

k := kettle{"50%"}

s := socket{}

s.Plug(m, 10)

s.Plug(l, 50)

s.Plug(t, 30)

s.Plug(k, 25)

}And just as we expected, it works.

$ go run main.go

main.mobile -> brand: Apple, power: 10

main.laptop -> cpu: Intel i9, power: 50

main.toaster -> amount: 4, power: 30

main.kettle -> quantity: Half Empty, power: 25But why is this considered such a powerful concept?

Well, an interface can help us decouple our types. For example, because we have the interface, we don't need to update our socket implementation. We can just define a new device type with a Draw method.

Unlike other languages, Go Interfaces are implemented implicitly, so we don't need something like an implements keyword. This means that a type satisfies an interface automatically when it has "all the methods" of the interface.

Next, let's talk about the empty interface. An empty interface can take on a value of any type.

Here's how we declare it.

var x interface{}But why do we need it?

Empty interfaces can be used to handle values of unknown types.

Some examples are:

- Reading heterogeneous data from an API.

- Variables of an unknown type, like in the

fmt.Prinlnfunction.

To use a value of type empty interface{}, we can use type assertion or a type switch to determine the type of the value.

A type assertion provides access to an interface value's underlying concrete value.

For example:

func main() {

var i interface{} = "hello"

s := i.(string)

fmt.Println(s)

}This statement asserts that the interface value holds a concrete type and assigns the underlying type value to the variable.

We can also test whether an interface value holds a specific type.

A type assertion can return two values:

- The first one is the underlying value.

- The second is a boolean value that reports whether the assertion succeeded.

s, ok := i.(string)

fmt.Println(s, ok)This can help us test whether an interface value holds a specific type or not.

In a way, this is similar to how we read values from a map.

And If this is not the case then, ok will be false and the value will be the zero value of the type, and no panic will occur.

f, ok := i.(float64)

fmt.Println(f, ok)But if the interface does not hold the type, the statement will trigger a panic.

f = i.(float64)

fmt.Println(f) // Panic!$ go run main.go

hello

hello true

0 false

panic: interface conversion: interface {} is string, not float64Here, a switch statement can be used to determine the type of a variable of type empty interface{}.

var t interface{}

t = "hello"

switch t := t.(type) {

case string:

fmt.Printf("string: %s\n", t)

case bool:

fmt.Printf("boolean: %v\n", t)

case int:

fmt.Printf("integer: %d\n", t)

default:

fmt.Printf("unexpected: %T\n", t)

}And if we run this, we can verify that we have a string type.

$ go run main.go

string: helloLet's discuss some properties of interfaces.

Zero value

The zero value of an interface is nil.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyInterface interface {

Method()

}

func main() {

var i MyInterface

fmt.Println(i) // Output: <nil>

}Embedding

We can embed interfaces like structs.

For example

type interface1 interface {

Method1()

}

type interface2 interface {

Method2()

}

type interface3 interface {

interface1

interface2

}Values

Interface values are comparable.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyInterface interface {

Method()

}

type MyType struct{}

func (MyType) Method() {}

func main() {

t := MyType{}

var i MyInterface = MyType{}

fmt.Println(t == i)

}Interface Values

Under the hood, an interface value can be thought of as a tuple consisting of a value and a concrete type.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyInterface interface {

Method()

}

type MyType struct {

property int

}

func (MyType) Method() {}

func main() {

var i MyInterface

i = MyType{10}

fmt.Printf("(%v, %T)\n", i, i) // Output: ({10}, main.MyType)

}With that, we covered interfaces in Go.

It's a really powerful feature, but remember, "Bigger the interface, the weaker the abstraction" - Rob Pike.

In this tutorial, let's talk about error handling.

Notice I said errors and not exceptions as there is no exception handling in Go.

Instead, we can just return a built-in error type which is an interface type.

type error interface {

Error() string

}We will circle back to this shortly. First, let's try to understand the basics.

So, let's declare a simple Divide function which, as the name suggests,, will divide integer a by b.

func Divide(a, b int) int {

return a/b

}Great. Now, we want to return an error, let's say, to prevent the division by zero. This brings us to error construction.

There are multiple ways to do this, but we will look at the two most common one.

The first is by using the New function provided by the errors package.

package main

import "errors"

func main() {}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, errors.New("cannot divide by zero")

}

return a/b, nil

}Notice, how we return error with the result. And if there is no error we simply return nil as it is the zero value of an error because after all, it's an interface.

But how do we handle it? So, for that, let's call the Divide function in our main function.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

result, err := Divide(4, 0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

// Do something with the error

return

}

fmt.Println(result)

// Use the result

}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {...}$ go run main.go

cannot divide by zeroAs you can see, we simply check if the error is nil and build our logic accordingly. This is considered quite idiomatic in Go and you will see this being used a lot.

Another way to construct our errors is by using the fmt.Errorf function.

This function is similar to fmt.Sprintf and it lets us format our error. But instead of returning a string, it returns an error.

It is often used to add some context or detail to our errors.

...

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("cannot divide %d by zero", a)

}

return a/b, nil

}And it should work similarly.

$ go run main.go

cannot divide 4 by zeroAnother important technique in Go is defining expected Errors so they can be checked explicitly in other parts of the code. These are sometimes referred to as sentinel errors.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

var ErrDivideByZero = errors.New("cannot divide by zero")

func main() {...}

func Divide(a, b int) (int, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, ErrDivideByZero

}

return a/b, nil

}In Go, it is considered conventional to prefix the variable with Err. For example, ErrNotFound.

But what's the point?

So, this becomes useful when we need to execute a different branch of code if a certain kind of error is encountered.

For example, now we can check explicitly which error occurred using the errors.Is function.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

result, err := Divide(4, 0)

if err != nil {

switch {

case errors.Is(err, ErrDivideByZero):

fmt.Println(err)

// Do something with the error

default:

fmt.Println("no idea!")

}

return

}

fmt.Println(result)