-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 10

/

lec05.Rmd

438 lines (321 loc) · 23.8 KB

/

lec05.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

---

title: "Multivariate Plots"

output:

html_document:

fig_caption: no

number_sections: yes

toc: yes

toc_float: false

collapsed: no

---

```{r set-options, echo=FALSE}

options(width = 105)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(dev='png', dpi=300, cache=FALSE)

pdf.options(useDingbats = TRUE)

klippy::klippy(position = c('top', 'right'))

```

<p><span style="color: #00cc00;">NOTE: This page has been revised for Winter 2021, but may undergo further edits.</span></p>

# Introduction #

Multivariate descriptive displays or plots are designed to reveal the relationship among several variables simulataneously.. As was the case when examining relationships among pairs of variables, there are several basic characteristics of the relationship among sets of variables that are of interest. These include:

- the *forms* of the relationships

- the *strength* of the relationships, and

- the *dependence* of the relationships on external (usually to the pairs of variables being examined) circumstances.

The easiest way to get the data for the multivariate plotting examples is to load a copy of the workspace `geog495.RData`

```{r load, echo=FALSE, include=FALSE}

load(".Rdata")

```

# Enhanced basic plots #

## Enhanced 2-D Scatter plots ##

The scatter diagram or scatter plot is the workhorse bivariate plot, and can be enhanced to illustrate relationships among three (or four) variables.

### The color-coded scatter plot (color plot) ###

A basic "color plot"" displays the values of three variables at a time using colored symbols, where the value of one variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the X-axis and the value of a second variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the Y-axis, and the value of the third variable is used to determine the color of the symbol.

The Specmap data set illustrated the variations over time of oxygen-isotope data (that records global ice volume, negative values mean little ice or globally warm conditions, positive values, large ice sheets, and globally cold conditions) which should theoretically depend on insolation (incoming solar radiation) at 65 N, which has been called the "pacemaker of the ice ages". However, a simple plot of Insolation and O18 (and correlation) suggests otherwise:

```{r plot1, fig.width=4, fig.asp=1, message=FALSE, results="hide"}

attach(specmap)

plot(O18 ~ Insol, pch=16, cex=0.6)

```

The cloud of points (at first glace) is quite amorphous, and the correlation coefficient is also quite low:

```{r cor1}

cor(O18, Insol)

```

Plotting `O18` as a function of `Age`, and color coding the symbols by `Insol` levels, reveals the nature of the control of ice volume by insolation:

```{r plot2}

library(RColorBrewer)

library(classInt) # class-interval recoding library

plotvar <- Insol

nclr <- 8

plotclr <- brewer.pal(nclr,"PuOr")

plotclr <- plotclr[nclr:1] # reorder colors

class <- classIntervals(plotvar, nclr, style="quantile")

colcode <- findColours(class, plotclr)

plot(O18 ~ Age, ylim=c(2.5,-2.5), type="l")

points(O18 ~ Age, pch=16, col=colcode, cex=1.5)

detach(specmap)

```

Now it's possible to see that warm (and warming) intervals (points near the top of the plot) tend to have high (orange) solar radiation values, while cooling and cold intervals follow periods of declining solar radiation (blue).

## Color and symbols ##

Information from four variables at a time can also be displayed. In this example for the Summit Cr. data (a scatter plot of `WidthWS` as a function of `CumLen`), the plotting character is determined by Reach and its color by HU. Although these are factors, numerical variables could also be plotted.

```{r plot3}

attach(sumcr)

plot(WidthWS ~ CumLen, pch=as.integer(Reach), col=as.integer(HU))

legend(25, 2, c("Reach A", "Reach B", "Reach C"), pch=c(1,2,3), col=1)

legend(650, 2, c("Glide", "Pool", "Riffle"), pch=1, col=c(1,2,3))

detach(sumcr)

```

Note the use of two applications of the `legend()` function: the circles indicate the upstream grazed reach (reach A), the triangles indicate the cattle-exclosure reach (B), and the pluses indicate the downstream grazed reach (C), while black indicates glides, red indicates pools, and green indicates riffles.

## The bubble plot ##

The bubble plot displays the values of three variables at a time using graduated symbols (usually circles), where the value of one variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the X-axis and the value of a second variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the Y-axis, and the value of the third variable is used to determine the size of the symbol. Here’s a crude map of the elevations of the Oregon climate stations, which reflects the overall topography of the state. Note the use of the full names of the variables.

```{r plot4, message=FALSE}

plot(orstationc$lon, orstationc$lat, type="n")

symbols(orstationc$lon, orstationc$lat, circles=orstationc$elev, inches=0.1, add=T)

```

[[Back to top]](lec05.html)

# 3-D Scatter plots #

3-D scatter plots (as distinct from scatter plot matrices involving three variables), illustrate the relationship among three variables by plotting them in a three-dimensional "workbox". There are a number of basic enhancements of the basic 3-D scatter plot, such as the addition of drop lines, lines connecting points, symbol modification and so on.

## 3-D point-cloud plot ##

This plot displays the values of three variables at a time by plotting them in a 3-D "workbox" where the value of one variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the X-axis and the value of a second variable determines the relative position of the symbol along the Y-axis, and the value of the third variable is used to determine the relative position along the Z-axis. This plot makes use of the `lattice` package.

```{r plot5}

library(lattice)

cloud(orstationc$elev ~ orstationc$lon*orstationc$lat)

```

Notice that you can still see the outline of the state, because elevation is a fairly well behaved variable.

## 3-D Scatter plots (using the `scatterplot3d` package) ##

The `scatterplot3d` package (by Ligges and Mächler) provides a way of constructing a 3-point cloud display with some nice embellishments. The first part of the code, like in making maps, does some setup like determining the number of colors to plot and getting their definitions. The second block produces the plot.

```{r plot6}

library(scatterplot3d)

library(RColorBrewer)

# get colors for labeling the points

plotvar <- orstationc$pann # pick a variable to plot

nclr <- 8 # number of colors

plotclr <- brewer.pal(nclr,"PuBu") # get the colors

colornum <- cut(rank(plotvar), nclr, labels=FALSE)

colcode <- plotclr[colornum] # assign color

# scatter plot

plot.angle <- 45

scatterplot3d(orstationc$lon, orstationc$lat, plotvar, type="h", angle=plot.angle, color=colcode, pch=20, cex.symbols=2,

col.axis="gray", col.grid="gray")

```

The z-variable, in this case, annual precipitation, is plotted as a dot, and for interpretability a drop line is plotted below the dot. This simple addition facilitates finding the location of each point (where it hits the x-y, or latitude-longitude plane), as well as the value of annual precipitation.

Maps can be added to the 3-D scatter plot to improve interpretability:

```{r plot7}

library(maps)

# get points that define Oregon county outlines

or_map <- map("county", "oregon", xlim=c(-125,-114), ylim=c(42,47), plot=FALSE)

# get colors for labeling the points

plotvar <- orstationc$pann # pick a variable to plot

nclr <- 8 # number of colors

plotclr <- brewer.pal(nclr,"PuBu") # get the colors

colornum <- cut(rank(plotvar), nclr, labels=FALSE)

colcode <- plotclr[colornum] # assign color

# scatterplot and map

plot.angle <- 135

s3d <- scatterplot3d(orstationc$lon, orstationc$lat, plotvar, type="h", angle=plot.angle, color=colcode,

pch=20, cex.symbols=2, col.axis="gray", col.grid="gray")

s3d$points3d(or_map$x,or_map$y,rep(0,length(or_map$x)), type="l")

```

The `map()` function generates the outlines of a map of Oregon counties, and stores them in `or.map`, then the colors are figured out, and finally a 3-D scatter plot is made (using the `scatterplot3d()` function, and finally a 3-D scatter plot is made (using the scatterplot3d() function, and the points and droplines are added.

[[Back to top]](lec05.html)

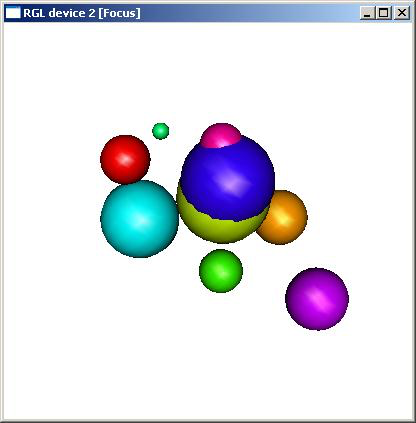

# OpenGL surface and point plots #

The `rgl` package (by D. Alder and Duncan Murdoch) can be used to plot points (and surfaces and lines) in a 3-D space. The main feature that distinguishes this approach is the ability to rotate the cloud of points "on the fly." Here’s what the code looks like, and when the image appears, it can be rotated and spun by dragging the mouse within the window. Holding down the left button while dragging rotates the balls, while holding down the right changes the perspective.

```{r rgl1, echo=TRUE, eval=FALSE, results='hide', message=FALSE}

library(rgl)

example(rgl.surface)

rgl.clear()

example(rgl.spheres)

```

[[Back to top]](lec05.html)

# Trellis/Lattice graphics #

Many data sets include a mixture of both "continuous" (ordinal-, interval- or ratio-scale variables) and "discrete" (nominal-scale variables). Often, the issue might arise of how a particular relationship between variables might differ among groups. Information of that nature can be gained using conditioning plots (or coplots). Such plots are part of a general scheme of visual data analysis, known as Trellis Graphics that has been created by the developers of the S language. Trellis Graphics are implemented in R using the package Lattice.

## Coplots (conditioning scatter plots) ##

Conditioning scatter plots involves creating a multipanel display, where each panel contains a subset of the data. This subset can be either a) those observations that fall in a particular group, or b) they may represent a the values that fall within a particular range of the values of a variable. The idea is that the individual panels should illustrate the relationship between a pair of variables, over part of the range of the two marginal "conditioning" variables (i.e. the relationship "conditional on one marginal variable lying in one particular interval, and the other lying in a different interval.")

This coplot contains scatter diagrams for Yes as a function of the log(10) of Population, conditioned by country (i.e. one "response" variable and one "conditioning" variable.)

```{r plot16}

library(lattice)

attach(scanvote)

coplot(Yes ~ log10(Pop) | Country, columns=3,

panel=function(x,y,...) {

panel.smooth(x,y,span=.8,iter=5,...)

abline(lm(y ~ x), col="blue") }

)

```

Note the use of the "panel" function here. Basically, what's going on is that the `coplot()` function is determining which subset of observations should appear in each panel, while the two function calls within the `panel()` function (`panel.smooth()` and `abline()`) perform their tasks on that subset of observations. In other words, `coplot()` selects the observations of `Yes` and `log(Pop)` for a particular panel (i.e. `Country`), sends these to the panel function, which passes them on (relabeled as x and y), and plots the points, and then `panel.smooth()` and `albline()` draw a lowess curve and least-squares line for those observations on each panel (more about those later). The general idea is to compare the panels (countries) seeing where in the panel the points lie and what the relationship looks like. The general relationship between population and percent of `Yes` votes is apparent, as well as country-to-country differences, like the generally greater proportion of `Yes` votes in Finland.

```{r}

detach(scanvote)

```

## Coplot, conditioning by one continuous numeric variable ##

Most of the time, the conditioning variables are continuous numeric variables. Here's a coplot for `WidthWS` as a function of `DepthWS` in the Summit Cr. data set, conditioned by `CumLen` (or distance downsteam):

```{r plot17, messages=FALSE}

attach(sumcr)

coplot(WidthWS ~ DepthWS | CumLen, pch=14+as.integer(Reach), cex=1.5,

number=3, columns=3,

panel=function(x,y,...) {

panel.smooth(x,y,span=.8,iter=5,...)

abline(lm(y ~ x), col="blue")

}

)

```

We know the arrangement of the reaches, and so the resulting plot should be no surprise. The plotting characters are determined by Reach, to reveal the extent of overlap in the conditioning "shingles." The plot could be regenerated using Reach as the conditioning variable, which would result in no overlap between the individual panels.

It’s easy to see that the two grazed reaches (A upstream and C downstream) have generally wider channels, which would be expected. Something that is not apparent in ordinary plots of the data is that the "normal" or expected inverse relationship between width and depth (as one gets bigger the other gets smaller) does not apply in the middle (exclosure) reach.

```{r}

detach(sumcr)

```

[[Back to top]](lec05.html)

# More Lattice Plots #

"Trellis" plots are the R version of Lattice plots that were originally implemented in the S language at Bell Labs. The aim of these plots is to extend the usual kind of univariate and bivariate plots, like histograms or scatter plots, to situations where some external variables, possibly categorical or "factor" variables, may influence the distribution of the data or form of a relationship. They do this by generating a trellis or lattice of plots that consist of an array of simple plots, arranged according to the values of some "conditioning" variables.

## Multipanel plots ##

A multipanel plot, in which the individual panels are "conditioned" by the value of a third variable, here longitude, can be illustrated for the Oregon climate station data using the following script:

```{r plot18, messages=FALSE, warnings=FALSE}

library(lattice)

attach(orstationc)

```

```{r}

# make a factor variable indicating which longitude band a station falls in

Lon2 <- equal.count(lon,8,.5)

# plot the lattice plot

plot1 <- xyplot(pann ~ elev | Lon2,

layout = c(4, 2),

panel = function(x, y) {

panel.grid(v=2)

panel.xyplot(x, y)

panel.loess(x, y, span = 1.0, degree = 1, family="symmetric")

panel.abline(lm(y~x))

},

xlab = "Elevation (m)",

ylab = "Annual Precipitation (mm)"

)

print(plot1, position=c(0,.375,1,1), more=T)

# add the shingles

print(plot(Lon2), position=c(.1,0.0,.9,.4))

detach(orstationc)

```

The idea here is to chop longitude into eight bands from west to east using the equal.count() function. (The third argument here, 0.5, indicates that the bands should overlap by 50 percent.) Then the lattice plot is made using the xyplot() function, which makes a separate scatter plot for each longitude band, showing the relationship between annual precipitation and elevation. A "shingles" plot is added at the bottom to indicate the range of longitudes that go into each plot.

Notice that in each panel, a straight regression line (more about regression later) and a smooth lowess curve have been added to help summarize the relationships. The panels are arranged in longitudinal order from low (west) to high (east, remember that in the western hemisphere, longitudes are negative). The plots are certainly interesting. The general idea is that precipitation should increase with increasing elevation, but at least for the western part of the state the reverse seems to be true! What is going on here is that proximity to the Pacific is a much more important control than elevation, and low elevation coastal and inland stations are quite wet. In the eastern part of the state (top row of panels), the expected relationship holds, but it's kind of hard to see because the wet western part of the state stretches out the scale.,

The following plots explore the seasonality of precipitation in the Yellowstone region. This first plot uses glyphs to show the values of twelve monthly precipitation variables as "spokes" of a wheel, where each variable is plotted relative to its overall range. The first block of code below sets things up, and the `stars()` function does the plotting.

```{r plot19}

library(sf)

attach(yellpratio)

# simple map

# read and plot shapefiles

ynp_state_sf <- st_read("/Users/bartlein/Documents/geog495/data/shp/ynpstate.shp")

plot(st_geometry(ynp_state_sf))

ynprivers_sf <- st_read("/Users/bartlein/Documents/geog495/data/shp/ynprivers.shp")

plot(st_geometry(ynprivers_sf), add = TRUE)

ynplk_sf <- st_read("/Users/bartlein/Documents/geog495/data/shp/ynplk.shp")

plot(st_geometry(ynplk_sf), add = TRUE)

points(Lon, Lat, pch=3, cex=0.6)

# stars plot for precipitation ratios

col.red <- rep("red",length(orstationc[,1]))

stars(yellpratio[,4:15], locations=as.matrix(cbind(Lon, Lat)),

col.stars=col.red, len=0.2, lwd=1, key.loc=c(-111.5,42.5), labels=NULL, add=T)

```

Here the stars wind up looking more like fans. The legend indicates that stations with fans that open out to the right are stations with winter precipitation maxima (like in the southwestern portion of the region) while those that open toward the left have summer precipitation maxima (like in the southeastern portion of the region).

The next examples show a couple of conditioning plots (coplots), that illustrate the relationship between January and July precipitation, as varies (is conditioned on) with elevation. The first block of code does some set up.

```{r plot20}

# create some conditioning variables

Elevation <- equal.count(Elev,4,.25)

Latitude <- equal.count(Lat,2,.25)

Longitude <- equal.count(Lon,2,.25)

# January vs July Precipitation Ratios by Elevation

plot2 <- xyplot(APJan ~ APJul | Elevation,

layout = c(2, 2),

panel = function(x, y) {

panel.grid(v=2)

panel.xyplot(x, y)

panel.loess(x, y, span = 1.0, degree = 1, family="symmetric")

panel.abline(lm(y~x))

},

xlab = "APJul",

ylab = "APJan")

print(plot2, position=c(0,.375,1,1), more=T)

print(plot(Elevation), position=c(.1,0.0,.9,.4))

```

The plot shows that the relationship between January and July precipitation indeed varies with elevation. At low elevations, there is proportionally lower January precipitation for the same July values (lower two panels on the lattice plot), but at higher elevations, there is proportionally more (top two panels). This relationship points to some orographic (i.e. related to the elevation of the mountains) amplification of the winter precipitation.

The next plot shows the variation of the relationship between January and July precipitation as it varies spatially.

```{r plot21}

# January vs July Precipitation Ratios by Latitude and Longitude

plot3 <- xyplot(APJan ~ APJul | Latitude*Longitude,

layout = c(2, 2),

panel = function(x, y) {

panel.grid(v=2)

panel.xyplot(x, y)

panel.loess(x, y, span = .8, degree = 1, family="gaussian")

panel.abline(lm(y~x))

},

xlab = "APJul",

ylab = "APJan")

print(plot3)

```

Notice that the steepest curve lies in the panel representing the southwestern part of the region (low latitude and low longitude, i.e. the bottom left panel), which suggests that winter (January) precipitation is relatively more import there, which is also apparent on the stars plot above.

Next, the general idea that seems to be emerging, that there variations within the region of the relative importance of summer and winter precipitation can be explored by a parallel-coordinate plot, that allow different precipitation "regimes" to be detected by the appearance of distinct "bundles" of curves.

```{r plot22}

# Parallel plot of precipitation ratios

plot4 <- parallelplot(~yellpratio[,4:15] | Elevation,

layout = c(4, 1),

ylab = "Precipitation Ratios")

print(plot4)

```

Notice that at low elevations, most of the stations are behaving similarly, and showing a distinct summer precipitation maximum (and only one station seems to show a winter maximum). At high elevations, there is more variability but a general tendency for winter precipitation to dominate.

Lattice plots can extend many of the basic univariate and bivariate plots. For example, a set of scatter plot matrices can be generated, for the high/low latitude and longitude slices.

```{r plot23}

# Lattice plot of scatter plot matrices

plot5 <- splom(~cbind(APJan,APJul,Elev) | Latitude*Longitude)

print(plot5)

```

```{r}

detach(yellpratio)

```

These plots provide a different prospective on the variations of precipitation across the region, but they're consistent with what the other plots show.

# Lattice-like plots of maps (using ggplot()) #

The `ggplot2` package can produce lattice-like multipanel plots, by "faceting", and for spatial data provides an alternative to `spplot` in the spatial (`sp`) package. Ploting with `ggplot2` will be the focus of an upcoming lecture.

The following example uses a data set of locations and elevations Oregon cirque basins (upland basins eroded by glaciers), and whether or not they are currently (early 21st century) glaciated. Whether a cirque is occupied by a glacier or not is basically determined by the trade-off between snow accumulation (and hence winter precipitation) and summer ablation (or melting, and hence summer temperature. Cirque basins not currently occupied by glaciers were, of course, occupied in the past, while those occupied today indicate where "glacier-safe" climate prevails (at least for now).

In the code below, the two `as.factor()` functions are used to turn the single variable `cirques_sf$Glacier`, which has the values "`G`" and "`U`", into two "binary" (0 or 1) variables. The variable `cirques_sf$Glaciated` will contain 1's for glaciated cirques, and 0 otherwise (i.e. unglaciated cirques), while the variable `cirques_sf$Unglaciated` will contain 1's for unglaciated cirques, and 0 otherwise. The two variables are obviously redundant (the elements would sum to 1 for each observation), but it makes the illustration of the method more transparent.

```{r plot24}

# load the ggplot2 package

library(ggplot2)

```

```{r}

# multi-panel lattice plot

cirques_sf$Glaciated <- ifelse(cirques_sf$Glacier=="G",1,0)

cirques_sf$Unglaciated <- ifelse(cirques_sf$Glacier=="U",1,0)

```

Use the `ggplot()` function in the `ggplot2` package (note the name distinction), to produce simple map of cirque locations.

```{r ggplot 1}

ggplot() +

geom_sf(data = orotl_sf) +

geom_point(aes(cirques_sf$Lon, cirques_sf$Lat), size = 2.0 , color = cirques_sf$Glaciated + 1) +

labs(x = "Longitude", y = "Latitude") +

theme_bw()

```

It's pretty easy to see where the glaciated cirques occur.

Here are two multi-panel plots constructed using "facets", the first plotting separate maps for glaciated and unglaciated cirques, and the second plotting cirques by region.

```{r ggplot 2}

ggplot(cirques_sf) +

geom_sf(data = orotl_sf) +

geom_point(aes(Lon, Lat), size = 1.0 , color = cirques_sf$Glaciated + 1) +

facet_wrap(~Glacier) +

labs(x = "Longitude", y = "Latitude") +

theme_bw()

ggplot(cirques_sf) +

geom_sf(data = orotl_sf) +

geom_point(aes(Lon, Lat), size = 1.0 , color = cirques_sf$Glaciated + 1) +

facet_wrap(~Region) +

labs(x = "Longitude", y = "Latitude") +

theme_bw()

```

This way of mapping the cirques could also have been done by plotting a simple shape file, and then putting points on top, e.g.

```{r plot25}

plot(st_geometry(orotl_sf))

points(cirques_sf$Lon, cirques_sf$Lat, col=3-as.integer(cirques_sf$Glacier))

legend(-118, 43.5, c("Glaciated","Unglaciated"), pch=c(1,1), col=c(2,1))

```

[[Back to top]](lec05.html)

# Readings #

- Kuhnert & Venebles (*An Introduction...*): p. 86-96, 179-201;

- Rossiter (*Introduction ... ITC*): sections 5.1 and 5.2.

- Peng (*EDA with R*): Ch. 10

- Chang (*R Graphics Cookbook*): Ch. 11, 12, 13

The main documentation for Trellis graphics includes:

- [Trellis Graphics User Manual](https://pjbartlein.github.io/GeogDataAnalysis/pdfs/trellisuser.pdf), and

- [A Tour of Trellis Graphics](https://pjbartlein.github.io/GeogDataAnalysis/pdfs/Trellis_tour.pdf)

two .pdf documents published by the developers of the S language and Trellis Graphics, Lucent Technology.