Table of Contents

- 0. Before we start

- 1. Introduction or Golang (Go) in a Nutshell

- 2. Basic

- 3. Functions

- 4. Packages

- 5. Pointer

- 6. Allocation & Constructor

- 7. Conversions

- 8. Interfaces

- 9. Concurrency

- 10. Communication

- 11. Modules (Golang version >=1.11)

- 12. Data IO in Go

- 13. Encoding & Decoding

- 14. Web Programming

- 15. Remote Procedure Call (RPC), gRPC and protobuf

- 16. New packages

- Resource for new Go programmers

Finding Golang documentation isn't a big deal. There are many good resources, just choose one & start your learning journey. I mainly follow Learning Go - Miek Gieben.

NOTE: Every examples in this documentation are stored in directories named by section. I assume that every commands in section X will be executed in example/X directory, so I don't write a full path to Go script file.

- An open source programming language supported by Google.

- Imperative language

- Statically typed

- Compile to native code (no JVM)

- Syntax tokens similar to C (bu tless parentheses and no semicolors) and the structure to Oberon-2

- Is Go an object-oriented language?: Yes and no

- Has types and methods and allows an object-oriented style of programming, there is no type hierarchy (There's type embedding, though).

- No classes, but structs with methods.

- Interfaces

- Functions - Methods are first class citizens:

- Methods are more general than Java or C++: they can be defined for any sort of data, even built-in types such as plain, "unboxes" integers. They are not restricted to structs (classes).

- Methods can return multiple values.

- Has closures

- Pointers, but not pointer arithmetic

- Built-in concurrency primitives: Goroutines and Channels

- Get started with Go in the classic way: printing "Hello World" (Ken Thompson & Dennies Ritchie started this when they presented the C language in the 1970s #til)

/* hello_world.go */

package main

import "fmt" // Implements formatted I/O

/* Say Hello-World */

func main() {

fmt.Printf("Hello World")

}- To build helloworld.go, just type:

go build helloworld.go # Return an executable called helloworld- Run a previous step result

./helloworld- Want to ombine these two steps? Ok, Golang got you.

go run helloworld.go- Go is different from most other language in that type of a variable is specified after the variable name: a int.

/* When you declare a variable it is assigned the "natural" null value for the type */

var a int // a has a value of 0

var s string // s is assigned the zero string, which is ""

a = 26

s = "hello"

/* Declaring & assigning in Go is a two step process, but they may be combined */

a := 26 // In this case the variable type is deduced from the value. A value of 26 indicates an int for example.

b := "hello" // The type should be string

/* Multiple var declarations may also be grouped (import & const also allow this) */

var (

a int

b string

)

/* Multiple variables of the same type ca also be declared on a single line */

var a, b int

a, b := 26, 9

/* A special name for a variable is _, any value assigned to it is discarded. */

_, b := 26, 9-

Boolean:

bool -

Numerical:

- Go has most of the well-know types such as

int- it has the appropriate length for your machine (32-bit machine - 32 bits, 64-bit machine - 64 bits) - The full list for (signed & unsigned) integers is

int8,int16,int32,int64&byte(an alias foruint8),uint8,uint16,uint32,uint64. - For floating point values there is

float32,float64,float.

/* numerical_types.go */ package main func main() { var a int var b int32 b = a + a // Give an error: cannot use a + a (type int) as type int32 in assignment. b = b + 5 }

- Go has most of the well-know types such as

-

Constants: Constants are created at compile time, & can only be numbers, strings, or booleans. You can use

iotato enumerate values.

const (

a = iota // First use of iota will yield 0. Whenever iota is used again on a new line its value is incremented with 1, so b has a vaue of 1.

b

)-

Strings:

- Strings in Go are a sequence of UTF-8 characters enclosed in double quotes. If you use the single quote you mean one character (encoded in UTF-8) - which is not a

stringin Go. Note that! In Python (my favourite programming language), I can use both of them for string assignment. - String in Go are immutable. To change one character in string, you have to create a new one.

s1 := "Hello" c := []rune(s) // Convert s1 to an array of runes c[0] := 'M' s2 := string(c) // Create a new string s2 with the alteration fmt.Printf("%s\n", s2)

- Strings in Go are a sequence of UTF-8 characters enclosed in double quotes. If you use the single quote you mean one character (encoded in UTF-8) - which is not a

-

Rune:

Runeis an alias forint32, (use when you're iterating over characters in a string). -

Complex Numbers:

complex128(64 bit real & imaginary parts) orcomplex32. -

Errors: Go has a builtin type specially for errors, called

error.var e. -

Go 1.18 brings support for Generic types. The generics implementation provided by Go 1.18 follows the type parameter proposal and allows developers to add optional type parameters to type and function declarations. Checkout Golang's generics tutorial.

package main

import "fmt"

type Number interface {

int64 | float64

}

func main() {

// Initialize a map for the integer values

ints := map[string]int64{

"first": 34,

"second": 12,

}

// Initialize a map for the float values

floats := map[string]float64{

"first": 35.98,

"second": 26.99,

}

fmt.Printf("Non-Generic Sums: %v and %v\n",

SumInts(ints),

SumFloats(floats))

fmt.Printf("Generic Sums: %v and %v\n",

SumIntsOrFloats[string, int64](ints),

SumIntsOrFloats[string, float64](floats))

fmt.Printf("Generic Sums, type parameters inferred: %v and %v\n",

SumIntsOrFloats(ints),

SumIntsOrFloats(floats))

fmt.Printf("Generic Sums with Constraint: %v and %v\n",

SumNumbers(ints),

SumNumbers(floats))

}

// SumInts adds together the values of m.

func SumInts(m map[string]int64) int64 {

var s int64

for _, v := range m {

s += v

}

return s

}

// SumFloats adds together the values of m.

func SumFloats(m map[string]float64) float64 {

var s float64

for _, v := range m {

s += v

}

return s

}

// SumIntsOrFloats sums the values of map m. It supports both floats and integers

// as map values.

func SumIntsOrFloats[K comparable, V int64 | float64](m map[K]V) V {

var s V

for _, v := range m {

s += v

}

return s

}

// SumNumbers sums the values of map m. Its supports both integers

// and floats as map values.

func SumNumbers[K comparable, V Number](m map[K]V) V {

var s V

for _, v := range m {

s += v

}

return s

}- Go supports the normal set of numerical operators.

Precedence Operator(s)

Highest * / % << >> & &^

`+ -

== != < <= > >=

<-

&&

Lowest ||

&bitwise and,|bitwise or,^bitwise xor,&^bit clear respectively.

break default func interface select

case defer go map struct

chan else goto package switch

const fallthrough if range type

continue for import return var

var,const,package,importare used in the previous sections.funcis used to declare functions & methods.returnis used to return from functions.gois used for concurrency.selectis used to choose from different types of communication.interface.structis used for abstract data types.type.

- If-Else:

if x > 0 {

return y

} esle {

return x

}

if err := MagicFunction(); err != nil {

return err

}

// do something- Goto: With

gotoyou jump to a label which must be defined within the current function.

/* goto_test */

/* Create a loop */

func gototestfunc() {

i := 0

Here:

fmt.Println()

i++

goto Here

}- For:

forloop has three forms, only one of which has semicolons:

for init; condition; post { } // aloop using the syntax borrowed from C

for condition { } // a while loop

for { } // a endless loop

sum := 0

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

sum = sum + i

}- Break & continue:

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i > 5 {

break

}

fmt.Println(i)

}

/* With loops within loop you can specify a label after `break` to identify which loop to stop */

J: for j := 0; j < 5; j++ {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i > 5 {

break J

}

fmt.Println(i)

}

}-

Range:

rangecan be used for loops. It can loop over slices, arrays, strings, maps & channels.rangeis an iterator that, when called, returns the next key-value pair from the "thing" it loops over.

list := []string{"a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f"} for k, v := range list { // do some fancy thing with k & v }

-

Switch:

- The case are evaluated top to bottom until a match is found, & if the

switchhas no expression it switches ontrue. - It's therefore possible - & idomatic - to write an

if-else-if-elsechain as aswitch.

/* Convert hexadecimal character to an int value */ switch { // switch without condition = switch true case '0' <= c && c <= '9': return c - '0' case 'a' <= c && c <= 'f': return c - 'a' + 10 case 'A' <= c && c <= 'F': return c - 'A' + 10 } return 0 /* Automatic fall through */ switch i { case 0: fallthrough case 1: f() default: g() }

- The case are evaluated top to bottom until a match is found, & if the

close new panic complex

delete make recover real

len append print imag

cap copy println

- close: is used in channel communication. It closes a channel (obviously XD)

- delete: is used for deleting entries in maps.

- len & cap: are used on a number of different types,

lenis used to return the lengths of strrings, maps, slices & arrays. - new: is used for allocating memory for user defined data types.

- copy, append:

copyis for copying slices. Andappendis for concatenating slices. - panic, recover: are used for an exception mechanism.

- complex, real, imag: all deal with complex numbers.

-

Brief: list -> arrays, slices. dict -> map

-

Arrays:

- An array is defined by

[n]<type>.

var arr [10]int // The size is part of the type, fixed size arr[0] = 42 arr[1] = 13 fmt.Printf("The first element is %s\n", arr[0]) // Initialize an array to something other than zero, using composite literal a := [3]int{1, 2, 3} a := [...]int{1, 2, 3}

- Array are value types: Assigning one array to another copies all the elements. In particular, if you pass an array to a function it will receive a copy of the array, not a pointer to it. To avoid the copy you could pass a pointer to the array, but then that's a pointer to an array, not an array.

- An array is defined by

-

Slices:

- Similar to an array, but it can grow when new elements are added.

- A slice is a pointer to an (underlaying) array, slices are reference types.

// Init array primes primes := [6]int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13} // Init slice s var s []int = primes[1:4] fmt.Println(s) // Return [3, 5, 7] /* slice_length_capacity.go */ package main import "fmt" func main() { s := []int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13} printSlice(s) // Slice the slice to give it zero length. s = s[:0] printSlice(s) // Extend its length. s = s[:4] printSlice(s) // Drop its first two values. s = s[2:] printSlice(s) } func printSlice(s []int) { fmt.Printf("len=%d cap=%d %v\n", len(s), cap(s), s) }

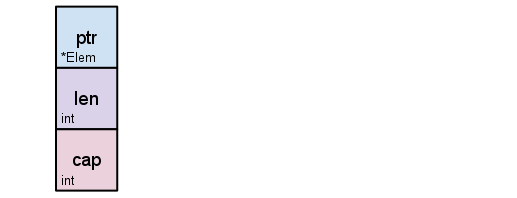

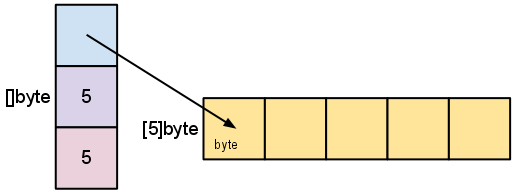

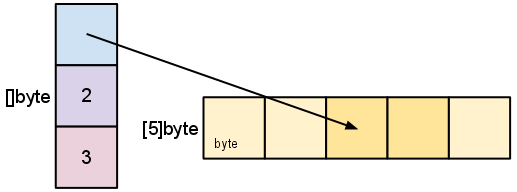

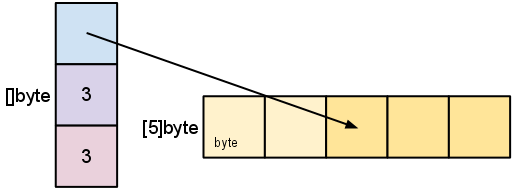

- A slice is a descriptor of an array segment. It consists of a pointer to the array, the length of the segment & its capacity (the maximum length of the segment).

s := make([]byte, 5)

-

lenis the number of elements referred to by the slice. -

capis the number of elements in the underlying array (beginning at the element referred to by the slice pointer).s = s[2:4]

-

Slicing does not copy the slice's data. It creates a new slice that points to the original array. This makes slice operations as efficient as manipulating array indicies. Therefore, modifying the elements (not the slice itself) of a re-slice modifies the elements of the original slice:

d := []byte{'r', 'o', 'a', 'd'} e := d[2:] // e = []byte{'a', 'd'} e[1] = 'm' // e = []byte{'a', 'm'} // d = []byte{'r', 'o', 'a', 'm'}

- Earlier we sliced

sto a length shorter than its capacity. We can grow s to its capacity by slicing it again.

s = s[:cap(s)]

- Earlier we sliced

-

-

A slice cannot be grown beyond its capacity.

// Another example var array [m]int slice := array[:n] // len(slice) == n // cap(slice) == m // len(array) == cap(array) == m

- To extend a slice, there are a couple of built-in functions that make life easier:

append©.

s0 := []int{0, 0} s1 := append(s0, 2) // same type as s0 - int. // If the original slice isn't big enough to fit the added values, // append will allocate a new slice that is big enough. So the slice // returned by append may refer to a different underlaying array than // the original slices does. s2 := append(s1, 3, 5, 7) s3 := append(s2, s0...) // []int{0, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 0, 0} - three dots used after s0 is needed make it clear explicit that you're appending another slice, instead of a single value var a = [...]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7} var s = make([]int, 6) // copy function copies slice elements from source to a destination // returns the number of elements it copied n1 := copy(s, a[0:]) // n1 = 6; s := []int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5} n2 := copy(s, s[2:]) // n2 = 4; s := []int{2, 3, 4, 5, 4, 5}

-

Maps:

- Python has its dictionaries. In go we have the

maptype.

monthdays := map[string]int{ "Jan": 31, "Feb": 28, "Mar": 31, "Apr": 30, "May": 31, "Jun": 30, "Jul": 31, "Aug": 31, "Sep": 30, "Oct": 31, "Nov": 30, "Dec": 31, // A trailing comma is required } value, key := monthdays["Jan"]

- Use

makewhen only declaring a map. A map is reference type. A map is not reference variable, its value is a pointer to aruntime.hmapstructure.

- Python has its dictionaries. In go we have the

- There are no classes, only structs. Structs can have methods:

// A struct is a type. It's also a collection of fields

// Declaration

type Vertex struct {

X, Y float64

}

// Creating

var v = Vertex{1, 2}

var v = Vertex{X: 1, Y: 2} // Creates a struct by defining values with keys

var v = []Vertex{{1,2},{5,2},{5,5}} // Initialize a slice of structs

// Accessing members

v.X = 4

// You can declare methods on structs. The struct you want to declare the

// method on (the receiving type) comes between the the func keyword and

// the method name. The struct is copied on each method call(!)

func (v Vertex) Abs() float64 {

return math.Sqrt(v.X*v.X + v.Y*v.Y)

}

// Call method

v.Abs()

// For mutating methods, you need to use a pointer (see below) to the Struct

// as the type. With this, the struct value is not copied for the method call.

func (v *Vertex) add(n float64) {

v.X += n

v.Y += n

}- Anonymous structs: cheaper & safer than using

map[string]intefaces. - You can check Defining your own types for more.

- There is no subclassing in Go. Instead, there is interface and struct embedding.

// ReadWriter implementations must satisfy both Reader and Writer

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}

// Server exposes all the methods that Logger has

type Server struct {

Host string

Port int

*log.Logger

}

// initialize the embedded type the usual way

server := &Server{"localhost", 80, log.New(...)}

// methods implemented on the embedded struct are passed through

server.Log(...) // calls server.Logger.Log(...)

// the field name of the embedded type is its type name (in this case Logger)

var logger *log.Logger = server.Logger// General Function

type mytype int

func (p mytype) funcname(q, int) (r, s int) { return 0,0 }

// p (optional) bind to a specific type called receiver (a function with a receiver is usually called a method)

// q - input parameter

// r,s - return parameters- Functions can be declared in any order you wish.

- Go does not allow nested functions, but you can work around this with anonymous functions.

- Variables declared outside any functions are global in Go, those defined in functions are local to those functions.

- If names overlap - a local variable is decleard with the same name as a global one - the local variable hides the global one when the current function is executed.

- As with almost everything in Go, functions are also just values.

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := func() { // a is defined as an anonymous (nameless) function,

fmt.Println("Hello")

}

a()

}func printit(x int) {

fmt.Println("%v\n", x)

}

func callback(y int, f func(int)) {

f(y)

}/* Open a file & perform various writes & reads on it. */

func ReadWrite() bool {

file.Open("file")

// Do your thing

if failureX {

file.Close()

return false

}

// Repeat a lot of code.

if failureY {

file.Close()

return false

}

file.Close()

return true

}

/* Same situation but using defer */

func ReadWrite() bool {

file.Open("file")

defer file.Close() // add file.Close() to the defer list

// Do your thing

if failureX {

return false

}

if failureY {

return false

}

return true

}- Can put multiple functions on the "defer list".

Deferfunctions are executed in LIFO order.

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

defer fmt.Printf("%d ", i) // 4 3 2 1 0

}- With

deferyou can even change return values, provided that you are using named result parameters & a function literal (def func(x int) {/*....*/}(5)).

func f() (ret int)

defer func() { // Initialized with zero

ret++

}()

return 0 // This will not be the returned value, because of defer. Ths function f will return 1

}- Functions that take a variable number of parameters are known as variadic functions.

func func1(arg... int) { // the variadic parameter is just a slice.

for _, n := range arg {

fmt.Printf("And the number is: %d\n", n)

}

}- Go does not have an exception mechanism: you can not throw exception. Instead it uses a panic & recover mechanism.

- Panic: Built-in function that tstops the oridinary flow of control & begins panicking. When function F call

pacnic, execution ofFstops, any deferred functions in F are executed normally, & then F returns to its caller. To the caller, F then behaves like a call to panic. The process continues up the stack until all functions in the current goroutine have returned, at which point the program crashes. Panics can be initiated by invoking panic directly. They can also be caused by runtime errors, such as out-of-bounds array accesses. - Recover: Built-in function that regains control of a panicking goroutine. Recover is only useful inside deferred functions. During normal execution, a call to recover will return nil & have no other effect. If the current goroutine is panicking, a call to recover will capture the value given to panic & resume normal execution.

- Panic: Built-in function that tstops the oridinary flow of control & begins panicking. When function F call

/* defer_panic_recover.go */

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

f()

fmt.Println("Returned normally from f.")

}

func f() {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered in f", r)

}

}()

fmt.Println("Calling g.")

g(0)

fmt.Println("Returned normally from g.")

}

func g(i int) {

if i > 3 {

fmt.Println("Panicking!")

panic(fmt.Sprintf("%v", i))

}

defer fmt.Println("Defer in g", i)

fmt.Println("Printing in g", i)

g(i + 1)

}

/* Result */

// Calling g.

// Printing in g 0

// Printing in g 1

// Printing in g 2

// Printing in g 3

// Panicking!

// Defer in g 3

// Defer in g 2

// Defer in g 1

// Defer in g 0

// Recovered in f 4

// Returned normally from f.- Still don't understanding how these works? Don't worry, I got you. Check Go Defer Simplified with Praticial Visuals by Inanc Gunmus.

- Other useful links about Defer:

- Check out use cases

- To handle panics gracefully, check handle tips.

- A package is a collection of functions & data.

- The convention for package names is to use lowercase characters - the file does not have to match the package name.

package even

func Even(i int) bool { // starts with capital -> exported

return i%2 == 0

}

func odd(i int) bool { // start with lower-case -> private

return i%2 == 1

}- Build the package

mkdir $GOPATH/src/even

cp even.go $GOPATH/src/even

go build

go install- Now you can use the package in your program with

import "even".

- The Convention in Go is to use CamelCase rather than underscores to write multi-word names.

- The Convention in Go is that package names are lowercase, single word names.

- Override default package name:

import bar "bytes". - Another convention is that the package name is the base name of its source directory; the package in

src/compress/gzipis imported ascompress/gzipbut has namegzip, notcompress/gzip. - Avoid stuttering when naming things.

- The function to make new instance of

ring.Ringpackage (packagecontainer/ring), would normally be calledNewRing, but sinceRingis the only type exported by the package, since the package is calledring, it's called justNew. Clients of the package see that asring.New.

- Each package should have a package comment**.

- When a package consists of multiple files the package comment should only appear in 1 file.

- A common convention (in really big packages) is to have a separate

doc.gothat only holds the package comment.

/*

The regexp package implements a simple library for

regular expressions.

The syntax of the regular expressions accepted is:

regexp:

concatenation { '|' concatenation }

*/

package regexp- Each defined (and exported) function should have a same line of text documenting the behavior of the function.

- There are two types of packages: An executable package (main application since you will be running it) & an utility package (is not self executable, instead it enhances functionality of an executable package by providing utility functions & other import assets).

- Go exports a variable if a variable name starts with Uppercase. All other variables not starting with an uppercase letter is private to the package.

- For an executable package, a file with

mainfunction is entry file for execution.

- Package scope - A scope is a region in code block where a defined variable is accessible. A package scope is a region within a package where a declared variable is accessible from within a package (across all files in the package). This region is the top-most block of any file in the package. You are not allowed to re-declare global variable with same name in the same package

- Variable initialization.

- Init function: Like

mainfunction,initfunction is called by Go when a package is initialized. It does not take any arguments & doesn’t return any value.initfunction is implicitly declared by Go. You can have multipleinitfunctions in a file or a package. Order of the execution ofinitfunction in a file will be according to the order of their appearances. - Package alias: Underscore is a special character in Go which act as

nullcontainer. - A main thing to remember is, an imported package is initialized only once per package. Hence if you have many import statements in a package, an imported package is going to be initialized only once in the lifetime of main package execution.

go run *.go

├── Main package is executed

├── All imported packages are initialized

| ├── All imported packages are initialized (recursive definition)

| ├── All global variables are initialized

| └── init functions are called in lexical file name order

└── Main package is initialized

├── All global variables are initialized

└── init functions are called in lexical file name orderInstalling a 3rd party package is nothing but cloning the remote code into local src/<package> directory. Unfortunately, Go does not support package version or provide package manager but a proposal is waiting here.

- Writing test involves the

testingpackage & the programgo test. - Source Golang writing unit tests

- Unit testing in Go is just a opinionated as any other aspect of the language like formatting or naming.

- Example:

package main

func Sum(x int, y int) int {

return x + y

}

func main() {

Sum(5, 5)

}

// Testcase

package main

import "testing"

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

total := Sum(5, 5)

if total != 10 {

t.Errorf("Sum was incorrect, got: %d, want: %d.", total, 10)

}

}- Test tables is a set (slice array) of test input & output values. Example:

package main

import "testing"

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

tables := []struct {

x int

y int

n int

}{

{1, 1, 2},

{1, 2, 3},

{2, 2, 4},

{5, 2, 7},

}

for _, table := range tables {

total := Sum(table.x, table.y)

if total != table.n {

t.Errorf("Sum of (%d+%d) was incorrect, got: %d, want: %d.", table.x, table.y, total, table.n)

}

}

}-

Launching tests:

- Within the same directory as the test, this picks up any files matching packagename_test.go:

go test- By fully-qualified package name:

go test github.com/username/package -

HTTP testing:

- The

net/http/httptestsub-package facilitates the testing automation of both HTTP server and client code. - When writing HTTP server code, you will undoubtedly run into the need to test your code in a robust and repeatable manner, without having to set up some fragile code harness to simulate end-to-end testing. Type

httptest.ResponseRecorderis designed specifically to provide unit testing capabilities for exercising the HTTP handler methods by inspecting state changes to the http.ResponseWriter in the tested function. - Creating test code for an HTTP client is more involved, since you actually need a server running for proper testing. Luckily, package

httptestprovides typehttptest.Serverto programmatically create servers to test client requests and send back mock responses to the client.

- The

-

Statement coverage: The

go testtool has built-in code-coverage for statements.

$ go test -cover

PASS

coverage: 50.0% of statements

ok github.com/alexellis/golangbasics1 0.009s

# Generate a HTML coverage report.

$ go test -cover -coverprofile=c.out

$ go tool cover -html=c.out -o coverage.html-

Code benchmark: The purpose of benchmarking is to measure a code's performance. The go test command-line tool comes with support for the automated generation and measurement of benchmark metrics. Similar to unit tests, the test tool uses benchmark functions to specify what portion of the code to measure.

-

Running the benchmark

$> go test -bench=. PASS BenchmarkVectorAdd-2 2000000 761 ns/op BenchmarkVectorSub-2 2000000 788 ns/op BenchmarkVectorScale-2 5000000 269 ns/op BenchmarkVectorMag-2 5000000 243 ns/op BenchmarkVectorUnit-2 3000000 507 ns/op BenchmarkVectorDotProd-2 3000000 549 ns/op BenchmarkVectorAngle-2 2000000 659 ns/op ok github.com/vladimirvivien/learning-go/ch12/vector 14.123s

-

Skipping test functions

> go test -bench=. -run=NONE -v PASS BenchmarkVectorAdd-2 2000000 791 ns/op BenchmarkVectorSub-2 2000000 777 ns/op Code Testing [ 314 ] ... BenchmarkVectorAngle-2 2000000 653 ns/op ok github.com/vladimirvivien/learning-go/ch12/vector 14.069s

-

Comparative benchmarks: to compare the performance of different algorithms that implement similar functionalities. Exercising the algorithms using performance benchmarks will indicate which of the implementations may be more compute and memory efficient.

-

-

Isolating dependencies: The Key factor that defines a unit test is isolation from runtime dependencies or collaborators. Check out Dependency Injection.

-

fmt: Package

fmtimplements formatted I/O with functions analogous to C'sprintf&scanf. The format verbs are derived from C's but are simpler. Some verbs (%-sequences) that can be used:- %v, the value in a default format, when printing structs, the plus flag (%+v) adds fields names.

- %#v, a Go-syntax representation of the value.

- %T, a Go-sytanx representation of the type of the value.

-

io: The package provides basic interfaces to I/O primitives. Its primary job is to wrap existing implementation of such primitives, such as those in package

os, into shared public interfaces that abstract the functionality, plus some other related primitives. -

bufio: This package implements buffered I/O. It wraps an io.Reader or io.Writer object, creating another object (Reader or Writer) that also implements the interface but provides buffering & some help for textual I/O.

-

sort: The sort package provides primitives for sorting arrays & user-defined collections.

-

strconv: The strconv package implements conversions to & from string representations of basic data types.

-

os: The os package provides a platform-independent interface to operating system functionality. The design is Unix-like.

-

sync: The package sync provides basic synchronization primitives such as mutual exclusion locks.

-

flag: The flag package implements command-line flag parsing.

-

encoding/json: The encoding/json package implements encoding & decoding of JSON objects as defined in RFC 4627.

-

html/template: Data-driven templates for generating textual output such as HTML.

-

net/http: The net/http package implements parsing of HTTP requests, replies, & URLs & provides an extensible HTTP server & a basic HTTP client.

-

unsafe: The unsafe package contains operations that step around the type safety of Go programs. Normally you don’t need this package, but it is worth mentioning that unsafe Go programs are possible.

-

reflect: The reflect package implements run-time reflection, allowing a program to manipulate objects with arbitrary types. The typical use is to take a value with static type interface{} & extract its dynamic type information by calling TypeOf, which returns an object with interface type Type.

-

os/exec: The os/exec package runs external commands.

-

Go has pointers but not pointer arthmetic, so they act more like references than pointers that you may know from C.

- A pointer is a variable which stores the address of another variable. A pointer is thus the location at which a value is stored. Not every value has an address but every variable does.

- A reference is a variable which refers to another value.

- There is no pointer arithmetic. You cannot write in Go. That is, you cannot alter the address p points to unless you assign another address to it.

var p *int p++

- Want to understand more? Check this article or another

this.

-

Pointers are useful. Remember that when you call a function in Go, the variables are pass-by-value. So, for efficiency & the possibility to modify a passed value in functions we have pointers.

-

Pointer type (* type) & address-of (&) operators *: If a variable is declared

var x int, the expression&x("address of x") yields a pointer to an integer variable (a value of type* int). If this value is calledp, we say "ppoints to tox", or equivalently "pcontains the address ofx". The variable to whichppoints is written*p. The expression*pyields the value of that variable, anint, but since*pdenotes a variable, it may also appear on the left-hand side of an assignment, in which case the assignment updates the variable. Reference herex := 1 p := &x // p, of type *int, points to x fmt.Println(*p) // "1" *p = 2 // equivalent to x = 2 fmt.Println(x) // "2"

-

All newly declared variables are assigned their zero value & pointers are no different. A newly declared pointer, or just a pointer that points to nothing, has a nil-value.

var p *int // declare a pointer

fmt.Printf("%v", p)

var i int

p = &i // Make p point to i

fmt.Printf("%v", p) // Print somthing like 0x7ff96b81c000a- Pointer illustration:

// Go program to illustrate the

// concept of the Pointer to Pointer

package main

import "fmt"

// Main Function

func main() {

// taking a variable

// of integer type

var V int = 100

// taking a pointer

// of integer type

var pt1 *int = &V

// taking pointer to

// pointer to pt1

// storing the address

// of pt1 into pt2

var pt2 **int = &pt1

fmt.Println("The Value of Variable V is = ", V)

fmt.Println("Address of variable V is = ", &V)

fmt.Println("The Value of pt1 is = ", pt1)

fmt.Println("Address of pt1 is = ", &pt1)

fmt.Println("The value of pt2 is = ", pt2)

// Dereferencing the

// pointer to pointer

fmt.Println("Value at the address of pt2 is or *pt2 = ", *pt2)

// double pointer will give the value of variable V

fmt.Println("*(Value at the address of pt2 is) or **pt2 = ", **pt2)

}

// The Value of Variable V is = 100

// Address of variable V is = 0x414020

// The Value of pt1 is = 0x414020

// Address of pt1 is = 0x40c128

// The value of pt2 is = 0x40c128

// Value at the address of pt2 is or *pt2 = 0x414020

// *(Value at the address of pt2 is) or **pt2 = 100- Check pointer vs reference.

-

Go also has garbage collection.

-

To allocate memory Go has 2 primitives,

new&make. -

new allocates; make initializes.

- new(T) returns *T pointing to a zerod T.

- make(T) returns an initialized T.

- make is only used for slices, maps, channels.

-

Constructors & compiste literals

// A lot of boiler plate

func NewFile(fd int, name string) *File {

if fd < 0 {

return nil

}

f := new(File)

f.fd = fd

f.name = name

f.dirinfo = nil

f.nepipe = 0

return f

}

// Using a composite literal

func NewFile(fd int, name string) *File {

if fd < 0 {

return nil

}

f := File{fd, name, nil. 0}

return &f // Return the address of a local variable. The storage associated with the variable survives after the function returns.

// return &File{fd, name, nil, 0}

// return &File{fd: fd, name: name}

}-

As a limiting case, if a composite literal contains no fields at all, it creates a zero value for the type. The expression

new(File)&&File{}are equivalent. -

Composite literal can also be created for arrays, slices, & maps, with the field labels being indices or map keys as appropriate.

ar := [...]string{Enone: "no error", Einval: "invalid argument"}

sl := []string{Enone: "no error", Einval: "invalid argument"}

ma := map[int]string {Enone: "no error", Einval: "invalid argument"}- Defining your own types

/* defining_own_type.go */

package main

import "fmt"

type NameAge struct {

name string // both non exported fiedls

age int

}

func main() {

a := new(NameAge)

a.name = "Kien"

a.age = 25

fmt.Printf("%v\n", a) // &{Kien, 25}

}- More on structure fields

struct {

x, y int

A *[]int

F func()

}-

Methods:

- Create a function that takes the type as an argument:

func doSomething1(n1 *NameAge, n2 int) {/* */} // method call var n *NameAge n.doSomething1(2)

- Create a function that works on the type:

func (n1 *NameAge) doSomething2(n2 int) {/* */}

NOTE: If x is addressable & &x's method set contains m, x.m() is shorthand for (&x).m().

- Suppose we have:

// A mutex is a data type with two methods, Lock & Unlock

type Mutex struct {/* Mutex fields */}

func (m *Mutex) Lock() {/* Lock impl */}

func (m *Mutext) Unlock {/* Unlock impl */}

// NewMutex is equal to Mutex, but it does not have any of the methods of Mutex.

type NewMutex Mutex

// PrintableMutex hash inherited the method set from Mutex, contains the methods

// Lock & Unlock bound to its anonymous field Mutex

type PrintableMutex struct{Mutex}FROM b []byte i []int r []rune s string f float32 i int

TO

[]byte . []byte(s)

[]int . []int(s)

[]rune []rune(s)

string string(b) string(i) string(r) .

float32 . float32(i)

int int(f) .

- float64 works the same as float32

- From a

stringto a slice of bytes or runes

mystring := "hello this is string"

byteslice := []byte(mystring)

runeslice := []rune(string)- From a slice of bytes or runes to a string

b := []byte{'h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'} // Composite literal

s := string(b)

i := []rune(26, 9, 1994)

r := string(i)-

For numeric values:

- Convert to an integer with a specific (bit) length:

uint8(int). - From floating point to an integer value:

int(float32). This discards the fraction part from the floating point value. - And other way around

float32(int)

- Convert to an integer with a specific (bit) length:

-

User defined types & conversions

type foo struct { int } // Anonymous struct field

type bar foo // bar is an alias for foo

var b bar = bar{1} // Declare `b` to be a `bar`

var f foo = b // Assign `b` to `f` --> Cannot use b (type bar) as type foo in assignment

var f foo = foo(b) // OK!- Every type has an interface, which is the set of methods defined for that type.

/* a struct type S with 1 field, 2 methods */

type S struct { i int }

func (p *S) Get() int { return p.i }

func (p *S) Put(v int) { p.i = v }

/* an interface type */

type I interface {

Get() int

Put() int

}

/* S is a valid implementation for interface I */- S is a valid implementation for ineterface I. A Go program can use this fact via yet another meaning of interface, which is an interface value:

func f(p I) {

fmt.Println(p.Get())

p.Put(1)

}

var s S

/* Because S implements I, we can call the

function f passing in a pointer to a value

of type S */

/* The reason we need to take the address of s,

rather than a value of type S, is because

we defined the methods on s to operae on pointers */

f(&s)-

The fact that you do not need to declare whether or not a type implements an interface means that Go implements a form of duck typing. This is not pure duck typing, because when possible the Go complier will statically check whether the type implements the inerface. However, Go does have a purely dynamic aspect, in that you can convert from one interface to another. In the general case, that conversion is checked at run time. If the conversion is invalid - if the type of the value stored in the existing interface value does not satisfy the interface to which it is being converted - the program will fail with a run time error.

- Duck typing - If it looks like a duck, & it quacks like a duck, then it is a duck. It means if it has a set of methods that match an interface, then you can use it wherever that interface is needed without explicitly defining that your types implement that interface.

package main import "fmt" type Duck interface { Quack() } type Donald struct { } func (d Donald) Quack() { fmt.Println("quack quack!") } type Daisy struct { } func (d Daisy) Quack() { fmt.Println("-quack -quack") } func sayQuack(duck Duck) { duck.Quack() } type Dog struct { } func (d Dog) Bark() { fmt.Println("go go") } func main() { donald := Donald{} sayQuack(donald) // quack daisy := Daisy{} sayQuack(daisy) // --quack dog := Dog() sayQuack(dog) // compile error - cannot use dog (type Dog) as type Duck }

-

Go's interfaces let you use

duck typinglike you would in a purely dynamic language like Python but still have the compiler catch obvious mistakes like passing anintwhere an object with aReadmethod was expected, or like calling theReadmethod with the wrong number of arguments.

- Let's define another type R that also implements the interface I.

type R struct { i int }

func (p * R) Get() int { return p.i }

func (p *R) Put(v int) { p.i = v }

func f(p I) {

switch t := p.(type) {

case *S:

case *R:

default:

}

}- Create a generic function which has an empty interface as its argument

func g(something interface{}) int {

return something.(I).Get()

}- The

.(I)is a type assertion which convertssomethingto an interface of type I. If we have the type we can invoke theGet()function.

s = new(S)

fmt.Println(g(s))-

Methods are functions that have a receiver.

-

You can definen methods on any type (except on non-local types, this includes built-in types: the type

intcan not have methods). -

Methods on interface types

- An interface defines a set of methods. A method contains the actual code.

- An interface is the definition & the methods are the implementation.

-

By convention, one-method interfaces are named by the method name plus the -er suffix: Reader, Writer, Formatter,...

-

Pointer & Non-pointer method receivers.

func (s *MyStruct) pointerMethod() {} // method on pointer func (s MyStruct) valueMethod() {} // method on value

- When defining a method on a type, the receiver behaves exactly as if it were an argument to the method. Whether to define the receiver as a value or as a pointer is the same question, then, as whether a function argument should be a value or a pointer.

- 1st: Does the method need to modify the receiver? If it does, the receiver must be a pointer (Slices & maps act as references, so their story is a little more subtle, but for instance to change the length of a slice in a method the receiver must still be a pointer). Otherwise, it should be value.

package main import "fmt" type Mutatable struct { a int b int } func (m Mutatable) StayTheSame() { m.a = 5 m.b = 7 } func (m *Mutatable) Mutate() { m.a = 5 m.b = 7 } func main() { m := &Mutatable{0, 0} fmt.Println(m) m.StayTheSame() fmt.Println(m) m.Mutate() fmt.Println(m) }

- 2nd: efficiency. If the receiver is large, a big

structfor instance, it will be much cheaper to use a pointer receiver. - 3rd: consistency. If some of the methods of the type must have pointer receivers, the rest should too, so the method set is consistent regardless of how the type is used.

- For types such as basic types, slices & small

struct, a value receiver is very cheap so unless the semantics of the methods requires a pointer, a value receiver is effient & clear.

- Type switching: A type switching is like a regular switch statement, but the cases in a type switch specify types (not values) which are compared against the type of the value held by the given interface value.

package main

import "fmt"

func do(i interface{}) {

switch v := i.(type) {

case int:

fmt.Printf("Twice %v is %v\n", v, v*2)

case string:

fmt.Printf("%q is %v bytes long\n", v, len(v))

default:

fmt.Printf("I don't know about type %T!\n", v)

}

}

func main() {

do(21)

do("hello")

do(true)

}

// Twice 21 is 42

// "hello" is 5 bytes long

// I don't know about type bool!- More examples here.

- Firstly, don't mess between parallelism & concurrency.

- Goroutines are the central entity in Go's ability for concurrency. A goroutine has a simple model: it is a function executing in parallel with other goroutines in the same address space. It is lightweight, costing little more than the allocation of stack space. And the stack start small, so they are cheap, & grow by allocating (and freeing) heap storage as required.

ready("Tea", 2) // Normal function call

go ready("Tea", 2) // .. Bum! Here is goroutine

/* X ready example */

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func ready(w string, sec int) {

time.Sleep(time.Duration(sec) * time.Second)

fmt.Println(w, "is ready!")

}

func main() {

go ready("Tea", 2) // Tea is ready - After 2 second (3)

go ready("Coffee", 1) // Coffee is ready - After 1 second (2)

fmt.Println("I'm waiting") // Right away (1)

// If did not wait for the goroutines, the program would be terminated

// immediately & any running goroutines would die with it!

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

}- In fact, we have no idea how long we should wait until all goroutine have exited. To fix this, we need some kind of mechanism which allows us to communicate with the goroutines - channel. A channel can be compared to a two-way pipe in Unix shells: you can send to & receive values from it.

/* Define a channel, we must also define the type of

the values we can send on the channel */

ci := make(chan int)

cs := make(chan string)

cf := make(chan interface{})

ci <- 1 // Send the integer 1 to the channel ci

<-ci // Receive an integer from the channel ci

i := <-ci // Receive from the channel ci & store it in i- Put this to previous example (ready).

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

var c chan int

func ready(w string, sec int) {

time.Sleep(time.Duration(sec) * time.Second)

fmt.Println(w, "is ready!")

c <- 1

}

func main() {

c = make(chan int)

go ready("Tea", 2)

go ready("Coffee", 1)

fmt.Println("I'm waiting")

<-c // Wait until we receive a value from the channel

<-c

}-

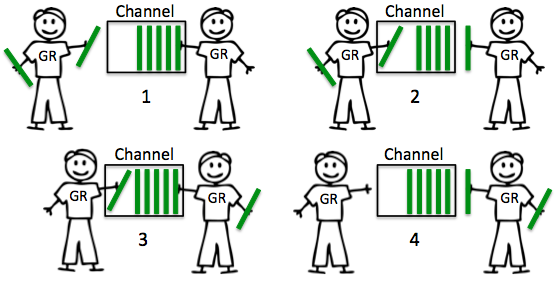

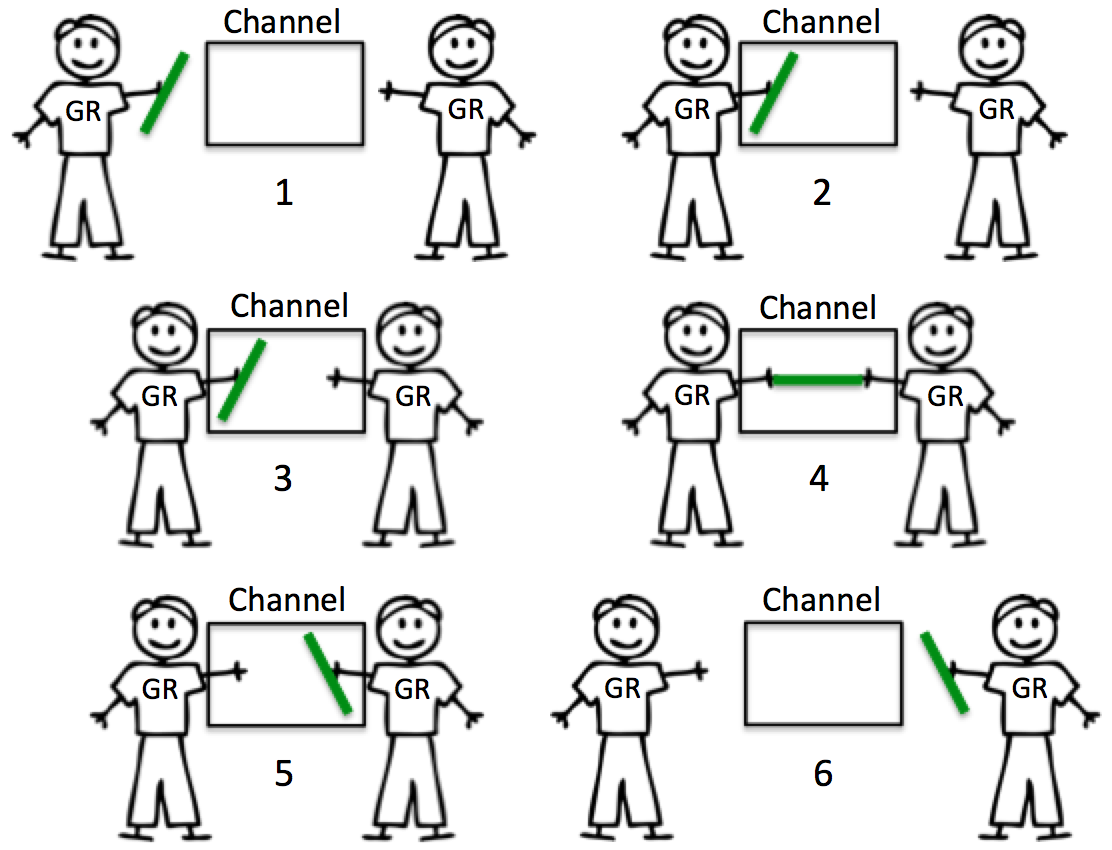

Buffered channel:

-

Buffered channel has capacity.

- When a goroutine attempts to send a resourrce to a buffered and the channel is full, the channel will lock the goroutine and make it wait until a buffer becomes available.

- When a goroutine attempts to receive from a buffered channel and the buffered channel is empty, the channel will lock the goroutine and make it wait until a resource has been sent.

-

Buffered channel is used to perform asynchronous communcation.

-

A buffered channel has no such guarantee.

-

A receive will block only if there's no value in the channel to receive.

-

A send will block only if there's no available buffer to place the value being sent.

-

-

Unbuffered channel:

-

Unbuffered channel has no capacity and therefore require both goroutines to be ready to make any exchange.

- When a goroutine attempts to send a resource to and unbuffered channel and there is no goroutine waiting to receive the resource, the channel will lock the sending goroutine and make it wait.

- When a goroutine attempts to receive from an unbuffered channel, and there is no goroutine waiting to send a resource, the channel will lock the receiving goroutine and make it wait.

-

Unbuffered channel is used to perform synchronous communication between goroutines. Unbuffered channel provides a guarantee that an exchange between 2 goroutines is performed at the instant the send and receive take place.

-

Synchronization is fundamental in the interaction between the send and receive on the channel.

-

unbuffered := make(chan int) // Unbuffered channel of integer type

buffered := make(chan int, 10) // Buffered channel of integer type- You can check ArdanLabs blog post for more detail. These pictures are taken from there.

- What if we don't know how many goroutines we started? This is where another Go built-in comes in:

select.

L: for {

select {

case <-c:

i++

if i > 1 {

break L

}

}

}package main

import "fmt"

func fibonacci(c, quit chan int) {

x, y := 0, 1

for {

select {

case c <- x:

x, y = y, x+y

case <-quit:

fmt.Println("quit")

return

}

}

}

func main() {

c := make(chan int)

quit := make(chan int)

go func() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

quit <- 0

}()

fibonacci(c, quit)

}

// 2

// 3

// 5

// 8

// 13

// 21

// 34

// quit// Default selection

// The default case in a select is run if no other case is ready.

// Use a default case to try a send or receive without blocking:

// select {

// case i := <-c:

// // use i

// default:

// // receiving from c would block

// }

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

tick := time.Tick(100 * time.Millisecond)

boom := time.After(500 * time.Millisecond)

for {

select {

case <-tick:

fmt.Println("tick.")

case <-boom:

fmt.Println("BOOM!")

return

default:

fmt.Println(" .")

time.Sleep(50 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

}-

While our goroutines were running concurrently, they were not running in parallel! (Once more time, make sure you know that Concurrency is not Parralel!)

-

With

runtime.GOMAXPROCS(n)or set an environment variableGOMAXPROCSyou can set the number of goroutines that can run in parallel.- GOMAXPROCS sets the maximum number of CPUs that can be executing simultaneously & returns the previous setting. If n < 1, it does not change the current setting. This call will go away when the scheduler improves.>

-

From version 1.5 & above,

GOMAXPROCSdefaults to the number of CPU cores.

- Note that:

ch := make(chan type, value)

// if value == 0 -> unbuffered

// if value > 0 -> buffer value elements- When a channel is closed the reading side needs to know this

x, ok = <-ch

/* Where ok is set to True the channel is not closed & we've read something

Otherwise ok is set to False. In that case the channel was closed & the value

received is a zero value of the channel's type.- You can find more about concurrency here.

- Building blocks in Go for communcating with the outside world (fiels, directories, networking & executing other programs).

- Central to Go's I/O are the interfaces

io.Reader&io.Writer.

io.Readeris an important interface in the language Go. A lot (if not all) functions that need to read from something take anio.Readeras input.- The writing side

io.Writerhas theWritemethod. - If you think of new type in your program or package & you make it fulfill the

io.Readerorio.Writerinterface, the whole standard Go library can be used on that type.

- Arguments from the command line are available inside your program via the string slide

os.Args. - The

flagpackage has a more sophisticated interface, & also provided a way to parse flags.

- The

os/execpackage has functions to run external commands, & is the premier way to execute commands from within a Go program.

import "os/exec"

cmd := exec.Command("/bin/ls", "-l")

// Just run without doing anything with the returned data

err := cmd.Run()

// Capturing the standard output

buf, err := cmd.Output() // buf is byte slice- All network related types & functions can be found in the package

net. - One of the most important functions in there is

Dial. When youDialinto a remote system the function returns aConninterface type, which can be used to send & receive information. The functionDialneatly abstracts away the network family & transport.

conn, e := Dial("tcp", "192.0.32.10:80")

conn, e := Dial("udp", "192.0.32.10:80")

conn, e := Dial("tcp", "[2620:0:2d0:200::10]:80")Go 1.11 includes preliminary support for modules, Go's new dependency management system that makes dependency version information explicit and easier to manage.

- Modules: a collection of related Go packages that are versioned together as a single unit.

- Summarizing the relationship between repositories, modules, & packages:

- A repository contains one or more Go modules.

- Each module contains one or more Go packages.

- Each package consists of one or more Go source files in a single directory.

- go.mod: A module is defined by a tree of Go source files with a

go.modfile in the tree's root directory. Module source code may be located outside of GOPATH. There are four directives:module,require,replace,exclude. - Version selection: If you add a new import to your source code that is not yet covered by a

requireingo.mod, most go commands like 'go build' & 'go test' will automatically look up the proper module & add the highest version of that new direct dependency to your module'sgo.modas arequiredirective. For example, if your new import corresponds to dependency M whose latest tagged release version isv1.2.3, your module'sgo.modwill end up withrequire M v1.2.3, which indicates module M is a dependency with allowed version >= v1.2.3 (and < v2, given v2 is considered incompatible with v1). - Semantic Import versioning: The result of following both the import compatibility rule & semver is called Semantic Import Versioning, where the major version is included in the import path — this ensures the import path changes any time the major version increments due to a break in compatibility.

- As a result of Semantic Import Versioning, code opting in to Go modules must comply with these rules:

- Follow semver (with tags such as

v1.2.3). - If the module is version v2 or higher, the major version of the module must be included as a

/vNat the end of the module paths used ingo.modfiles (e.g.,module github.com/my/mod/v2,require github.com/my/mod/v2 v2.0.0) & in the package import path (e.g.,import "github.com/my/mod/v2/mypkg"). - If the module is version v0 or v1, do not include the major version in either the module path or the import path.

- Follow semver (with tags such as

- As of Go 1.11, the go command enables the use of modules when the current directory or any parent directory has a

go.mod, provides the directory is outside$GOPATH/src. (Inside$GOPATH/src, for compatibility, the go command still runs in the oldGOPATHmode, even if ago.modis found) - Starting in Go 1.13, module mode will be the default for all development.

- Check Go Modules wiki for updated information.

- Go Module's hello-world: init module and add dependencies.

# Create a directory outside of your GOPATH:

$ mkdir -p /tmp/scratchpad/hello

$ cd /tmp/scratchpad/hello

# Initialize a new module:

$ go mod init github.com/you/hello

go: creating new go.mod: module github.com/you/hello

# Write your code

$ cat <<EOF > hello.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"rsc.io/quote"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(quote.Hello())

}

EOF

# Introduce `go mod tidy`

# Tidy makes sure go.mod matches the source code in the module.

# It adds any missing modules necessary to build the current module's

# packages and dependencies, and it removes unused modules that

# don't provide any relevant packages. It also adds any missing entries

# to go.sum and removes any unnecessary ones

$ go mod tidy t/s/hello ﳑ

go: finding module for package rsc.io/quote

go: downloading rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

go: found rsc.io/quote in rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

go: downloading rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0

go: downloading golang.org/x/text v0.0.0-20170915032832-14c0d48ead0c

$ cat go.mod

module github.com/you/hello

require rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

# Add a new dependency often brings in other indirect dependencies too

# List the current module and all its dependencies

$ go list -m all

github.com/you/hello

golang.org/x/text v0.0.0-20170915032832-14c0d48ead0c

rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0

# In addition to go.mod, there is a go.sum file containing the expected

# cryptographic hashes of the content of specific module versions

$ cat go.sum t/s/hello ﳑ

golang.org/x/text v0.0.0-20170915032832-14c0d48ead0c h1:qgOY6WgZOaTkIIMiVjBQcw93ERBE4m30iBm00nkL0i8=

golang.org/x/text v0.0.0-20170915032832-14c0d48ead0c/go.mod h1:NqM8EUOU14njkJ3fqMW+pc6Ldnwhi/IjpwHt7yyuwOQ=

rsc.io/quote v1.5.2 h1:w5fcysjrx7yqtD/aO+QwRjYZOKnaM9Uh2b40tElTs3Y=

rsc.io/quote v1.5.2/go.mod h1:LzX7hefJvL54yjefDEDHNONDjII0t9xZLPXsUe+TKr0=

rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0 h1:7uVkIFmeBqHfdjD+gZwtXXI+RODJ2Wc4O7MPEh/QiW4=

rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0/go.mod h1:T1hPZKmBbMNahiBKFy5HrXp6adAjACjK9JXDnKaTXpA=

# Build & run

$ go build

$ ./hello

Hello, world.- Upgrade your dependencies:

# From the output of go list -m all, we're using an untagged version of golang.org/x/text

# Let's upgrade to the latest tagged version

$ go get golang.org/x/text t/s/hello ﳑ

go: downloading golang.org/x/text v0.7.0

go: upgraded golang.org/x/text v0.0.0-20170915032832-14c0d48ead0c => v0.7.0

$ cat go.mod t/s/hello ﳑ

module github.com/you/hello

go 1.19

require rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

require (

golang.org/x/text v0.7.0 // indirect

rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0 // indirect

)

$ go list -m all t/s/hello ﳑ

github.com/you/hello

golang.org/x/mod v0.6.0-dev.0.20220419223038-86c51ed26bb4

golang.org/x/sys v0.0.0-20220722155257-8c9f86f7a55f

golang.org/x/text v0.7.0

golang.org/x/tools v0.1.12

rsc.io/quote v1.5.2

rsc.io/sampler v1.3.0- Remove unused dependencies: If you want to remove any dependencies, just simple run

go mod tidyand Go does the rest. - Go modules takes care of versioning, but it doesn't necessarily take care of modules disappearing off the Internet or the Internet not being available. If a module is not available, the code cannot be built. Go Proxy will mitigate disappearing modules to some extent by mirroring modules, but it may not do it for all modules for all time. That's why

gotool providesgo mod vendorcommand.go mod vendorcommand constructs a directory namedvendorin the main module's root directory that contains copies of all packages needed to support builds and tests of packages in the main modules.go mod vendoralso creates the filevendor/modules.txtthat contains a list of vendored packages and the module versions they were copied from.- You can check in

vendorto your Version Control System, then copy this around.

$ go mod vendor

# Main module's directory structure

$ tree -L 3

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── hello.go

└── vendor

├── golang.org

│ └── x

├── modules.txt

└── rsc.io

├── quote

└── sampler- Started from Go 1.13,

gotool defaults to downloading modules from the public Go module mirror: https://proxy.golang.org and also defaults to validating downloaded modules (regardless of source) against the public Go checksum database at https://sum.golang.org. - If you want to change the default Go proxy, you can use the following command:

export GOPROXY=https://goproxy.io,direct- The

gocommand defaults to downloading modules from the public Go module mirror, therefore if you have private code, you most likely should configure theGOPRIVATEsetting (such asgo env -w GOPRIVATE=*.corp.com,github.com/secret/repo), or the more fine-grained variantsGONOPROXYorGONOSUMDBthat support less frequent use cases. See the documentation for more details.

- Go introduces the concept of workspaces in 1.18. Workspaces allows you to create projects of several modules that share a common list of dependencies through a new file called

go.work. The dependencies in this file can span multiple modules and anything declared in thego.workfile will override dependencies in the module'sgo.mod.- A workspace is a collection of modules on disk that are used as the main modules when running minimal version selection (MVS).

- A workspace can be declared in a

go.workfile that specifies relative paths to the module directories of each the modules in the workspace. When nogo.workfile exists, the workspace consists of the single module containing the current directory.- Lexical elements in

go.workfiles are defined in exactly the same way as forgo.modfiles. - Check out here.

- Lexical elements in

go 1.18

use ./my/first/thing

use ./my/second/thing

// or

// use (

// ./my/first/thing

// ./my/second/thing

// )

replace example.com/bad/thing v1.4.5 => example.com/good/thing v1.4.5- Example:

$ mkdir workspace

$ cd workspace

# Create hello module

$ mkdir hello

$ cd hello

$ go mod init eaxmple.com/hello

go: creating new go.mod: module example.com/hello

$ cat <<EOF > hello.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"golang.org/x/example/stringutil"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(stringutil.Reverse("Hello"))

}

EOF

$ go mod tidy

go: finding module for package golang.org/x/example/stringutil

go: found golang.org/x/example/stringutil in golang.org/x/example v0.0.0-20220412213650-2e68773dfca0

$ go run example.com/hello

olleH

# Create the workspace

$ cd ../

$ go work init ./hello

$ tree

.

├── go.work

└── hello

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

└── hello.go

1 directory, 4 files

# Go command includes all the modules in the workspace as main modules. This allow us to refer to a package in the module

# even outside the module.

$ go run example.com/hello

olleH

# Download and modify the golang.org/x/example module

$ git clone https://go.googlesource.com/example

Cloning into 'example'...

remote: Total 165 (delta 27), reused 165 (delta 27)

Receiving objects: 100% (165/165), 434.18 KiB | 1022.00 KiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (27/27), done.

# Add module to the workspace

$ go work use ./example

$ tree -L 1

.

├── example

├── go.work

└── hello

2 directories, 1 file

$ cat go.work

go 1.20

use (

./example

./hello

)

$ cd example/stringutil

# Create a new file

$ cat <<EOF > toupper.go

package stringutil

import "unicode"

// ToUpper uppercases all the runes in its argument string.

func ToUpper(s string) string {

r := []rune(s)

for i := range r {

r[i] = unicode.ToUpper(r[i])

}

return string(r)

}

EOF

# Modify hello program

$ cd ../../hello

$ cat <<EOF > hello.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"golang.org/x/example/stringutil"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(stringutil.ToUpper("Hello"))

}

EOF

$ cd ..

# Go command finds the example.com/hello module specified in the command line

# in the hello directory specified by the go.work file, and similiarly

# resolves the golang.org/x/example import using the go.work file.

$ go run example.com/hello

HELLOSource: https://go.dev/doc/modules/layout

Go projects can include packages, command-line programs or a combination of the two. This guide is organized by project type.

NOTE: throughout this document, file/package names are entirely arbitrary

- A basic Go package has all its code in the project’s root directory. The project consists of a single module, which consists of a single package. The package name matches the last path component of the module name. For a very simple package requiring a single Go file, the project structure is:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

modname.go

modname_test.go

auth.go

auth_test.go

hash.go

hash_test.go- The code in

modname.godeclares the package with:

package modname

// ... package code here- A basic executable program (or command-line tool) is structured according to its complexity and code size. The simplest program can consist of a single Go file where func main is defined. Larger programs can have their code split across multiple files, all declaring package main:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

auth.go

auth_test.go

client.go

main.go- Here the

main.gofile containsfunc main, but this is just a convention. The “main” file can also be calledmodname.go(for an appropriate value of modname) or anything else.

- Larger packages or commands may benefit from splitting off some functionality into supporting packages. Initially, it’s recommended placing such packages into a directory named

internal; this prevents other modules from depending on packages we don’t necessarily want to expose and support for external uses. Since other projects cannot import code from ourinternaldirectory, we’re free to refactor its API and generally move things around without breaking external users. The project structure for a package is thus:

project-root-directory/

internal/

auth/

auth.go

auth_test.go

hash/

hash.go

hash_test.go

go.mod

modname.go

modname_test.go- A module can consist of multiple importable packages; each package has its own directory, and can be structured hierarchically. Here’s a sample project structure:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

modname.go

modname_test.go

auth/

auth.go

auth_test.go

token/

token.go

token_test.go

hash/

hash.go

internal/

trace/

trace.go- As a reminder, we assume that the module line in go.mod says:

module github.com/someuser/modname- Multiple programs in the same repository will typically have separate directories:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

internal/

... shared internal packages

prog1/

main.go

prog2/

main.go- In each directory, the program’s Go files declare package

main. A top-levelinternaldirectory can contain shared packages used by all commands in the repository. - A common convention is placing all commands in a repository into a

cmddirectory; while this isn’t strictly necessary in a repository that consists only of commands, it’s very useful in a mixed repository that has both commands and importable packages, as we will discuss next.

- Sometimes a repository will provide both importable packages and installable commands with related functionality. Here’s a sample project structure for such a repository:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

modname.go

modname_test.go

auth/

auth.go

auth_test.go

internal/

... internal packages

cmd/

prog1/

main.go

prog2/

main.go- Go is a common language choice for implementing servers. There is a very large variance in the structure of such projects, given the many aspects of server development: protocols (REST? gRPC?), deployments, front-end files, containerization, scripts and so on. We will focus our guidance here on the parts of the project written in Go.

- Server projects typically won’t have packages for export, since a server is usually a self-contained binary (or a group of binaries). Therefore, it’s recommended to keep the Go packages implementing the server’s logic in the

internaldirectory. Moreover, since the project is likely to have many other directories with non-Go files, it’s a good idea to keep all Go commands together in a cmd directory:

project-root-directory/

go.mod

internal/

auth/

...

metrics/

...

model/

...

cmd/

api-server/

main.go

metrics-analyzer/

main.go

...

... the project's other directories with non-Go code- In case the server repository grows packages that become useful for sharing with other projects, it’s best to split these off to separate modules.

Go models data input and output as a stream that flows from sources to targets. Data sources, such as files, network connections, or even some in-memory objects , can be modeled as streams of bytes from which data can be read or written to.

The most common usage of the fmt package is for writting to standard output and reading from standard input.

type metalloid struct {

name string

number int32

weight float64

}

func main() {

var metalloids = []metalloid{

{"Boron", 5, 10.81},

...

{"Polonium", 84, 209.0},

}

file, _ := os.Create("./metalloids.txt")

defer file.Close()

for _, m := range metalloids {

fmt.Fprintf(

file,

"%-10s %-10d %-10.3f\n",

m.name, m.number, m.weight,

)

}

}The bufio package offers several functions to do buffered writing of IO streams using an `io.Writer interface.

In bytes package offers common primitives to achieve streaming IO on blocks of bytes stored in memory, represented by the bytes.Buffer byte. Since the bytes.Buffer type implements both io.Reader and io.Writer interfaces it is a great option to stream data into or out of memory using streaming IO primitives.

- Go’s standard library comes packed with some great encoding and decoding packages covering a wide array of encoding schemes. Everything from CSV, XML, JSON, and even gob - a Go specific encoding format - is covered, and all of these packages are incredibly easy to get started with.

- Go offers built-in support for JSON encoding and decoding, including to and from built-in and custom data types.

- There are two types of data:

- Structured data

- Unstructured data

- Marshal and Unmarshal Structured data (Decoding JSON into structs)

- json package will assign values only to fields found in the JSON; other fields will just keep their Go zero values.

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

type Measurement struct {

Height int

Weight int

}

type Person struct {

Name string

Age int

Measurement Measurement // Nested object

}

func main() {

bob := &Person{

Name: "Bob",

Age: 20,

}

bobRaw, _ := json.Marshal(bob)

fmt.Println(string(bobRaw))

// Raw data without Measurement field

aliceRaw := []byte(`{"name": "Alice", "age": 23}`)

var alice Person

if err := json.Unmarshal(aliceRaw, &alice); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", alice)

}

// {"Name":"Bob","Age":20,"Measurement":{"Height":190,"Weight":75}}

// {Name:Alice Age:23 Measurement:{Height:0 Weight:0}}- JSON struct tags - custom field names: Somtimes we want a different attribute name than the one provided in your JSON data.

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

type Measurement struct {

Height int `json:"height"`

Weight int `json:"weight"`

}

type Person struct {

Name string `json:"who"`

Age int `json:"how old"`

Measurement Measurement `json:"mm"`

}

func main() {

bob := &Person{

Name: "Bob",

Age: 20,

}

bobRaw, _ := json.Marshal(bob)

fmt.Println(string(bobRaw))

// Raw data without Measurement field

aliceRaw := []byte(`{"who": "Alice", "how old": 23, "mm": {"height": 150, "weight": 40}}`)

var alice Person

if err := json.Unmarshal(aliceRaw, &alice); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Printf("%+v", alice)

}

// {"who":"Bob","how old":20,"mm":{"height":0,"weight":0}}

// {Name:Alice Age:23 Measurement:{Height:150 Weight:40}}- Decoding JSON to Maps - Unstructured Data

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

// Raw data without Measurement field

aliceRaw := []byte(`{"name": "Alice", "age": 23, "measurement": {"height": 150, "weight": 40}}`)

var alice map[string]interface{}

if err := json.Unmarshal(aliceRaw, &alice); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// the object stored in the "mesurement" key is also stored

// as a map[string]interface{} type, and its type is asserted

// the interface{} type

measurement := alice["measurement"].(map[string]interface{})

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", alice)

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", measurement)

}

// map[age:23 measurement:map[height:150 weight:40] name:Alice]

// map[height:150 weight:40]- Ignore empty fields: In some cases, we would want to ignore a field in our JSON output, if its value is empty. We can use the

omitemptyproperty.

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

type Measurement struct {

Height int `json:"height"`

Weight int `json:"weight"`

}

type Person struct {

Name string `json:"name"`

Age int `json:"age,omitempty"`

Measurement Measurement `json:"measurement"`

}

func main() {

bob := &Person{

Name: "Bob",

Measurement: Measurement{

Height: 190,

Weight: 75,

},

}

bobRaw, _ := json.Marshal(bob)

fmt.Println(string(bobRaw))

}

// Age field is ignored

// {"name":"Bob","measurement":{"height":190,"weight":75}}- About the Advanced Encoding and Decoding techniques, you can check this blog.

NOTE: There are a lot more helpful things in tips-notes. You may want to check it out.

A basic HTTP server has a few key jobs to take care of:

- Process dynamic request: Process incoming requests from users who browse the website, log into their accounts or post images.

- Serve static assets: Serve JavaScript, CSS & images to browsers to create a dynamic experience for the user.

- Accept connections: The HTTP Server must listen on a specific port to be able to accept connections from the Internet.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

// Process dynamic request

http.HandleFunc("/", func (w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Welcome to my website!")

})

// Serving static assets

fs := http.FileServer(http.Dir("static/"))

http.Handle("/static/", http.StripPrefix("/static/", fs))

// Accept connections

http.ListenAndServe(":80", nil)

}A simple logging middleware.

// basic-middleware.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

)

func logging(f http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

log.Println(r.URL.Path)

f(w, r)

}

}

func foo(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintln(w, "foo")

}

func bar(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintln(w, "bar")

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/foo", logging(foo))

http.HandleFunc("/bar", logging(bar))

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}-

A middleware in itself simple takes a

http.HandleFuncas one of its parameters, wraps it & returns a newhttp.HandlerFuncfor the server to call. -

Define a new type

Middlewarewhich makes it eventually easier to chain multiple middlewares together. -

How a new middleware is created, boilerplate code:

func newMiddleware() Middleware {

// Create a new Middleware

middleware := func(next http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

// Define the http.HandlerFunc which is called by the server eventually

handler := func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// ... do middleware things

// Call the next middleware/handler in chain

next(w, r)

}

// Return newly created handler

return handler

}

// Return newly created middleware

return middleware

}- Show me code! Ok, a full example is here:

// advanced-middleware.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"time"

)

type Middleware func(http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc

// Logging logs all requests with its path & the time it took to process

func Logging() Middleware {

// Create a new Middleware

return func(f http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

// Define the http.HandlerFunc

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Do middleware things

start := time.Now()

defer func() { log.Println(r.URL.Path, time.Since(start)) }()

// Call the next middleware/handler in chain

f(w, r)

}

}

}