Up To Schedule - Back To Write Code for People - Forward to Make Incremental Changes

Based on Lecture Materials By: Milad Fatenejad and Katy Huff

We will continue with one of the most important principles of programming: "Don't repeat yourself". We will see how instead of copying and pasting statements with slight modifications we can use loops. Adding conditionals allows a loop to do slightly different things each time. Then we will learn how functions allow us to pack sections of code into reusable parts. Finally, we'll see how to use modules that are a collection of related functions and how to make our modules so we can reuse functions across different projects. We will finish with a lot of interesting and sometime challenging examples and exercises.

This part of the lesson includes a lot of text, but it will be useful to run it yourself in iPython.

To paste text from another application (i.e. these lecture notes) into iPython :

- select text from the wiki

- copy with Ctrl+c (or ⌘+c on Mac OSX)

- unfortunately pasting depends on your operating system and ssh program:

Click with the right mouse button over the window.

##### Bitvise SSH Click with the right mouse button over the window and then "Paste".

#### Mac OSX Press ⌘+v.

Click with the right mouse button over the window and then "Paste".

The code should paste and execute in iPython.

If you also type %autocall to turn autocall OFF, you may be able to paste with Ctrl+v though this won't work with all iPython builds.

Another helpful strategy will be to paste this content into a separate file and then run that file. It is generally easiest to do this with multiple terminal windows.

For loops in python operate a little differently from other languages.

Let's start with a simple example which prints all of the numbers from 0

to 9:

for i in range(10):

print i

print "That's all"You may be wondering how this works. Start by using help(range) to see

what the range function does.

range()?

Help on built-in function range in module __builtin__:

range(...)

range([start,] stop[, step]) -> list of integers

Return a list containing an arithmetic progression of integers.

range(i, j) returns [i, i+1, i+2, ..., j-1]; start (!) defaults to 0.

When step is given, it specifies the increment (or decrement).

For example, range(4) returns [0, 1, 2, 3]. The end point is omitted!

These are exactly the valid indices for a list of 4 elements.

Range is a function that returns a list containing a sequence of

integers. So, range(10) returns the list [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The for

loop then simply iterates over that list, setting i to each value.

Other than the range function, the behavior of this code snippet should be

pretty clear, but there is something peculiar. How does Python know where the

for loop ends? Why doesn't it print "That's all" 10 times? Other

languages, like FORTRAN, MatLab, and C/C++ all have some way of delimiting

blocks of code.

For example, in MatLab you begin an for loop with the word for

and you end it with end. In C/C++ you delimit code blocks with curly

braces.

Python uses white space — in this case, indentation, to group lines of

code. In this case, there are four spaces at the beginning of the line

following the for statement. This is not just to make things look pretty - it

tells Python what the body of the for-loop is.

Marking blocks of code is a fundamental part of a language. In C, you'll see curly braces everywhere. In Python, you'll see indentation everywhere. It's how you (and the computer) know what your code means.

White space and indentation are important to make code readable by people. In

most languages indentation is optional and often results in poor habits.

Since it is required in python, this readability imposted by the language

itself. Little things like putting blank lines in "sane" places, and putting

spaces between variables and operators (say, a + b rather than a+b) can

also make your code a lot easier to read.

Using a loop, calculate the factorial of 6 (the product of all positive integers up to and including 6).

With range, we learned that for loops in python are really used to

iterate over sequences of things (they can be used for much more, but

for now this definition will do). Try entering the following to see what

happens:

for c in ["one", 2, "three", 4, "five"]:

print cthis is equivalent to:

c = ["one", 2, "three", 4, "five"]

for i in range(len(c)):

print c[i]However, notice how much more readable the first one is!

With a list, then, it's clear that we can use the in keyword to

indicate a list of things. What about a nested loops around a list of

lists?

italy_cities = ["Rome", "Pisa", "Florence", "Venice", "Trieste"]

argentina_cities = ["Mendoza", "Buenos Aires", "Patagonia"]

india_cities = ["Ahmedabad", "Kolkata", "Chennai", "Jaipur", "Surat"]

us_cities = ["Chicago", "Austin", "New York", "San Fran"]

all_cities = [italy_cities, argentina_cities, india_cities, us_cities]

nationnames = ["italy", "argentina", "india", "us"]

for cities in all_cities :

print nationnames[all_cities.index(cities)] + ": "

for city in cities :

print " " + city Can you think of a better use of compound data types for this example?

Of course, this information is better stored in a dictionary, isn't it? The data makes more sense if the keys were the nation names and the values were lists of cities. Importantly, python has given us a tool specifically for dictionary looping.

The syntax for looping through the keys and values of a dictionary is :

for key, value in dictionary.iteritems():

Importantly, you don't have to use the words key and value. That's just what will fill those variables. Here, we rewrite the previous loop using this clever syntax.

all_cities = {} # make an empty dictionary

all_cities['italy'] = ["Rome", "Pisa", "Florence", "Venice", "Trieste"]

all_cities['argentina'] = ["Mendoza", "Buenos Aires", "Patagonia"]

all_cities['india'] = ["Ahmedabad", "Kolkata", "Chennai", "Jaipur", "Surat"]

all_cities['us'] = ["Chicago", "Austin", "New York", "San Fran"]

for nation, cities in all_cities.iteritems() :

print nation + " : "

for city in cities :

print " " + city So far our loops always do the same thing each time we pass through, but often that is not the case. There is often a condition we would like to check, and then have some different behavior.

A conditional (if statement) is some statement that in general says : "When

some boolean is true, do the following. Elsewise, do this other thing."

Many equivalence test statements exist in Python that are similar in other languages:

i = 1

j = 2

i == j # i is equal to j : False

i < j # i is less than j : True

i <= j # i is less than or equal to j : True

i > j # i is greater than j : False

i >= j # i is greater than or equal to j : False

i != j # i is not equal to j : TrueHowever, python has other equivalence test statements that are fairly unique to python. To check whether an object is contained in a list :

beatle = "John"

beatles = ["George", "Ringo", "John", "Paul"]

print(beatle in beatles) # is John one of the beatles? : TRUE

print("Katy" not in beatles) # this is also TRUE. Conditionals (if statements) are also really easy to use in python. Take

a look at the following example:

i = 4

sign = "zero"

if i < 0:

sign = "negative"

elif i > 0:

sign = "positive"

else:

print("Sign must be zero")

print("Have a nice day")

print(sign)Write an if statement that prints whether x is even or odd.

Hint: Try out what the "%" operator. What does 10 % 5 and 10 % 6 return?

A break statement cuts off a loop from within an inner loop. It helps

avoid infinite loops by cutting off loops when they're clearly going

nowhere.

dont_print = 5

for n in range(1,10):

if n == dont_print :

break

print nSomething you might want to do instead of breaking is to continue to the next iteration of a loop, giving up on the current one..

dont_print = 5

for n in range(1,10):

if n == dont_print :

continue

print nWhat is the difference between the output of these two?

We can combine loops and flow control to take actions that are more complex, and that depend on the data. First, let us define a dictionary with some names and titles, and a list with a subset of the names we will treat differently.

knights = {"Sir Belvedere":"the Wise",

"Sir Lancelot":"the Brave",

"Sir Galahad":"the Pure",

"Sir Robin":"the Brave",

"The Black Knight":"John Cleese"} # create a dict with names and titles

favorites = knights.keys() # create a list of favorites with all the knights

favorites.remove("Sir Robin") # change favorites to include all but one.

print knights

print favoritesWe can loop through the dictionary of names and titles and do one of

two different things for each by putting an if statement inside

the for loop:

for name, title in knights.items():

string = name + ", "

if name in favorites: # this returns True if any of the values in favorites match.

string = string + title

else:

string = string + title + ", but not quite so brave as Sir Lancelot."

print string###enumerate###

Python lists and dictionaries can easily be iterated through in a for loop by using in. As we saw above, this is clearer than writing a for loop over the integers up to the length of the list (or dictionary, or other iterable). However, sometimes you may need the index value at the same time, for example for some calculation. The enumerate function generates the integer index for you, which can be used instead of the range function. The following two loops are equivalent:

data_list = [23,45,67]

for i in range(len(data_list)):

print data_list[i], ' is item number ', i, ' in the list'

for i,d in enumerate(data_list):

print d, ' is item number ', i, ' in the list'We've seen a lot so far. Let's work through a slightly lengthier example

together. I'll use some of the concepts we already saw and introduce a

few new concepts. To run the example, you'll need to locate a short file

containing phone numbers. The file can be found in your

repository within the phonenums directory and is called phonenums.txt.

Now we have to move iPython to that directory so it can find the

phonenums.txt file. You navigate within iPython in the same way that you

navigate in the shell, by entering "cd [path]" .

Let's look at the phonenums.txt file. We can type shell commands into

iPython by prefacing them with '!', e.g. !nano phonenums.txt

Let's use a simple loop on the file:

f = open("phonenums.txt") # Open the text file

for line in f: # iterate through the text file, one line at a time

print lineWe see a list of phonenumbers. We want to count how many are in each areacode.

This example opens a text file containing a list of phone numbers. The phone numbers are in the format ###-###-####, one to a line.

Now let's write some code that loops through each line in the file and counts the number of times each area code appears. The answer is stored in a dictionary, where the area code is the key and the number of times it occurs is the value.

areacodes = {} # Create an empty dictionary

f = open("phonenums.txt") # Open the text file

for line in f: # iterate through the text file, one line at a time (think of the file as a list of lines)

ac = line.split('-')[0] # Split phone number, first element is the area code

if not ac in areacodes: # Check if it is already in the dictionary

areacodes[ac] = 1 # If not, add it to the dictionary

else:

areacodes[ac] += 1 # Add one to the dictionary entry

print areacodes # Print the answerUse a loop to print the area codes and number of occurences in one line.

Remember how we previously looped through a dictionary using iteritems.

Your output should look like this:

203 4

800 4

608 8

773 3

One feature of a for loop is that you need to know exactly how many times

you'll go through the loop before you begin. Often, we'd like to keep looping

until some condition changes, but we don't know a priori how many iterations

that will take. For this we have the while loop.

They function like while loops in many other languages. The example below takes a list of integers and computes the product of each number in the list up to the -1 element.

A while loop will repeat the instructions within itself until the

conditional that defines it is no longer true.

mult = 1

sequence = [1, 5, 7, 9, 3, -1, 5, 3]

while sequence[0] != -1:

mult = mult * sequence[0]

sequence.pop(0)

print multSome new syntax has been introduced in this example.

-

On line 4, we compute the product of the elements just to make this more interesting.

-

On line 5, we use list.pop() to remove the first element of the list, shifting every element down one. Let's verify this with sequence.pop?

Watch Out

Since a while loop will continue until its conditional is no longer true, a

poorly formed while loop might repeat forever. If this happens, you can

interrupt it with Ctrl+C (or ⌘+C

on Mac OSX).

For example :

i=1

print "Well, there's egg and bacon, egg and spam, egg bacon and"

while i == 1:

print "spam "

print "or Lobster Thermidor a Crevette with a mornay sauce served in a Provencale manner with shallots..."Since the variable i never changes within the while loop, we can

expect that the conditional, i=1 will remain true forever and the

while loop will just go round and round, as if this restaurant offered

nothing but spam.

In general, the logic for finishing a while loop at the right time can be more challenging that just counting the number of elements in a list for a for loop. Be careful to test your code carefully to make sure that it is ending when you want it to, and not too early or too late. Being off by just one iteration of the loop is a common mistake and can be hard to debug.

A function is a block of code that performs a specific task. In this section we will learn how to utilize available Python functions as well as write our own. The topics in this section are:

- Python methods for strings

- Writing our own functions

- Importing Python modules

As you saw in the last lesson, computers are very useful for doing the same

operation over and over. When you know you will be performing the same

operation many times, it is best to abstract this functionality into a

function (aka method). For example, you used the function open in an earlier

section. This allowed you to easily open a connection to a file without

worrying about the underlying code that made it possible (this idea is known

as abstraction).

##Built-in string methods##

The base distribution comes with many useful functions. When a function works on a specific type of data (lists, strings, dictionaries, etc.), it is called a method. I will cover some of the basic string methods since they are very useful for reading data into Python.

# Find the start codon of a gene

dna = 'CTGTTGACATGCATTCACGCTACGCTAGCT'

start_codon = 'ATG'

dna.find(start_codon)

# parsing a line from a comma-delimted file

lotto_numbers = '4,8,15,16,23,42\n'

lotto_numbers.strip().split(',')

question = '%H%ow%z%d%@d%z%th%ez$%@p%ste%rzb%ur%nz%$%@szt%on%gue%?%'

print question.replace('%', '').replace('@', 'i').replace('$', 'h').replace('z', ' ')

answer = '=H=&!dr=a=nk!c=~ff&&!be=f~r&=!i=t!w=as!c=~~l.='

print answer.replace('=', '').replace('&', 'e').replace('~', 'o').replace('!', ' ') Exercise: Calculate GC content of DNA

Exercise: Calculate GC content of DNA

Because the binding strength of guanine (G) to cytosine (C) is different from the binding strength of adenine (A) to thymine (T) (and many other differences), it is often useful to know the fraction of a DNA sequence that is G's or C's. Go to the string method section of the Python documentation and find the string method that will allow you to calculate this fraction.

# Calculate the fraction of G's and C's in this DNA sequence

seq1 = 'ACGTACGTAGCTAGTAGCTACGTAGCTACGTA'

gc = Check your work:

round(gc, ndigits = 2) == .47##Creating your own functions!##

When there is not an available function to perform a task, you can write your own functions. There are a number of reasons to write functions to accomplish a given task:

- keep the cognitive burden low by only requiring the reader to process a small amount of code at a time

- perform the task in multiple places without cutting and pasting

- ensure that the task is performed the same way in all of those places

- enable testing (coming tomorrow) of small units of your code

def square(x):

return x * x

print square(2), square(square(2))

def hello(time, name):

"""Print a nice message. Time and name should both be strings.

Example: hello('morning', 'Software Carpentry')

"""

print 'Good ' + time + ', ' + name + '!'

hello('afternoon', 'Software Carpentry')The description right below the function name is called a docstring. For best practices on composing docstrings, read PEP 257 -- Docstring Conventions.

Also remember that the same best practices that apply to naming variables apply to function names. Make them meaningful. Some style guides suggest that function names should always be verbs and variable names should always be nouns.

Short exercise: Write a function to calculate GC content of DNA

Short exercise: Write a function to calculate GC content of DNA

Make a function that calculate the GC content of a given DNA sequence. For the more advanced participants, make your function able to handle sequences of mixed case (see the third test case).

def calculate_gc(x):

"""Calculates the GC content of DNA sequence x.

x: a string composed only of A's, T's, G's, and C's."""Check your work:

print round(calculate_gc('ATGC'), ndigits = 2) == 0.50

print round(calculate_gc('AGCGTCGTCAGTCGT'), ndigits = 2) == 0.60

print round(calculate_gc('ATaGtTCaAGcTCgATtGaATaGgTAaCt'), ndigits = 2) == 0.34##Modules##

Python has a lot of useful data type and functions built into the language, some of which you have already seen. For a full list, you can type dir(__builtins__). However, there are even more functions stored in modules. An example is the sine function, which is stored in the math module. In order to access mathematical functions, like sin, we need to import the math module. Let's take a look at a simple example:

print sin(3) # Error! Python doesn't know what sin is...yet

import math # Import the math module

math.sin(3)

print dir(math) # See a list of everything in the math module

help(math) # Get help information for the math moduleIt is not very difficult to use modules - you just have to know the module name and import it. There are a few variations on the import statement that can be used to make your life easier. Let's take a look at an example:

from math import * # import everything from math into the global namespace (A BAD IDEA IN GENERAL)

print sin(3) # notice that we don't need to type math.sin anymore

print tan(3) # the tangent function was also in math, so we can use that tooreset # Clear everything from IPython

from math import sin # Import just sin from the math module. This is a good idea.

print sin(3) # We can use sin because we just imported it

print tan(3) # Error: We only imported sin - not tanreset # Clear everything

import math as m # Same as import math, except we are renaming the module m

print m.sin(3) # This is really handy if you have module names that are longThe main reason for these different variations is to allow you to find a balance between convenience and so-called name collisions.

The strictest form is the last one (import math as m). It ensures that the functions imported from math never collide with others, but requires you to type m. before every one when you use it. Some also see it as a benefit to be constantly reminded which module the function came from by this m.

Slightly less strict is the second one (from math import sin). It saves the trouble of typing the m. each time but adds the risk that you import something that overwrites another method of the same name. The risk is mitigated by only importing those things that you need, but requires you to think of this ahead of time.

The laziest form is the first one (from math import *). It allows you to use any function from the math without thinking of all the things you need. However, this gives the maximum risk of having functions that collide with functions from other modules.

If you intend to use python in your workflow, it is a good idea to skim the standard library documentation at the main Python documentation site, docs.python.org to get a general idea of the capabilities of python "out of the box".

Let's take a look at some nice docstrings:

import numpy

numpy.sum??

Type: function

String Form:<function sum at 0x0000000002D1C5F8>

File: c:\anaconda\lib\site-packages\numpy\core\fromnumeric.py

Definition: numpy.sum(a, axis=None, dtype=None, out=None, keepdims=False)

Source:

def sum(a, axis=None, dtype=None, out=None, keepdims=False):

"""

Sum of array elements over a given axis.

Parameters

----------

a : array_like

Elements to sum.

axis : None or int or tuple of ints, optional

Axis or axes along which a sum is performed.

The default (`axis` = `None`) is perform a sum over all

the dimensions of the input array. `axis` may be negative, in

which case it counts from the last to the first axis.

.. versionadded:: 1.7.0

If this is a tuple of ints, a sum is performed on multiple

axes, instead of a single axis or all the axes as before.

dtype : dtype, optional

The type of the returned array and of the accumulator in which

the elements are summed. By default, the dtype of `a` is used.

An exception is when `a` has an integer type with less precision

than the default platform integer. In that case, the default

platform integer is used instead.

out : ndarray, optional

Array into which the output is placed. By default, a new array is

created. If `out` is given, it must be of the appropriate shape

(the shape of `a` with `axis` removed, i.e.,

``numpy.delete(a.shape, axis)``). Its type is preserved. See

`doc.ufuncs` (Section "Output arguments") for more details.

keepdims : bool, optional

If this is set to True, the axes which are reduced are left

in the result as dimensions with size one. With this option,

the result will broadcast correctly against the original `arr`.

Returns

-------

sum_along_axis : ndarray

An array with the same shape as `a`, with the specified

axis removed. If `a` is a 0-d array, or if `axis` is None, a scalar

is returned. If an output array is specified, a reference to

`out` is returned.

See Also

--------

ndarray.sum : Equivalent method.

cumsum : Cumulative sum of array elements.

trapz : Integration of array values using the composite trapezoidal rule.

mean, average

Notes

-----

Arithmetic is modular when using integer types, and no error is

raised on overflow.

Examples

--------

>>> np.sum([0.5, 1.5])

2.0

>>> np.sum([0.5, 0.7, 0.2, 1.5], dtype=np.int32)

1

>>> np.sum([[0, 1], [0, 5]])

6

>>> np.sum([[0, 1], [0, 5]], axis=0)

array([0, 6])

>>> np.sum([[0, 1], [0, 5]], axis=1)

array([1, 5])

If the accumulator is too small, overflow occurs:

>>> np.ones(128, dtype=np.int8).sum(dtype=np.int8)

-128

"""We see a nice docstring seperating into several sections. A short description of the function is given, then all the input parameters are listed, then the outputs, there are some notes and examples. Please note the docstring is longer than the code. And there are few comments in the actual code.

We have written a number of short functions. Collect these in a text file with an extension ".py", for example, "myFunctions.py". Test out the different import methods listed above. You may want to reset the iPython session between imports in the same way as the examples.

Try adding a new function to the module. Note that you need to reload the module in python to update it, if the module is already imported. For example:

import myFunctions as myFun

# ... editing myFunctions.py in nano or other text editor...

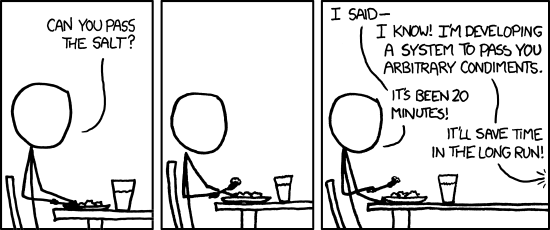

reload(myFun)##The General Problem##

From xkcd

Now that you can write your own functions, you too will experience the dilemma of deciding whether to spend the extra time to make your code more general, and therefore more easily reused in the future.

Short exercise: Write a function to calculate content fraction of DNA

Short exercise: Write a function to calculate content fraction of DNA

One common pattern is to generalize an existing function to work over a wider class of inputs. Try this by generalizing the calculate_gc function above to a new function, calculate_dna_fraction that computes the fraction for an arbitrary list of DNA bases. Add this to your own module file. Remember to reload the module after adding or modifying the python file. (This function will be more complicated than previous functions, so writing it interactively within iPython will not work as well.)

def calculate_dna_fraction(x, bases):

"""Calculate the fraction of DNA sequence x, for a set of input bases.

x: a string composed only of A's, T's, G's, and C's.

bases: a string containing the bases of interest (A, T, G, C, or

some combination)"""Check your work. Note that since this is a generalization of calculate_gc, it should reproduce the same results as that function with the proper input:

test_x = 'AGCGTCGTCAGTCGT'

print calculate_gc(test_x) == calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, 'GC')

print round(calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, 'C'), ndigits = 2) == 0.27

print round(calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, 'TGC'), ndigits = 2) == 0.87Generalization can bring problems, due to "corner cases", and unexpected inputs. You need to keep these in mind while writing the function; this is also where you should think about test cases. For example, what should the results from these calls be?

print calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, 'AA')

print calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, '')

print calculate_dna_fraction(test_x, 2.0)##Longer exercise: Reading Cochlear implant into Python##

For this exercise we will return to the cochlear implant data first introduced in the section on the shell. In order to analyse the data, we need to import the data into Python. Furthermore, since this is something that would have to be done many times, we will write a function to do this. As before, beginners should aim to complete Part 1 and more advanced participants should try to complete Part 2 and Part 3 as well.

###Part 1: View the contents of the file from within Python###

Write a function view_cochlear that will open the file and print out each line. The only input to the function should be the name of the file as a string.

def view_cochlear(filename):

"""Write your docstring here.

"""Test it out:

view_cochlear('/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/alexander/data_216.DATA')

view_cochlear('/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/Lawrence/Data0525')###Part 2:###

Adapt your function above to exclude the first line using the flow control techniques we learned in the last lesson. The first line is just # (but don't forget to remove the '\n').

def view_cochlear(filename):

"""Write your docstring here.

"""Test it out:

view_cochlear('/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/alexander/data_216.DATA')

view_cochlear('/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/Lawrence/Data0525')###Part 3:###

Adapt your function above to return a dictionary containing the contents of the file. Split each line of the file by a colon followed by a space (': '). The first half of the string should be the key of the dictionary, and the second half should be the value of the dictionary.

def load_cochlear(filename):

"""Write your docstring here.

"""Check your work:

data_216 = load_cochlear("/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/alexander/data_216.DATA")

print data_216["Subject"]

Data0525 = load_cochlear("/home/<username>/boot-camps/shell/data/Lawrence/Data0525")

print Data0525["CI type"]##Bonus Exercise: Transcribe DNA to RNA##

###Motivation:###

During transcription, an enzyme called RNA Polymerase reads the DNA sequence and creates a complementary RNA sequence. Furthermore, RNA has the nucleotide uracil (U) instead of thymine (T).

###Task:###

Write a function that mimics transcription. The input argument is a string that contains the letters A, T, G, and C. Create a new string following these rules:

- Convert A to U

- Convert T to A

- Convert G to C

- Convert C to G

Hint: You can iterate through a string using a for loop similarly to how you loop through a list.

def transcribe(seq):

"""Write your docstring here.

"""Check your work:

transcribe('ATGC') == 'UACG'

transcribe('ATGCAGTCAGTGCAGTCAGT') == 'UACGUCAGUCACGUCAGUCA'Up To Schedule - Back To Write Code for People - Forward to Make Incremental Changes